I’ve read a lot of cases with convoluted fact patterns, which I guess is how they end up in litigation. But C.F.M. Dist. Co. v. Costantine, an opposition before the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board, is in the stratosphere of convoluted. Not surprisingly, it’s about a family business.

In a 44-page decision, 4 pages are introductory, 6 relate to procedural matters, and a full 20 pages are dedicated to a recitation of the facts, including a family tree, a family photo of some of the parties, and 5 pages devoted solely to a 50-year timeline (pp. 25-30 if you’re really interested).

The case is so complicated I’ll describe it only in the most general terms, although that will suffice for the purposes of this post. These are the marks in dispute:

The marks (applications here and here) are used for restaurant services, although we’ll get into more details about the kind of restaurant services in a minute.

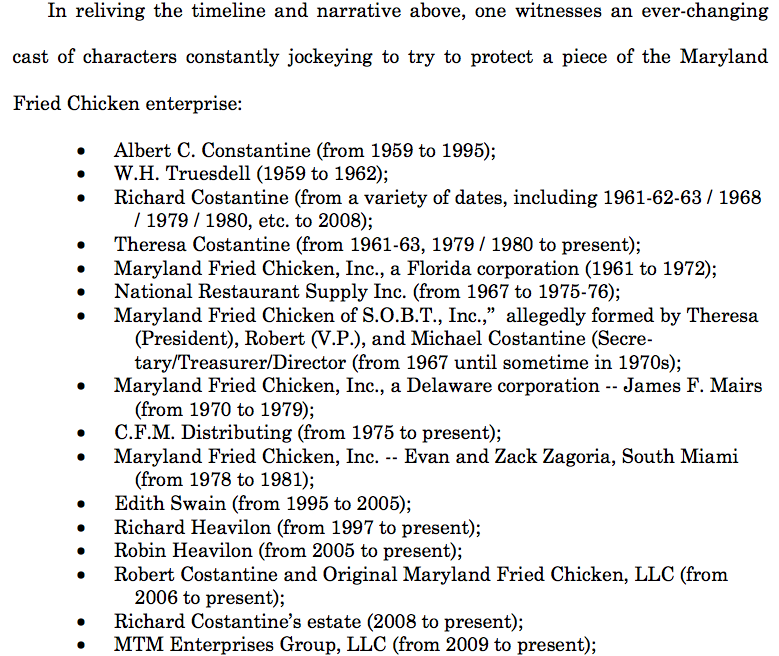

One of three brothers in the Constantine/Costantine family (apparently there isn’t even agreement on how to spell the name) was the first to use “Maryland Fried Chicken.” Everything after that is a morass of uses by various family members (wives, brothers and sons), assignments, including one nunc pro tunc to a date fourteen years earlier and one done, allegedly, while the assignor was incompetent, corporate mergers, corporations formed by unknown third parties, and informal licenses to somewhere around 30 restaurants. After the recitation of facts, the Board helpfully summarized all the players (you don’t have to pay attention to the names, it’s for illustration):

