When I started writing this post I was going to write about a case that had sussed out that there are different legal thresholds for determining ownership for purposes of prosecuting a patent versus what may be challenged by the PTO in an appeal of a rejection. But it turns out the conclusion was constructed entirely of strung-together quotes from unrelated cases having nothing to do with the legal situation being evaluated, so the decision is completely unreliable. Oh well. Now that it’s written I’m not going to delete it, and leave it as a caution that opinions are only as good as their reasoning.

There were six named inventors on a patent application, Application No. 07/773,161, that was abandoned in 1993. In 2007 two of them, Bono and Martillo, filed a petition to revive the application, explaining that Bono and Martillo were the only owners of the patent application. The PTO issued two orders to show cause challenging their claim of ownership; meanwhile Bono and Martillo assigned their ownership interest to plaintiff Realvirt, LLC. The PTO ultimately issued a decision stating that Bono and Martillo had sufficiently demonstrated ownership. Realvirt could therefore proceed with the prosecution of the application.

The application was ultimately finally rejected, a decision that was affirmed by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board and a rehearing was denied. Realvirt appealed the rejection to the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia under 35 U.S.C. § 145.

In the Patent and Trademark Office Answer, it pled affirmative defenses that “[u]pon information and belief, plaintiff does not own all right, title, and interest in the ‘161 Application, and therefore lacks standing to sue based on the ‘161 Application,” and (ii) “[a]lternatively, other owner(s) in the ‘161 Application are indispensable parties to this action, mandating dismissal if they cannot be joined in this litigation.” Realvirt moved for summary judgment that the PTO was barred from raising ownership of the patent application as a defense.

Realvirt’s theory was collateral estoppel, “once an issue is actually and necessarily determined by a court of competent jurisdiction, then determination is conclusive in subsequent suits based on a different cause of action involving a party to the prior litigation.” The court acknowledged that in some circumstances the factual findings of an administrative body can preclude later litigation of the same situation, but concluded they categorically did not here:

These principles, applied here, compel the conclusion that the collateral estoppel doctrine does not apply to bar the PTO’s standing argument. To begin with, “there is a general consensus among courts that … [a] patent prosecution is not an adversarial, litigation-type proceeding, but a wholly ex parte proceeding before the PTO” because “‘although the process involves preparation and defense of legal claims in a quasi-adjudicatory forum, the give-and-take of an adversary proceeding is by and large absent.’” In re Method of Processing Ethanol Byproducts & Related Subsystems (‘858) Patent Litig., No. 1:10-ML-02181-LJM, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 88512, 2014 WL 2938183, at *7-8 (S.D. Ind. June 30, 2014) (quoting Hercules, Inc. v. Exxon Corp., 434 F. Supp. 136, 152 (D. Del. 1977)). Indeed, PTO proceedings lack the opportunity for cross-examination, discovery, and other tools available to adversarial litigants, and in fact, “because of the ever increasing number of applicants before it,” the PTO “must rely,” as occurred here, “on applicants for many of the facts upon which its decisions are based.” Norton v. Curtiss, 433 F.2d 779, 793, 57 C.C.P.A. 1384 (C.C.P.A. 1970). Thus, where, as here, the underlying administrative proceedings were non-adversarial and wholly ex parte it is clear that the doctrine of collateral estoppel does not apply. Elliott, 478 U.S. at 797-98; see also Regions, 522 U.S. at 463-64 (holding that “[a]bsent actual and adversarial litigation … principles of [collateral estoppel] do not hold fast”).

This conclusion strikes me as odd. First, it never cited the 2015 B&B Hardware, Inc. v. Hargis Indus., Inc. decision, a Supreme Court case involving whether an inter partes Trademark Trial and Appeal Board decision can have preclusive effect. That seems like a pretty relevant precedent to me. Instead, the cases cited here involve whether patent prosecution materials are attorney work-product, prepared “in anticipation of litigation,” a very different question than whether an administrative appeal should have preclusive effect.

B&B Hardware rejected categorical exclusion of collateral estoppel:

Both this Court’s cases and the Restatement make clear that issue preclusion is not limited to those situations in which the same issue is before two courts. Rather, where a single issue is before a court and an administrative agency, preclusion also often applies. Indeed, this Court has explained that because the principle of issue preclusion was so “well established” at common law, in those situations in which Congress has authorized agencies to resolve disputes, “courts may take it as given that Congress has legislated with the expectation that the principle of issue preclusion will apply except when a statutory purpose to the contrary is evident.” This reflects the Court’s longstanding view that when an administrative agency is acting in a judicial capacity and resolves disputed issues of fact properly before it which the parties have had an adequate opportunity to litigate, the courts have not hesitated to apply res judicata to enforce repose.

(Quotation marks, brackets and citations omitted.) Indeed there may be procedural differences between an ex parte appeal and an inter partes challenge that may militate a different outcome, but it would have been nice to have that analyzed.

We move on. The Realvirt court concluded that even if collateral estoppel applied the elements weren’t met:

[T]his preliminary determination for purposes of proceeding with the prosecution of the ‘161 Application was in no way a “final” decision as to ownership, but was instead a threshold finding that the PTO could proceed with the prosecution of the ‘161 Application. Indeed, the PTO cannot—and does not—determine ownership of patent applications because questions of title are grounded in state law. Akazawa v. Link New Tech. Int’l, Inc., 520 F.3d 1354, 1357 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (“Our case law is clear that state law, not federal law, typically governs patent ownership”). When the ownership of a patent application is unclear, the PTO will, as necessary to advance prosecution, “determine what effect a document has, including whether a party has the authority to take an action in a matter pending before the [PTO].” Id.

