Every patent litigation starts with an examination of the chain of title, or at least it should. Often there are multiple inventors; every link for each one has to be there, and even the language of the employment agreement has to be just right. Even after that, every corporate assignment has to be done properly.

In Advanced Video Technologies, LLC v. Blackberry Limited, we have three inventors on a patent for a “Full Duplex Single Chip Video Codec.” The court outlined a number of conveyances in the chain of title, but there was one in particular that sealed the fate of the plaintiff.

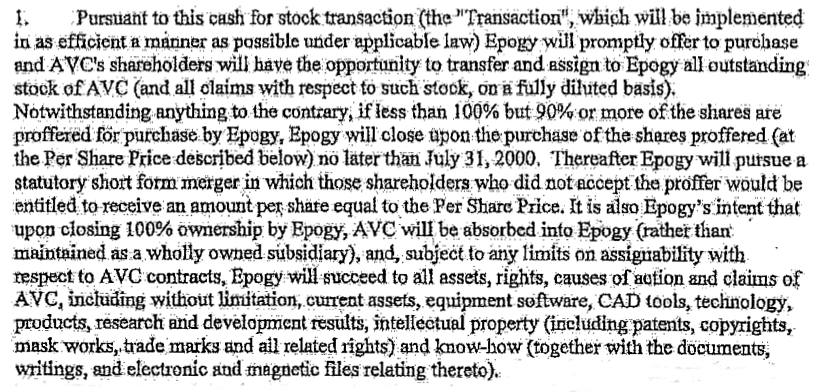

One of the interim patent owners, AVC Technology, Inc., agreed to be purchased by Epogy Communications, Inc. The Purchase Offer Agreement provided that Epogy would purchase 90% or more of AVC and then do a statutory short-form merger:

Epogy thereafter acquired 100% of the AVC shares but never effectuated the statutory short form merger. AVC was dissolved and 2½ months later Epogy assigned the patent, which ultimately ended up in the hands of the plaintiff.

So who owns the patent?

At first, AVT claimed that the patent rights were transferred when AVC was merged into Epogy in a short-form statutory merger. AVT now concedes that no such merger ever took place.

Instead, AVT now argues that no short-form merger was needed, because Epogy acquired AVC’s assets (including its interest in the ‘788 patent) because Epogy purchased all of AVC’s stock before AVC dissolved. AVT cites no authority for this assertion, and understandably so, because Epogy did not acquire any of AVC’s assets simply by purchasing 100% of its stock. That is a well-settled proposition of corporate law in both Delaware (where AVC as incorporated) and California (where Epogy was incorporated)….

So AVT insists that Epogy acquired ownership of the ‘788 patent from its wholly-owned subsidiary incident to AVC’s dissolution. Citing Del. Code. Ann. tit. 8, § 281(b), AVT states that, “it is black letter law that any assets remaining when a corporation is dissolved are to be distributed to stockholders.”…

The problem with this argument is it misconstrues the way Delaware corporate law works.

When a Delaware corporation files a certificate of dissolution, it does not simply evaporate. Rather, it “dissolves” only for the purpose of continuing to do business. By operation of law, Del. Ann. Code §278, the corporation remains continues [sic] in existence for a period of at least three years from the date of dissolution — more, if the period is extended by the Court of Chancery — for the limited purpose of allowing it to wind up its affairs. To that end, it can sue and be sued, dispose of or convey its property and discharge its liabilities. Only after all of that is done is a Delaware corporation permitted “to distribute to their stockholders any remaining assets” — that is, any assets that remain after satisfaction of all liabilities — pursuant to §281(b). Under § 281, stockholders are last in line; they are entitled to receive, not all the assets of a dissolved corporation, but only “remaining assets” — the assets that are left over after all other corporate creditors have been satisfied, or provision made for them to be satisfied….

§281(b) requires that a dissolving corporation or some successor entity adopt a “plan of distribution” of the dissolving corporation’s assets at some time during “the period described in §278” — i.e., the three year statutory wind-down period….

[O]wnership of the assets of a dissolved corporation do not devolve onto shareholders by operation of law immediately upon the filing of a certificate of dissolution; they have to be distributed according to a plan.

So AVC’s assets did not automatically revert to Epogy, its 100% owner, when it filed its certificate of dissolution on November 1, 2002. AVT cites no authority for the proposition that title to AVC’s assets devolved onto its 100% shareholder by operation of law immediately upon the filing of a certificate of dissolution except §281(b), and §281(b) does not so provide.

And therein lies the rub….

Of course, AVC may not have had any obligations or pending claims to settle on the day it filed its Certificate of Dissolution; if so, a plan of dissolution, duly adopted by AVC’s Board, could undoubtedly have provided for a prompt distribution of some or all of AVC’s assets, including its interest in the ‘788 patent. But even on that assumption (and there is absolutely no evidence in the record on the point), AVC and its parent Epogy still had to comply with the statutory formality….

In the absence of a plan, there could have been no distribution on or about November 1, 2002, the date of AVC’s dissolution. And in the absence of a distribution, AVC’s assets, including the ‘788 patent, were not acquired by AVC’s parent corporation, Epogy on November 1, 2002 — or at any time during at least the statutory wind-down period provided for in §278.

Epogy’s purported assignment to the next owner was a mere 2½ months after AVC’s dissolution, so at that point in time Epogy could not have owned the patent it supposedly conveyed. Case dismissed.

The case also has an interesting (to me, anyway) discussion of the assignment of an employment agreement. The patent-in-suit was not filed by the original employer, but by a successor. At least one of the inventors had a duty to assign inventions to the original employer. The original employer gave a security interest in its “Receivables,” which included “Accounts, Instruments, Documents, Chattel Paper and General Intangibles (as defined in the Uniform Commercial Code) …” The Uniform Commercial Code defines “General Intangibles” as “any personal property, including things in action, other than accounts, chattel paper, commercial tort claims, deposit accounts, documents, goods, instruments, investment property, letter-of-credit rights, letters of credit, money, and oil, gas, or other minerals before extraction. The term includes payment intangibles and software.” The court held that the employment agreement was a “General Intangible” and therefore it was acquired by the securing party when the securing party eventually seized the pledged assets. One of the co-inventors then purchased the pledged assets, transferred them to his company, and his company thereafter filed the patent application. By this time the inventor refused to cooperate, but the company showed to the satisfaction of the Patent Office that it owned the patent and successfully prosecuted it without her signature on a formal assignment. The assignment by this inventor was also challenged, but the court did not need to decide whether it was valid in light of the failure of the Epogy assignment.

Advanced Video Technologies LLC v. Blackberry Limited, No. 11 Civ. 06604 (S.D.N.Y. April 28, 2015).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Leave a Reply