The Copyright Act gives a great deal of power to the original creators of works. For works created after 1977, the original author of a work can terminate any grant of rights roughly between 35 and 40 years after the date of the grant and provided that at least two years’ notice of the termination has been given. The right of termination cannot be forfeited: “Termination of the grant may be effected notwithstanding any agreement to the contrary.”

The termination right was in recognition of the imbalance of power between a creator and an intermediary that commercializes the work. It gives creators a second opportunity to negotiate the terms for exploitation of their work after the creator becomes more well-known. However, the right can become disproportionally coercive when the copyrighted work is also a trademark.

The Phillies v. Harrison/Erickson is a master class in exercising the termination right for maximum exploitation of a work. In March 1978, defendants Bonnie Erickson and Wayde Harrison d/b/a Harrison/Erickson (“H/E”) entered into an agreement with The Phillies to create a mascot for the team, the “Phillie Phanatic.” The agreement said that H/E would own the copyright and license it to The Phillies. A later agreement in July 1978 also licensed the copyright. H/E registered the copyright in the design.

Within a year H/E sued The Phillies in the Southern District of New York for breach of the license and settled the claim in November 1979. On October 31, 1984, H/E assigned the copyright to the Phillies, “everywhere and forever.” H/E continued to do work for The Phillies; between the assignment and the subsequent work H/E performed, The Phillies paid H/E about $1 million.

On June 1, 2018 H/E sent a termination notice to The Phillies, notifying The Phillies that it was terminating the 1984 assignment effective June 15, 2020. Shortly thereafter a lawsuit ensued, with multiple attacks and counterattacks by both parties.

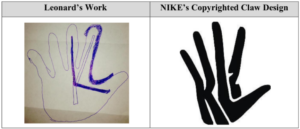

The Phillies was not entirely at the mercy of H/E though. Section 203 provides that “A derivative work prepared under authority of the grant before its termination may continue to be utilized under the terms of the grant after its termination . …” Upon receiving the termination notice, The Phillies set about creating a derivative work of the original Phillie Phanatic, shown below (original on the left, new design on the right):

The Phillies debuted the new Phillie Phanatic, “P2,” in February 2020 at spring training.

Although The Phillies floated a number of different long-shot theories in its defense, whether P2 was a derivative work was “the heart of this case.” If it was, The Phillies could continue to use P2 as the mascot. If not, then H/E could successful extract even more rents from the work it did on the original mascot.

In deciding whether P2 was a derivative work, the magistrate made a helpful point:

Derivative works “make[] non-trivial contributions to an existing” work and “retain[] the ‘same aesthetic appeal’ as the original work, [which] render the holder liable for infringement of the original copyright if the derivative work were to be published without permission from the owner of the original copyright.” Eden Toys, Inc. v. Florelee Undergarment Co., 697 F.2d 27, 34 (2d Cir. 1982) (emphasis added) (the “Paddington Bear case”) …

…

H/E argue that P2 is not original because it is the “same old Phanatic” or a “slavish copy” of P1. But a derivative work is supposed to “retain[] the ‘same aesthetic appeal’ as the original work.” Id. at 34. Indeed, if the derivative work of Paddington Bear was not recognizable as Paddington Bear, then it would not be derivative – it would be an entirely new creation. If The Phillies had designed something so dissimilar from the Phanatic that it would no longer be recognizable as the Phanatic, then, by extension, it would not be a derivative of the Phanatic, and instead would be a completely different mascot. To be sure, the changes to the structural shape of the Phanatic are no great strokes of brilliance, but as the Supreme Court has already noted, a compilation of minimally creative elements, “no matter how crude, humble or obvious,” can render a work a derivative. Feist Publ’ns, 499 U.S. at 345.

Thus, The Phillies was successful in its claim that P2 was a lawful derivative work that it could continue to use post-termination. Nevertheless, while a legal victory, the success has limited business value. P2 was an authorized derivative work, but nothing created after termination, including all of the fan merchandise, would be a lawful derivative work. The Phillies would be locked in to the rights it had established before termination and couldn’t expand.

But the parties have settled. The consent judgment states that P2 was a derivative work according to the terms of the 1984 agreement and can continue to be used “even if one or more of the provisions of the Confidential Settlement Agreement and Assignment are invalidated or terminated.” And according to news reports, The Phillies will resume use of the original Phanatic, presumably an agreement reached in the Confidential Settlement Agreement, also presumably with another payment to H/E.

There were also some interesting claims at the intersection of copyright and trademark, but the magistrate was able to recommend dismissing them without any substantive analysis. H/E had threatened to license the Phillie Phanatic to other teams, so The Phillies brought a declaratory judgment action for trademark infringement. The magistrate found that there was not a controversy of sufficient immediacy and reality that The Phillies had standing for declaratory judgment, so dismissed the claim. There is nevertheless a lesson that a copyright owner terminating the rights in a work also used as trademark may not to have a resale market for their work.

The Phillies also brought state law claims for unjust enrichment and for breach of the covenant of good faith and fair dealing. The Phillies claim for unjust enrichment was premised on the theory that it paid $215,000 in 1984 for a term of “forever”; thus the termination would be an unjust enrichment. H/E argued that the 1984 agreement implicitly contained an unqualified termination of rights. Summary judgment was denied since it is a question of fact. I hope The Phillies’ theory isn’t right; if not, then an unjust enrichment claim can be used to subvert the intention in the Copyright Act that an author will have an inalienable right to terminate grants. A copyright will be terminated precisely because it is still a productive asset, which means that any terminating author will be at risk of an unjust enrichment claim.

However, where the copyrighted work is also used as a trademark, as here, the reclaiming author will also be acquiring the goodwill in the mark, something that H/E threatened to exploit. Certainly it would be an unjust enrichment for H/E to take advantage of that value in its exploitation (assuming they can find a buyer). But we won’t get to the state law claims, since the case has settled.

The Phillies v. Harrison/Erickson, No. 19-CV-7239 (VM) (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 10, 2021)

Excellent information on termination here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.