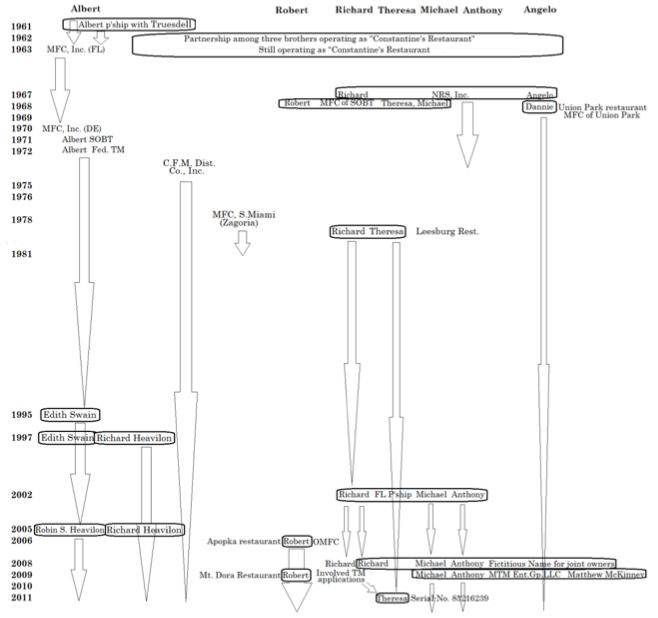

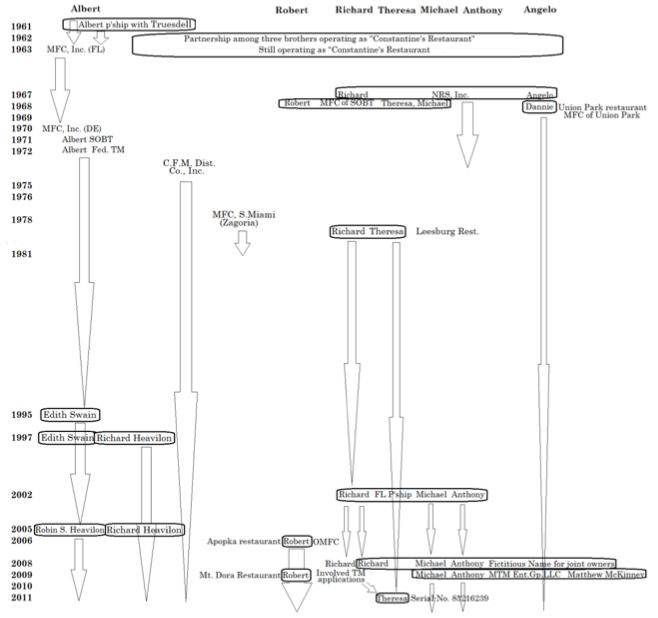

And let’s not miss this graphic representation, offered by the Board to try to clarify who owned what and when:

I confess excitement about this decision because the Board based its analysis on an approach I suggested in a Trademark Reporter article, Who Owns the Mark? A Single Framework for Resolving Trademark Ownership Disputes, 96 Trademark Rep. 681 (2006). That is, the Board said:

[i]n deciding which party, if any, owns these various composite marks, we look to three separate interests, namely contractual expectation, responsibility for the quality of the goods and/or services, and consumer perception.

Regarding contractual expectation, no one had a claim to an unbroken chain of title for the marks. Further, despite the number of restaurants using the mark, there was no unified franchising scheme; at most there was an informal effort to ensure that no two stores were located too close together. Opposer C.F.M., who distributed the supplies the restaurants bought, didn’t even claim that it was a franchisor; it’s only business interest was supplying the various stores with their product.

It gets even more interesting when the Board looks at the quality of the goods and services. I apologize for the lengthy excerpts below, but the you only get the full color in the details:

[W]e find that since the mid- to late-70s, as the Constantine/ Costantine family was engaged in a frenetic game of corporate/ partnership/proprietorship/joint-grouping musical chairs, no one has really maintained any responsibility for the quality of the food products or services offered at retail under these marks….

Other than the actual food itself (e.g., chicken, potatoes, cabbage, etc.), C.F.M. provides most everything else that most Maryland Fried Chicken restaurants use day-in and day-out. This includes breading mixes, its proprietary coleslaw dressing, five different sizes of carry-out food containers, pre-packaged meal kits (e.g., napkins, spork/fork, wet towelette, salt packets, etc.), all imprinted with the Maryland Fried Chicken logo, as well as paper towels, toilet paper, chemical cleaners, etc.

Otherwise, all the Maryland Fried Chicken restaurants are quite different. James Gourley and Paul Dion testified that each one of the thirty Maryland Fried Chicken restaurants can serve whatever its owner desires. There is no requirement that a Maryland Fried Chicken restaurant serve the same fried chicken products. In fact, the taste of the fried chicken products at retail can vary widely. Some restaurants are offering chicken that is crunchier than that of other Maryland Fried Chicken outlets. A customer will notice the chicken as served at various outlets has more or less salt, more or fewer spices, different cooking oils and different styles of marination. Although C.F.M. provides a consistent breading mix product, individual restaurant owners use it quite differently in deriving the house recipe – some using the C.F.M./MFC branded breading mix alone, other using it with its own unique ingredients, while yet others choose not to use a C.F.M. breading mix at all. For example, the owner of the Winter Garden restaurant uses the C.F.M. house brand of breading mix (not that traded by C.F.M. under the Maryland Fried Chicken label) and then adds another completely different mix of his own choosing.

While most Maryland Fried Chicken restaurants do sell fried chicken, even that is not strictly a requirement. Some sell barbeque chicken, while others specialize in steak, pork, Brunswick stew, pizza or seafood. In fact, a number of Maryland Fried Chicken outlets are known more prominently as “Shrimper Seafood” outlets because an entire chain of seafood restaurant owners decided this was a convenient way to offer chicken in addition to shrimp. The record also shows that some Maryland Fried Chicken restaurants specialize in Greek, Mexican, Chinese or other Asian cuisine. Therefore, consumers can get one product and product selection from one Maryland Fried Chicken restaurant and something entirely different at another Maryland Fried Chicken location.

