The legal significance of a “license” to the BUTTERNUT trademark has been in dispute for ten years now. I put “license” in quotes because while the document in question is called a license, it’s not your typical trademark license.

The legal significance of a “license” to the BUTTERNUT trademark has been in dispute for ten years now. I put “license” in quotes because while the document in question is called a license, it’s not your typical trademark license.

In 1996, in settlement of an antitrust suit brought by the Justice Department, defendant Interstate Bakeries Corporation (IBC) had to divest itself of some Bread Assets (land, buildings, fixtures, equipment, vehicles, customer lists, etc.) and Labels, which included “all legal rights associated with a brand’s trademarks, trade names, copyrights, designs and trade dress.”

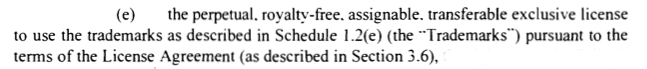

Plaintiff Lewis Brothers Bakeries (LBB) was the company that acquired the rights Interstate Brands had to sell. The judgment was reduced a transaction that had both an Asset Purchase Agreement and a License Agreement. One of the assets being transferred in the APA was:

If you can’t see the image, it says “the perpetual, royalty-free, assignable, transferable exclusive license to use the trademarks as described in Schedule 1.2(e)(the “Trademarks”) pursuant to the terms of the License Agreement (as described in Section 3.6) …” Section 3.6 described a “trademark license agreement substantially in the form of Exhibit G hereto ….”

If you can’t see the image, it says “the perpetual, royalty-free, assignable, transferable exclusive license to use the trademarks as described in Schedule 1.2(e)(the “Trademarks”) pursuant to the terms of the License Agreement (as described in Section 3.6) …” Section 3.6 described a “trademark license agreement substantially in the form of Exhibit G hereto ….”

So we have what is a very unusual trademark license agreement. Most trademark license agreements aren’t assignable, transferable or perpetual, and when you add in “exclusive” you get an agreement that looks much more like a transfer of all rights rather than a license.

In 2004 defendant Interstate Bakeries filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. As part of its reorganization plan, it identified the license agreement as an executory contract that it was going to assume.

The bankruptcy court, the district court, a panel of the Eighth Circuit and the Eighth Circuit sitting en banc have all now opined. The fundamental question is whether this license agreement is an executory contract. If it is, Interstate Bakeries can assume the agreement, perhaps assigning it to someone else—which it did, assigning it to Flowers Foods during the pendency of the case. A decision that the agreement is not executory, as explained by the court, “would affect the value of LBB’s exclusive, perpetual, royalty-free license by removing uncertainty about the status of the License Agreement. A judgment in favor of LBB also would allow the company to plan its ongoing business without the potential that Flowers Foods or any other successor or assign of IBC could reject the License Agreement in a later bankruptcy proceeding.”

The bankruptcy court held that the license was executory because both parties had material, outstanding obligations. LBB’s obligation included the duty to maintain the character and quality of the goods sold under the trademark, what all trademark lawyers recognize as a fundamental duty of a trademark licensee. Interstate Bakeries’ obligations included the typical duties of a trademark owner, like maintaining and defending the trademarks and refraining from using the marks itself in the territory.

The district court and the 8th Circuit panel both agreed that the license agreement was executory, with a dissenting judge on the panel. The court of appeals decided to hear the case en banc.

And LBB finally has its relief. Rather than looking at the license agreement alone, as all three previous opinions had done, the full court considered the the transaction in its entirety, as an asset purchase:

Applying these principles, the Asset Purchase Agreement and the License Agreement should be considered together as one contract. IBC and LBB entered into the Asset Purchase Agreement and the License Agreement contemporaneously on December 28, 1996. The Asset Purchase Agreement lists the license as an asset sold to LBB pursuant to the sale. It directs the parties to enter into the License Agreement “[u]pon the terms and subject to the conditions contained in [the Asset Purchase Agreement].” Both documents memorializing the agreements define the “Entire Agreement” as including both agreements. The Asset Purchase Agreement’s definition includes “the exhibits and schedules hereto,” and a model for the License Agreement is included as an exhibit to the Asset Purchase Agreement…. To treat the License Agreement as a separate agreement would run counter to the plain language of both the Asset Purchase Agreement and the License Agreement, which describe the two as one piece, and would ignore the valuable consideration paid for the license.

And, looking at the two agreements as the whole instead of the license agreement alone, the court found that the license agreement was not executory because the transaction, the asset purchase, was substantially performed:

The essence of the agreement here was the sale of IBC’s Butternut bread and Sunbeam bread business operations in specific territories, not merely the licensing of IBC’s trademark. The agreement called for LBB to pay $20 million for IBC’s assets. The parties allocated $11.88 million for tangible assets, such as real property, machinery and equipment, computers and licensed computer software, vehicles, office equipment, and inventory. They allocated another $8.12 million toward intangible assets, including the license. IBC has transferred all of the tangible assets and inventory to LBB, executed the License Agreement, and received the full $20 million purchase price from LBB.

IBC’s remaining obligations concern only one of the assets included in the sale—the license. They involve such matters as obligations of notice and forbearance with regard to the trademarks, obligations relating to maintenance and defense of the marks, and other infringement-related obligations. When considered in the context of the entire agreement, these remaining obligations are relatively minor and do not relate to the central purpose of the agreement to sell the Butternut and Sunbeam bread operations and assets to LBB in certain territories.

Despite my discomfort with the concept that a trademark license is not categorically executory, I agree with this outcome. In the bankruptcy court there was testimony from the former GC of Interstate that Interstate’s intent was to sell the BUTTERNUT trademark to LBB within LBB’s territory. The vehicle of a trademark license was used because Interstate continued to own the trademark in other territories. So fundamentally, there shouldn’t have been a license at all, but instead a territorial division of ownership. Which is what the Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit has effectively now accomplished.

Lewis Bros. Bakeries Inc. v. Interstate Brands Corp., No. 11-1850 (8th Cir. June 6, 2014).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.