Sometimes I find great dissonance between the application of trademark law and the marketplace realities. The parties line all their legal ducks up in a nice straight row, but there’s just such an inconsistency between what the legal outcome is and what consumers’ understanding of the situation might be.

E & J Gallo v. Proximo Spirits, Inc. is that kind of case. Plaintiff Gallo contracted with Tequila Supremo, a tequila supplier in Mexico, to produce a tequila that would be sold under the brand name “Familia Camarena.” Tequila Supremo filed three trademark applications that contained the word “Camarena” in them, CAMARENA, FAMILIA CAMARENA and FAMILIA CAMARENA 1761. Gallo, however, filed trademark applications for the shape of the bottle that would be used for the tequila:

Both Gallo and Proximo Spirits moved for summary judgment on a counterclaim that the Gallo and Tequila Supremo trademark applications and registrations were void for fraud. The theory is this: because Gallo is merely a distributor of the tequila and Tequila Supremo insures the quality of the tequila, Gallo cannot be the owner the bottle marks. The theory against Tequila Supremo is – well, since defendant Proximo Spirits repeatedly said that Tequila Supremo controlled the quality of the tequila there wasn’t a theory, so the court denied the counterclaim as to Tequila Supremo.

Proximo Spirits argued that the fraud was based on a false statement in the declaration, which was that Gallo was the sole source of the tequila, manufactures the tequila, or controls the quality. But there are no statements like that in the application, rather one only avers that it is the owner of the applied-for mark. As a consequence,

| Accordingly, Counterclaimants fail to carry their heavy burden to establish that Gallo expressly misrepresented in its applications that it was the sole source of Camarena Tequila.

…. Counterclaimants’ “sole source” theory appears to be based on outdated trademark law. Although a trademark originally indicated the source of the related product, trademark law has shifted to recognize various valid premises upon which a person or entity may own a trademark, including the control of a product’s quality:

Siegel v. Chicken Delight, Inc., 448 F.2d 43, 48–49 (9th Cir.1971). Because of this changing rationale and growth in the practice of trademark licensing and franchising, a trademark is not necessarily an indicator of source. Indeed, a trademark may denote source, control of quality, and good will, among other things. Moreover, it is not uncommon to see marks of more than one company appearing on or denominating a single product or service. The marks of different companies may appear on a single product where they serve separate functions such as “manufacturer/distributor” or “licensor/licensee.” Accordingly, and contrary to Counterclaimants’ arguments, a trademark does not necessarily designate the source of the goods or services with which it is associated. Viewed under this legal perspective, Counterclaimants’ “sole source” misrepresentation theory fails legally and factually. |

The court also assessed defendant’s theory that Gallo was not the owner of the mark because it was only a distributor and therefore didn’t control the quality of the tequila goods. Gallo successfully deflected the theory on the basis that distributors may, indeed, own trademarks, that the agreement with Tequila Supremo allowed it to own the trademark in the bottle shape, and that it also participated in quality control by inspecting the tequila.

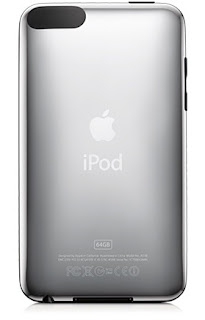

This is all an utterly correct statement of law, but completely misses the point. There are lots of ways that two trademarks can be used on the same goods. There can be a house brand used with a product brand, like a well-recognized Apple logo with the “iPod” word mark:

The court characterized the relationship between Gallo and Tequila Supremo as “co-branding,” but that’s wrong. In a co-branding relationship, the different owners’ use of their respective marks represents different types of relationship with the goods or services. When we see Edy’s Nestlé Butterfinger ice cream we know that Edy’s makes the ice cream and the Butterfinger is a component of the ice cream. When we see “Mercedes Benz Fashion Week,” we don’t think that Mercedes Benz has gone into the fashion or the trade show business, but rather that it paid to a lot of money to have high exposure for its brand so it could ultimately sell more cars.

Where this case went off the rails is that the court didn’t examine whether the use of the marks was consistent with what a consumer might think about the message conveyed by that use. As consumers, we think that the label on the bottle and the bottle itself are from the same source, that is, that both trademarks, the label and the bottle, are conveying the same relationship-type information. So something is fundamentally wrong if you can say that two trademarks providing the same information – in this case “I am the source” – can be owned by two different entities.

As proof, imagine the label and bottle shape are disconnected. In that case, because a product packaging or configuration mark is very weak, we will soon assume that the bottle shape is not an indicator of source. Imagine if the Coke bottle was licensed for use for a coffee drink by a different company – how long would it take before we don’t think of it as standing for “Coke” anymore? If Gallo had established the bottle as its trademark by its exclusive use across a number of its products, so we had learned that the bottle shape means “Gallo” regardless of the liquid inside – the house mark/product mark relationship – the outcome might be different. But that’s wasn’t this case.

I think the defendant had the correct view of what consumers would think, i.e., no consumer would think that the shape of the bottle and the name of the brand on the label are indicators of different source. But the defendant could find no hook in the law that supported that theory. I’m hoping for an appeal.

E & J Gallo v. Proximo Spirits, Inc., No. CV-F-10-411 LJO JLT (E.D. Cal. Jan. 30, 2012).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.