The Camellia Grill was a New Orleans restaurant that closed in 2005 after Hurricane Katrina. Various aspects of the business were owned by various entities owned by Michael Shwartz; for our purposes we’ll just refer to them all as “Shwartz.”

In August, 2007, Shwartz entered into several agreements with Hicham Khodr and various companies he wholly owned to sell the business. Two entities are relevant, Uptown Grill, LLC and Grill Holdings, LLC.

On August 11, 2007 Shwartz sold the immovable property at the restaurant’s location, 626 Carrollton Avenue, to a Khodr entity. No aspect of this sale is disputed.

On the same day, Shwartz executed a Bill of Sale to Khodr entity Uptown Grill. Exactly what was transferred is the subject of this lawsuit.

Sixteen days later, on August 27, 2006, the parties entered into a license agreement, with Shwartz exclusively licensing the registered Camellia Grill trademarks to Khodr entity Grill Holdings nationwide for $1,000,000.

The dates aren’t clear, but by 2011 Shwartz had alleged breach of the license agreement and gave Grill Holdings notice that the license agreement was terminated. He moved in Lousiana state court for a declaratory judgment of breach on the basis that Grill Holdings altered the trademarks without consent, sublicensed the trademarks without first providing notice, failed to pay royalties, and failed to provide financial statements. The trial court cancelled the license agreement and the appeals court affirmed.

While the lawsuit over the license agreement was pending appeal, the Shwartz entities sued the Kohdr entities for trademark infringement and the Kohdr entities sued for a declaration of ownership of the trademarks. Kohdr’s theory was that it acquired ownership of the trademarks in the Bill of Sale.

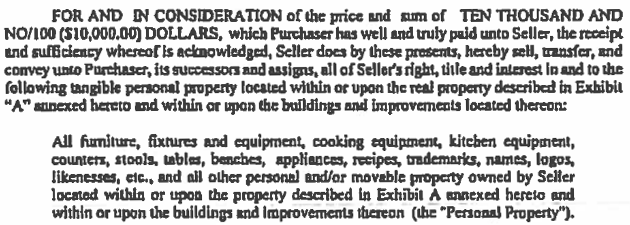

Recall that while the license agreement was with Grill Holdings, the Bill of Sale was with Uptown Grill, selling the following:

If you can’t read it, for $10,000 the Bill of Sale transfers:

[I]nterest in and to the following tangible personal property located within or upon the real property described in Exhibit “A” . . . and within or upon the buildings and improvements located thereon:

All furniture, fixtures and equipment, cooking equipment, kitchen equipment, counters, stools, tables, benches, appliances, recipes, trademarks, names, logos, likenesses, etc., and all other personal and/or movable property owned by Seller located within or upon the property described in Exhibit A annexed hereto and within or upon the buildings and improvements thereon.

Uh oh. While the Bill of Sale is for “tangible personal property,” there it is, undeniably—sale of the trademarks.

All of Shwartz’s efforts to undo what is plainly written failed. Despite the fact that the transferred property was “tangible” personal property, and a trademark is intangible, “in the interpretation of contracts, the specific controls the general.”

The bill of sale didn’t recite the assignment of goodwill, but

Courts have not required that contracts transferring ownership of trademarks explicitly mention the good will of the marks…. The Shwartz parties correctly note that trademarks may not be transferred without the good will of the business to which they are attached; they may not be sold in gross. The Shwartz parties go further, however, and seem to argue that good will cannot be transferred without its express mention in the contract. This argument misses the point…. The Bill of Sale transferred every single asset of Camellia Grill to Uptown Grill. It is clear to this Court that Camellia Grill was sold lock, stock, and barrel. Pursuant to well-settled trademark law, the Court must conclude that the good will of Camellia Grill was transferred with the sale of the entire business.

And the last gasp, in Louisiana a court can consider extrinsic evidence where he literal interpretation leads to an absurd result. Here, the theory is that the $1,000,000 price tag on the license agreement and the $10,000 paid for the personal property, including the trademarks, are irreconcilable, producing an absurd result. But

This fact alone does not render a result “absurd.” The Fifth Circuit has cautioned that, “although a business decision may be unwise, imprudent, risky, or speculative, it is not necessarily ‘absurd.’ We decline to allow contracting parties to escape the unfortunate and unexpected, though not objectively ‘absurd,’ consequences of a contract by subsequently characterizing their consequences as ‘absurd.’”

The License Agreement also didn’t alter or modify the terms of the Bill of Sale. First, the court couldn’t look at the License Agreement to interpret the Bill of Sale because the Bill of Sale was clear and unambiguous and the License Agreement extrinsic evidence. Second, a subsequent license agreement with a different party couldn’t be used to modify the Bill of Sale.

So that’s all expected, but now we get to the part that has me scratching my head. After concluding that Uptown Grill acquired the trademarks in the Bill of Sale, the question remained whether it was just the trademark for the Carrolton Avenue location or elsewhere too. The Bill of Sale was for property “within or upon” the premises:

As outlined in this Order, the Bill of Sale clearly and unambiguously transferred the Camellia Grill trademarks to Uptown Grill. The Court has not been presented with any evidence indicating that Uptown Grill has divested itself of the trademarks. Accordingly, the Court concludes that Uptown Grill owns the trademarks “within or upon” the Camellia Grill location on Carrollton Avenue. The Court will separately issue a judgment in accord with this finding.

Having determined that Uptown Grill has carried its burden to prove that it owns the trademarks, the secondary issue for this Court to address is whether the trademarks transferred to Uptown Grill in the Bill of Sale could be limited to the trademarks “within or upon” the Carrollton Avenue location. In other words, did [Shwartz] retain any interest in Camelia Grill trademarks following the Bill of Sale?

The court concludes “no”:

It is axiomatic that “ownership of trademarks is established by use, not by registration.” Indeed, even if one acquires ownership of a mark, he only acquires ownership of that mark within the geographic area in which he is currently using the mark. At the time of the Bill of Sale, [Shwartz] owned the rights to the Camellia Grill trademarks to the extent of its use of the marks.

As mentioned above, there is absolutely no dispute that, [Shwartz] used the marks solely in connection with the Carrollton Avenue Camellia Grill restaurant. Indeed, at oral argument, counsel for [Shwartz] conceded that the marks had never been used outside of the Carrollton location. The Bill of Sale unambiguously transferred ownership of the marks associated with the Carrollton Avenue location to Uptown Grill. Because [Shwartz] only owned the marks in connection with the Carrollton Avenue Camellia Grill restaurant and those marks were sold in the Bill of Sale, the Court must conclude that [Shwartz] divested itself of all of its interest in the Camellia Grill trademarks.

Well hold on Nelly—what about nationwide rights appurtenant to a federal trademark registration? Have we forgotten about the Dawn Donut rule, “§ 1072 affords nationwide protection to registered marks, regardless of the areas in which the registrant actually uses the mark”? Dawn Donut Co. v. Hart’s Food Stores, Inc., 267 F.2d 358, 362 (2d Cir. N.Y. 1959). Uptown Grill may own the trademark “within or upon” the premises, but Shwartz had greater trademark rights than that—nationwide. Construing the sale of rights “within or upon” a single address to also be an assignment of rights nationwide is, in my view, too far a stretch. Understanding this distinction also makes it much easier to reconcile $10,000 for the assignment of the trademark at the Carrollton Avenue address with a $1,000,000 licensing agreement that includes the right to sublicense the trademarks nationwide.

Yup, wrong.

Uptown Grill v. Shwartz, No. 12-6560 (E.D. La. July 9, 2015)

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Leave a Reply