In a contest that requires a creative contribution, the contest sponsor will generally require that the participant assign the copyright in the contributed work. LittleMismatched did no differently, but it ran into some trouble because its target demographic is young girls. Mix children and contract and it gets a little trickier.

The plaintiff, I.C., was a second grade student. Defendant LittleMisMatched is a girls’ clothing brand that features mismatched but coordinated designs. LittleMisMatched ran a T-shirt design contest through I.C.’s school. The contest entry included a copyright assignment:

By entering, you agree that your entry shall be a “work made for hire” with all rights therein, including, without limitation, the exclusive copyright, being the property of Sponsor. In the event the entry is considered not to be a “work made for hire,” by entering, you irrevocably assign to Sponsor all right, title, and interest in your Content, design and entry (including, without limitation, the copyright) to Sponsor, including in any and all media whether now known or hereafter devised, in perpetuity, anywhere in the world, with the right to make any and all uses thereof, including, without limitation, for purposes of advertising or trade. You agree Sponsor may use any non-winning entered design in its products, without compensation of any kind to you, the entrant.

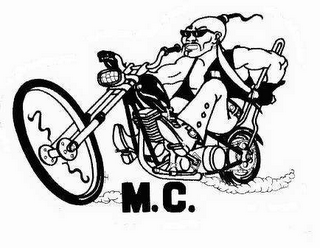

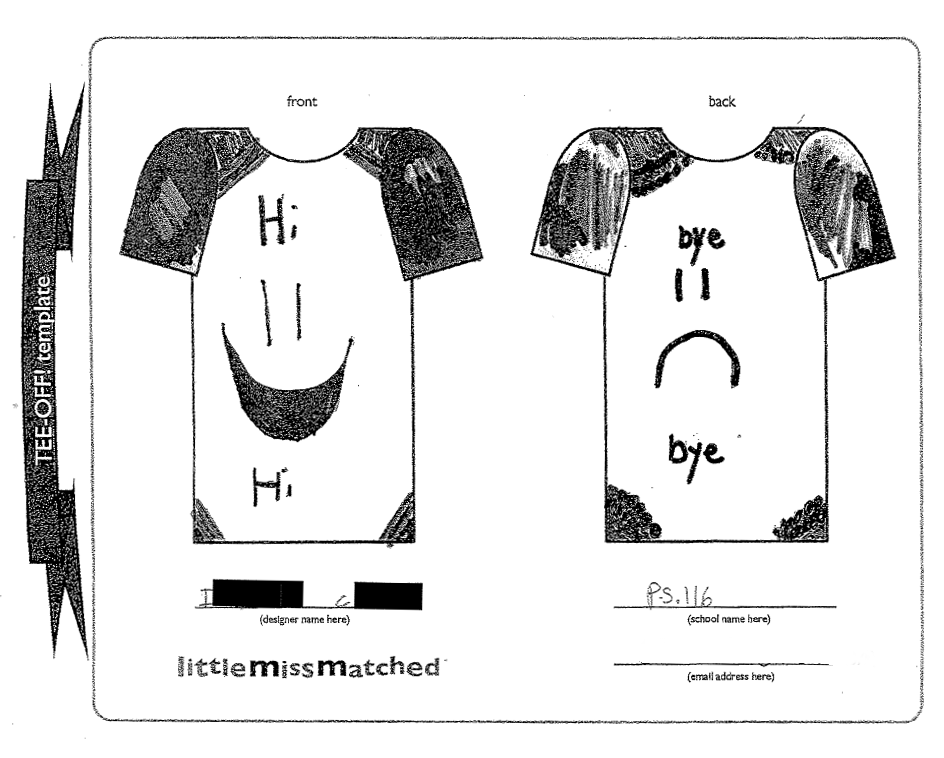

I.C. submitted this design:

I.C. and her mother both signed the entry. I.C. was one of two winners in her school and was awarded a $100 gift card and five t-shirts with her design. LittleMisMatched then turned the design into an entire line of “Hi-Bye” goods, including socks, purses, tights, pants and earmuffs.

I.C. and her mother both signed the entry. I.C. was one of two winners in her school and was awarded a $100 gift card and five t-shirts with her design. LittleMisMatched then turned the design into an entire line of “Hi-Bye” goods, including socks, purses, tights, pants and earmuffs.