As to the external appearance of Maryland Fried Chicken buildings, outdoor painting schemes are quite different, as is the signage. The Albany store has a rooster mural, some chicken logos have the hen with two little chicks, another prominently displays the image of a chef with a hat, while yet another features a large mural of Bob Marley on the outside wall of the restaurant. The internal décor is also quite different among the stores, including some featuring Asian décor. The outlets each display significantly different type of menus, menu boards and internal signage. Some smaller locations have minimal seating, while others are fairly large sit-down restaurants.

As one travels from restaurant to restaurant, one will notice that there are not similar uniforms provided for staff members. Some owners provide employees with T-shirts from C.F.M., while others create their own artwork and hire a silk-screen artist or local T-shirt company to make whatever designs they want. In some restaurants, employees simply wear regular street clothes, while in yet others they might don aprons. No one provides standardized training for employees from restaurant to restaurant, and the retail prices vary widely from outlet to outlet.

The third prong, consumer perception, fared no better:

The members of the public in the southeastern portion of the United States, and especially in Central Florida, have been faced for decades with products and services bearing visually similar Maryland Fried Chicken trademarks and service marks. However, with each outlet having such diverse qualities, we find that these logos have totally lost any of their earlier abilities to identify a sole source. It would seem at this late date that very few members of the consuming public in Central Florida (or elsewhere) still contemplate a single enterprise as standing behind the Maryland Fried Chicken products or services. Those few who do anticipate the consistent quality of the prototypical franchise operation will likely find themselves disappointed as they take their business from one Maryland Fried Chicken outlet to another. Certainly, if one has an unpleasant experience at a particular Maryland Fried Chicken restaurant, there is not one single entity to whom that aggrieved customer could turn with a complaint.

Concluding:

Whether or not one relies upon language of abandonment or naked licensing, the uncontrolled use of an alleged mark by many different parties is anathema to the role and function of a source indicator. Through conscious acts of commission taken by various family members, any property rights that existed in the 1960s appear to have been totally splintered. Repeated and inconsistent transfers of alleged bundles of sticks by constantly realigned individuals and groups of persons has created total confusion about who, if anyone, was in charge of this one-time family enterprise. Continuing acts of omission over recent decades on the part of applicant have further caused these alleged marks to lose any remaining significance as indicators of source….

[W]hatever the designs of Albert Constantine in the early 1960s, the current confusing state of affairs seems to have been accepted by most of the actors, and no one rocks the boat until such point as one party makes a play for exclusivity that threatens the other players. The litigation surrounding these applications seems to have been such an event. Unfortunately, we see no reason to think the pieces of this would-be franchise can ever be put back together. These parties have lost their trademark rights against the world, and thus against each other. Accordingly, despite, for example, C.F.M.’s claims of its priority over that of applicant, we view the several opposers’ actions herein to be less an attempt to claim rights in these marks for themselves, but instead merely wanting to maintain the status quo by keeping applicant from being able in the future to assert a right to which it is not entitled, under the facts of the case.

The current hodge-podge arrangement that is Maryland Fried Chicken is clearly not optimal. On the other hand, given the state of play, the status quo is preferable to the scenario where a single player, like applicant, is given the imprimatur of a federal registration and the appearance of exclusivity, when in reality – to quote Gertrude Stein’s famous observations about Oakland – “There is no there there.”

In conclusion, we find that applicant was not the owner of these marks at the time the applications were filed, and consequently, both of these involved applications are deemed to be void ab initio. As discussed throughout this opinion, we find that the traditional concepts of priority and likelihood of confusion are of little help in resolving these disputes, and we do not reach the questions of whether applicant has committed fraud on the United States Patent and Trademark Office by filing these applications.

What I like most about this decision is that it take the broad view. A mechanical slog through one legal doctrine or another might have allowed the applicant to fall through a crack and get the registration. Instead, we reach a result that comports with reality, which is that there is no sole owner of all these different uses of the mark, but, at most, a number of concurrent owners. I also appreciate the Board’s recognition of the power of a federal registration and its effort to avoid awarding it wrongly.

Too bad it’s not precedential.

And a HT to John Welch, who not only sent me the opinion, but is also the person who many years ago critiqued the article I was writing and suggested submitting it to the Trademark Reporter.

C.F.M. Dist. Co. v. Costantine, Opp. No. 91185766 (TTAB March 20, 2013).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.