Judge Alsup from the patent-heavy Northern District of California court has taken advantage of the almost certain appeal of patent cases by writing an “Appendix” to point out what he perceives as an unfairness in patent jurisprudence. He asks the Federal Circuit to address the burden of proof in swearing behind references.

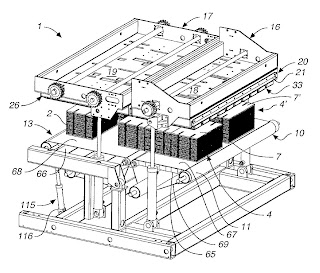

The patent in suit was for an improvement in bundle breakers, which are machines that break stacked sheets of materials along scored lines, like for cardboard boxes. By the plaintiff’s admission an existing machine had every limitation of the patent, so the only question was whether the machine was prior art. It was sold in June, 2002 and the patent application was filed on August 28, 2002, so the patent owner had to come forward with evidence demonstrating that the inventor conceived of the patented invention before June, 2002.

The court ultimately held that the patent was invalid for obviousness based on other references. It took the opportunity, though, to comment on the burden of proof for swearing behind a reference. The court was clearly troubled by the amount of evidence that the plaintiff was able to rely on for swearing behind the earlier machine, just a lab notebook and oral evidence (presumably from the person who kept the lab notebook).

In 1935, it was the patent owner who had to prove, by clear and convincing evidence, that the true invention date was earlier than the presumptive invention date, the date of the application:

When the invention date is due to be carried back beyond his application, courts regard the effort with great jealousy, and must be persuaded with certainty which is seldom demanded elsewhere; quite as absolute as in a criminal case, in practice perhaps even more so.

United Shoe Mach. Corp. v. Brooklyn Wood Heel Corp., 77 F.2d 263, 264 (2nd Cir. 1935). (As an aside, this is currently the standard when a trademark owner has to prove it had an earlier date of first use than what was stated in its trademark application. McCarthy § 19:52).

The court explained, though, that based on current Federal Circuit precedent the burden is now on the challenger to prove invention date by clear and convincing evidence, no matter whether it has to prove that a piece of invalidating art was invented before the patent, or that the invention described in the patent was not before the invention of the invalidating art.

The court pointed out that in the latter case, there are reasons the challenger should not have such a heavy burden. First, the invention date is a fact question rarely examined during the prosecution of the patent, so the court felt it should not entitled to the same degree of deference. Further, where the challenger has to prove that the patent was not invented before the invalidating art, the accused is in the position of proving a negative, i.e., that invention did not happen at a certain point in time. There is a difference of authority on how much evidence the patentee must provide to prove its invention date (minimum evidence, as in Apotex USA, Inc. v. Merck & Co., Inc., 254 F.3d 1031, 1037-38 (Fed. Cir. 2001) or corroborated evidence of conception, as in Mahurkar v. C.R. Bard, Inc., 79 F.3d 1577 (Fed. Cir. 1996)), but certainly not as much proof as required when the accused infringer has to prove the positive, that an invalidating reference was invented before the filing date of an application. The court concluded:

It is true that the Patent Act presumes the validity of all issued patents and places the burden of invalidating them on the challengers. Once a challenger does so, however, it is respectfully submitted that the challenger should not have the further burden to disprove a patentee’s suggestion (based on merely enough evidence to defeat summary judgment) of an even earlier invention date, much less to prove the negative by clear and convincing evidence. Rather, once the challenger has proven, by clear and convincing evidence, the existence of anticipatory prior art earlier than the presumed date of invention (the filing date), the burden of persuasion should rest on the patentee to “swear behind” the anticipatory art.

Geo. M. Martin Co. v. Alliance Machine Sys. Intl, LLC, No. C 07-00692 WHA, 2008 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 95700 (N.D. Cal. Nov. 17. 2008).

© 2008 Pamela Chestek