I.C. filed an application to register the copyright in her design, which was refused registration, and wrote to LittleMisMatched to disaffirm the contract. I.C. then sued.

I.C. first alleged that there wasn’t mutual assent because of her youth. But

I.C. (and her mother) signed a written agreement. Although she is a minor, “[she] who signs or accepts a written contract, in the absence of fraud or other wrongful act on the part of another contracting party, is conclusively presumed to know its contents and to assent to them, and there can be no evidence for the jury as to [her] understanding of its terms.” … If minors could simply claim that they never assented to the terms of written agreements due to their age, then the contracts of minors would generally be void. But the protection New York law provides to minors is to allow them the right to disaffirm a contract, as discussed below, not to find that no enforceable contract exists. “Infancy does not disable one from entering into contracts, and . . . [her] position and [her] acts are those of any responsible person.” Plaintiff cannot claim lack of mutual assent on the basis of her age alone.

I.C. next claimed that the contract was voidable because of her infancy, but

defendants correctly note that a minor cannot disaffirm a contract where doing so would put her in a better position than she otherwise would have been absent the contract. It has long been established under New York law that “[t]he privilege of infancy is to be used as a shield, and not as a sword.” …

The Court finds that plaintiff is precluded from disaffirming the contract. Although the complaint alleges that plaintiff tendered the $100 gift card and t-shirts she received for winning the contest, repudiating the contract would nevertheless put her in a superior position than she would have occupied had she never entered the contest. Prior to submitting her contest entry, plaintiff owned a simple hand-drawn design on a template provided by Miss Matched. But by repudiating the contract after Miss Matched has created an entire catalogue of clothing and accessory lines using the design, plaintiff would regain ownership of the design at a significant advantage—after Miss Matched has spent resources developing and marketing that catalogue. Plaintiff may not retain this “fruit of the contract” under New York law.

But the court entertained one theory—unconscionability. The party alleging the defect must show that the contract was both procedurally and substantively unconscionable, and I.C. was able to barely squeak in with the theory:

Plaintiff offers several reasons as to why the contest rules are procedurally unconscionable, relying heavily on the purported disparity in bargaining power between I.C., a second grader, and Miss Matched, a sophisticated business, when she agreed to the terms of the contest rules. Plaintiff also argues that by conducting the contest through the auspices of the school, Miss Matched used the school’s position of authority to induce I.C.’s participation in the contest. Without the benefit of an evidentiary hearing, the Court agrees that the complaint contains sufficient factual allegations to plausibly claim procedural unconscionability…. Notwithstanding, the Court notes that I.C.’s mother also signed the submission form. I.C.’s mother is assumed to have read the terms of the contest before she signed the submission form. At the evidentiary hearing, the Court will evaluate all of the relevant facts related to the contract’s formation, not only whether the contract formation process between Miss Matched and I.C. was procedurally unconscionable—as alleged in the complaint and therefore accepted as true for purposes of this motion—but also whether the process was procedurally unconscionable between Miss Matched and I.C., as advised and supervised by her mother.

Plaintiff also argues that the terms of the contest were substantively unconscionable because she was not provided compensation for sales of merchandise featuring the Hi/Bye design. The Court has doubts as to whether plaintiff can demonstrate substantive unconscionability. At the time Miss Matched created the contest, it expected to receive simple hand-drawn designs by elementary school children on a basic template it provided. Although the prizes awarded were relatively modest, I.C. only owned a simple drawing at the time she submitted her contest entry—one whose creation was prompted by the contest itself—rather than a design supporting an entire catalogue of merchandise. Nevertheless, because procedural and substantive unconscionability operate on a “sliding scale,” the prudent course is for the Court to defer judgment on substantive unconscionability, pending an evidentiary hearing, so that both procedural and substantive unconscionability can be evaluated together.

Plaintiff’s complaint alleges facts sufficient to warrant an evidentiary hearing regarding the unconscionability of the contest rules.

The goal of the contest was to get designs and LittleMissMatched succeeded remarkably well, albeit ending up defending a lawsuit. But its intentions couldn’t have been clearer.

The opinion also reminds us of the notice requirement advising the Copyright Office of an infringement claim asserting a infringement of a work for which registration was refused.

I.C. ex rel. Solovsky v. Delta Galil USA, No. 1:14-cv-7289-GHW (Sept. 26, 2015).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.