We’ll pause here. Akazawa doesn’t say that. Instead, the last quote appears to be from 37 CFR 3.54, the rule on recording documents. The rule makes the unremarkable statement that the act of recording of a document is not a determination by the PTO that the document is valid or what effect it has on title. But the rule goes on further to say “When necessary, the Office will determine what effect a document has, including whether a party has the authority to take an action in a matter pending before the Office.” There is no limitation that it will only “do so as necessary to advance prosecution” and there is no suggestion in the rule that the PTO isn’t competent to make a determination, even one under state law,* who the owner of a patent application is.

We continue:

Yet, contrary to plaintiff’s contention, any such finding by the PTO, through the OPLA, is a preliminary finding to determine whether a prosecution may proceed. As such, the preliminary finding is not a final adjudication as to the ownership of the patent application; rather, ownership of the patent application is a matter of state law that must be determined by a court.

So without any citation, the court concluded that the ownership determination could only be a “preliminary finding” by the PTO and that the PTO may not reach legal conclusions about patent ownership because only a court may do so. Which may or may not be true, but we surely don’t know from this opinion.

Here it is, for what it’s worth. Realvirt, LLC v. Lee, No. 1:15-cv-963 (E.D. Va. April 14, 2016).

*Ownership originally vests in the inventor and a question of inventorship is a federal one. So not even all questions of ownership are under state law.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

When: Monday, May 23, 2016, from 8PM to 11PM

When: Monday, May 23, 2016, from 8PM to 11PM

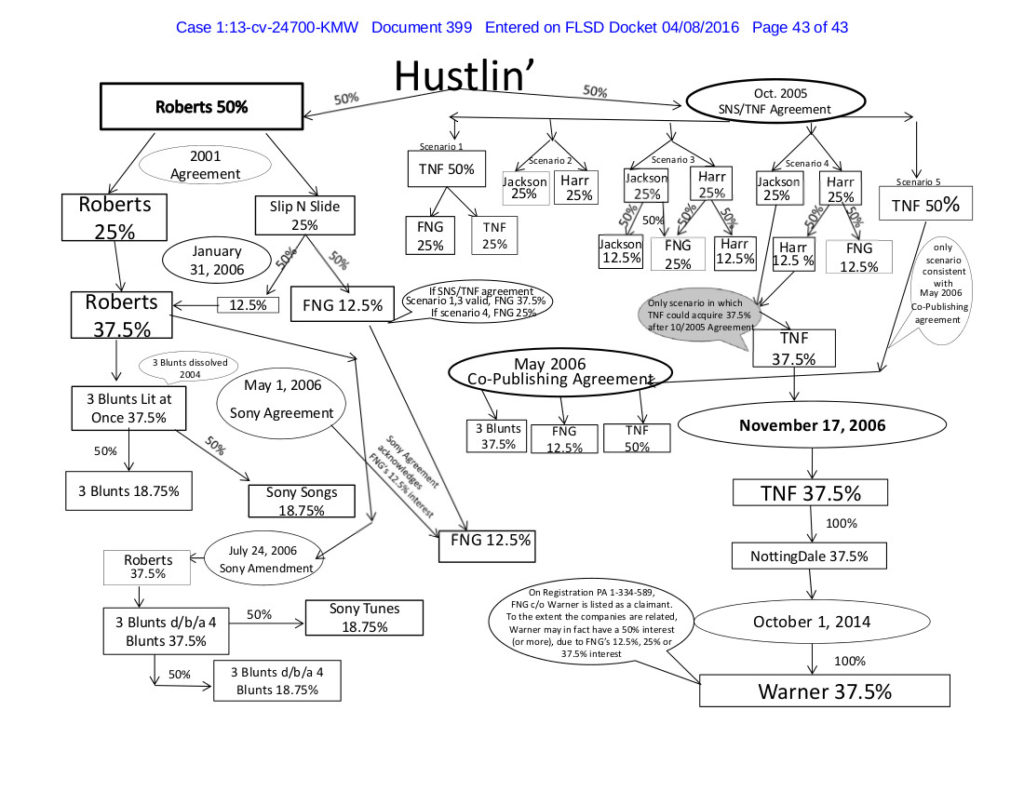

I previously posted about a copyright infringement suit with three registrations for the same work, brought by William L. Roberts aka Rick Ross, and Andrew Harr and Jermaine Jackson aka The Runners, alleging infringement of a musical work titled “Hustlin’.” I asked what happens on a motion for summary judgment on the questions “was the musical composition Hustlin’ validly registered by the Copyright Office, and, if so, do Plaintiffs have an ownership interest in the exclusive right to prepare derivative works for the musical composition Hustlin’?”

I previously posted about a copyright infringement suit with three registrations for the same work, brought by William L. Roberts aka Rick Ross, and Andrew Harr and Jermaine Jackson aka The Runners, alleging infringement of a musical work titled “Hustlin’.” I asked what happens on a motion for summary judgment on the questions “was the musical composition Hustlin’ validly registered by the Copyright Office, and, if so, do Plaintiffs have an ownership interest in the exclusive right to prepare derivative works for the musical composition Hustlin’?”