Does an exclusive agent for a photographer have standing to bring a copyright infringement suit on behalf of that photographer? The Ninth Circuit has said yes; the Northern District of Georgia says no.

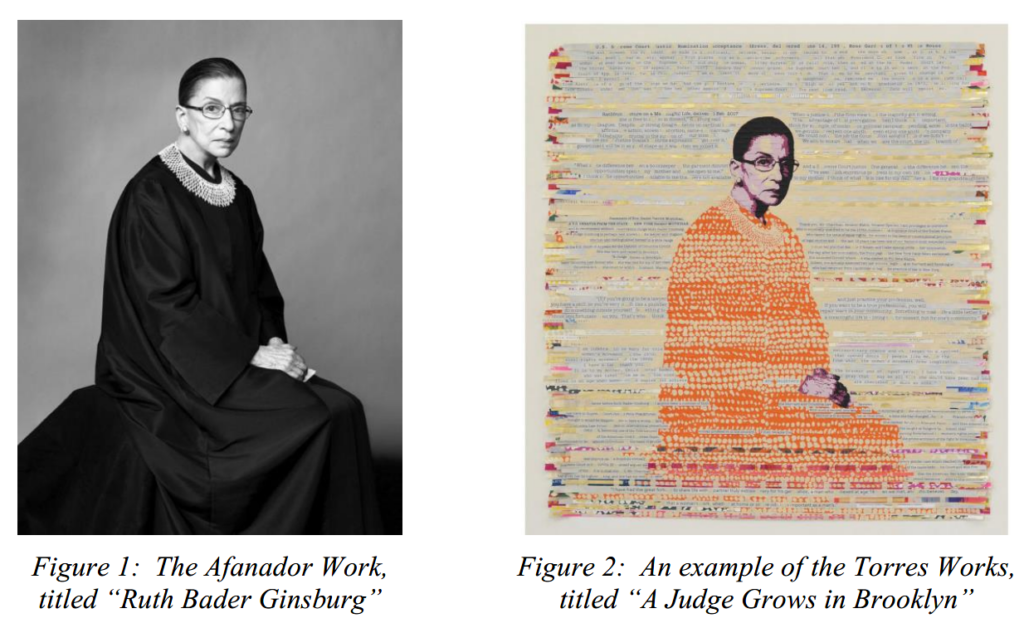

Plaintiff Creative Photographers, Inc. (“CPi”) represented non-party photographer Ruvén Afanador. The defendants are accused of infringing the copyright in one of his works:

In the agreement between CPi and Afanador the relevant language was this:

You retain [Plaintiff] as your exclusive agent to sell, syndicate, license, market or otherwise distribute any and all celebrity/portrait photographs and related video portraits, submitted to us by you and accepted by us for exploitation for sale or syndication during the term of this Agreement (the “Accepted Images”). You must be the sole owner of the copyright for all such photographs and may not offer any celebrity/portrait photographs for sale or syndication to or through any other agent, representative, agency, person or entity during the Term of this Agreement.

Based on this language, CPi brought suit in its own name against the defendants. Is this language that transfers to CPi one of the exclusive rights of copyright that would give it statutory standing to file a copyright infringement lawsuit?

The court relied on an earlier district court opinion in the same circuit, Original Appalachian Artworks, Inc. v. Schlaifer Nance & Co., 679 F. Supp. 1564 (N.D. Ga. 1987), for the proposition that “a grant of the right to act as an ‘exclusive agent’ for a copyright owner in authorizing others to use a copyrighted work is a mere contractual right, not a copyright enforceable under the Copyright Act.” (emphasis in original).

The CPi agreement granted it the right “to sell, syndicate, license, market or otherwise distribute” the Afanador work. CPi claimed this language was “a clear, explicit and exclusive grant of [§] 106 rights” in the Afanador work.

The court disagreed:

It is true that in Original Appalachian, SN & C did not tie their standing argument to a specific § 106 right; instead, SN & C contended that “the expansive language describing the [§] 106 rights was broad enough to encompass SN & C’s exclusive right to authorize other to us the OAA’s copyright. … However, … [t]he [CPi] Agreement “explicitly and conclusively” makes Plaintiff Afanador’s agent but its terms do not otherwise expressly convey to Plaintiff an exclusive license to any of the § 106 rights. Other than reciting the text of the Agreement and asserting that the language confers § 106 rights, Plaintiff simply has not provided this Court with legal authority or other argument to interpret this language in any other manner.

The district court found support in several cases out of Colorado (one blogged here) brought by stock photo agency Viesti, which reached the same conclusion that the agency agreement did not give the agent standing for an infringement suit.

The Ninth Circuit has, though, in Minden Pictures, Inc. v. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. held that a photographers’ agent had standing for a copyright infringement suit. I’ve always struggled with this decision and the Georgia court here distinguished it based on the different wording of the agreements at issue in the two cases:

However, Minden is distinguishable. The agency agreements in that case contained clear language indicating that they transferred to Minden an exclusive right (rather than merely appointed Minden as an exclusive agent): “The [a]greements also confer upon Minden ‘the unrestricted, exclusive right to distribute, License, and / or exploit the Images … without seeking special permission to do so.’ ” The Agreement in this case lacks any such language. In Minden, too, it seemed fairly clear that the agency agreements constituted some kind of license; the analysis hinged on whether that license was exclusive or nonexclusive. Here, though, while the Agreement certainly makes Plaintiff an exclusive agent to perform for Afanador certain functions, the Court does not agree with Plaintiff that the Agreement, on its face, constitutes an exclusive license. Finally, the Court is also more inclined to find authority from this circuit, like Original Appalachian, persuasive than a case from another circuit altogether.

CPi had a second standing problem. CPi characterized the defendants’ works as “derivative works” in the complaint, but the agency agreement didn’t grant any license to CPi for derivative works:

Although Plaintiff asserts in the First Amended Complaint that it holds an exclusive right to prepare derivative works, this is a legal conclusion that the Court need not accept as true. In any case, the Agreement clearly shows to the contrary. Thus, even if Plaintiff held an exclusive license under the Agreement, it does not appear that Plaintiff holds an exclusive license to the right—the preparation of derivative works—that it alleges Defendants infringed.

Case dismissed with leave to amend. I don’t know if we’re headed to a circuit split; I think it depends on whether the 9th Circuit doubles-down on its holding or finds a way to walk it back. But its reasoning doesn’t seem to be getting traction with any other courts.

Creative Photographers, Inc. v. Julie Art, LLC, No. 1:22-CV-00655-JPB (N.D. Ga. Mar. 13, 2023)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Leave a Reply