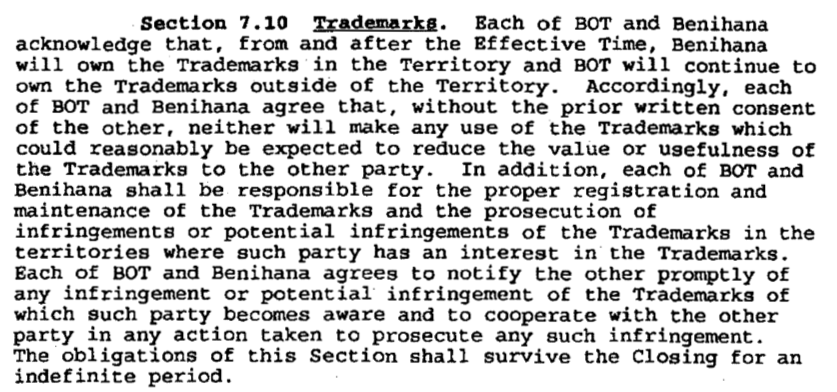

In December, 2010, plaintiff Dominion Assets assigned its patents to non-party Acacia Patent Acquisition, LLC, a subsidiary of the notorious non-practicing entity Acacia Research Corp., for Acacia to monetize. Below is the operative assignment language:

If you can’t read the image, it says:

Effective immediately upon the date of Acceptable Completion as set forth in Section 1.3 below, Assignor assigns, conveys, transfers and sells to APAC, or APAC’s designated Affiliate (as defined below) if APAC transfers or assigns its interest in this Agreement per Section 9.2 herein, the entire right, title, and interest in and to the Patents, including without limitation, all rights of Assignor to sue for past, present and future infringement of the Patents…. Assignor shall execute and deliver to APAC (or APAC’s designated Affiliate) a separate Assignment, which is attached hereto as Exhibit B, and such other documents as APAC (or APAC’s designated Affiliate) shall reasonably require in order to comply with the terms set forth in this Agreement.

The Agreement also provided in paragraph 9.7 that “Upon termination of this Agreement, the rights granted to APAC shall automatically terminate and such rights shall revert to Assignor.”

There was no dispute that Acacia provided notice of Acceptable Completion but Exhibit B, which said “For USPTO Recording” at the bottom, was never executed. For those interested in the practice of hiding the true ownership of patents acquired by patent assertion entities, the opinion noted it wasn’t executed because Acacia told Dominion “to hold off on that part as we will provide an updated copy when the time is appropriate.”

Dominion was unhappy with Acacia’s performance so about 15 months later, on March 30, 2012, it wrote to Acacia and said it was “terminating the agreement effective immediately.” In April, Acacia offered termination language, but Dominion had to accept encumbrances Acacia placed on the patents (i.e., licenses granted to Oracle, Microsoft and Samsung), and a release by Dominion of all claims against Acacia. Dominion wouldn’t sign the termination agreement with this language.

The next event in time, on May 30, 2012, was filing of the instant patent infringement lawsuit. Dominion and Acacia finally executed a Termination and Assignment Agreement effective on April 18, 2014.

So you should have noticed the argument defendant Masimo Corp. raised—who owned the patent when suit was filed on May 30, 2012? If it wasn’t Dominion, then Dominion didn’t have standing for the lawsuit.

Dominion had three arguments why it, not Acacia, owned the patent on that date. First Dominion claimed that Acacia never owned the patents in the first place because Exhibit B was never executed. That was a no-go; the operative assignment was in the main agreement and it was language of present assignment, “effective immediately upon the date of Acceptable Completion … Assignor assigns, conveys, transfers and sells to APAC … the entire right, title, and interest….” (Emphasis in original.) The fact that there was a trigger, the Acceptable Completion, did not change this into an agreement to assign in the future because the assignment was automatic upon Acceptable Completion, which had been performed. Exhibit B was not the operative assignment but rather one of “such other documents as APAC … shall reasonably require in order to comply with the terms set forth in this Agreement.” (Emphasis in original.)

Next Dominion argued that it had unilaterally rescinded the Agreement due to Acacia’s breach, but that’s an easy argument to defeat—under Texas law, one cannot unilaterally rescind a contract, it requires a court order.

Finally, Dominion argued that the parties had agreed to terminate the agreement sometime before the lawsuit was filed. This is the legal concept of mutual rescission, where, under Texas law, “parties may rescind their contract by mutual agreement and thereby discharge themselves from their respective duties.” But,

based on this evidence, the Court can at most infer that as of May 30, 2012 the parties had an agreement to negotiate a termination agreement.

The devil is in the details ….

First was the theory of verbal rescission. Under Texas law a mutual rescission doesn’t have to be in writing but there must be clear evidence of an express oral agreement or a tacit agreement inferred from the parties’ course of conduct indicating a mutual understanding that the agreement is terminated. The court acknowledged that, given that patent assignments must be in writing, there was a legal question whether a patent assignment could be rescinded verbally, but assumed without deciding that it could be.

But Dominion’s testimony wasn’t enough to establish that there had been a verbal agreement to rescind, “I don’t remember, I mean, it was just too long ago. He [an Acacia representative] just acknowledged the—the termination. And probably on more than one occasion. I don’t remember exactly what he said.” This wasn’t good enough for verbal rescission.

And the parties’ conduct belied that the contract had been rescinded before the termination agreement was finally signed:

It is evident that Acacia insisted on written termination agreement throughout the discussions regarding termination. Moreover, Acacia’s termination proposal included material terms above and beyond mere rescission of the Assignment Agreement ….

Finally a drafting tip: if you’re going to write a document confirming an event that happened in the past, don’t write it in present and prospective terms with no mention of that prior agreement or rescission. The recitals for the Termination Agreement stated that Acacia “desires to transfer and convey to Dominion all of its interests [in the covered patents],” that the “Parties desire to terminate the Patent Assignment Agreement” and that the Assignment Agreement was terminated on the “Effective Date” of the Termination Agreement, in 2014. That’s pretty much the nail in the coffin of your claim that there was an earlier effective termination.

There’s no hint in the case, but you can sort of see the back story here. Dominion was aware of defendant Masimo’s infringement and unhappy that Acacia wasn’t pursuing it, so wanted to pursue the case itself. That was the urgency in filing suit before the ownership situation was more cleanly managed. But it didn’t pay off.

Dominion Assets LLC v. Masimo Corp., No. 112-cv-02773-BLF (N.D. Calif. June 27, 2014)

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.