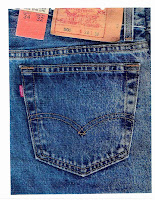

Not surprisingly, Levi Strauss & Co. v. Abercrombie & Fitch Trading Co. is a case about enforcing the “arcuate” pocket stitching design on Levi’s jeans. Levi’s is not one to be meek in enforcing its registered trademark, shown below:

But it’s butting up against a litigious player in its own right, Abercrombie & Fitch (various dockets here, commentary here, here and here), a company that has itself sued on its own jeans pocket design (here).

But it’s butting up against a litigious player in its own right, Abercrombie & Fitch (various dockets here, commentary here, here and here), a company that has itself sued on its own jeans pocket design (here).

Abercrombie filed an intent to use trademark application, and started using, this mark for an exclusive line of clothing sold under the “Ruehl” brand:

On a motion for summary judgment Abercrombie attacked the validity of the Levi’s trademark, claiming both that the mark is weak and raising a formal abandonment defense. Abercromie doesn’t shirk on the evidence, but bases no small part of its defense on evidence arising from Levi’s previous lawsuits and other enforcement efforts. Most of it fails on evidentiary grounds.

Abercrombie tried to use Levi’s past settlement agreements as proof that pocket designs are in a crowded field and thus the Levi’s mark is not strong, or even weakened to the point of abandonment. But the settlement agreements were not admissible under Fed. R. Evid. 408, which excludes evidence offered to prove liability for, invalidity of, or the amount of a claim that is disputed.

This is an interesting tactical point, though. Levi used evidence of its enforcement efforts to support its argument that the mark is not weak, stating “LS&CO. spends enormous resources to preserve its mark and maintain a zone of protection against similar uses that would erode its distinctiveness. The Supplemental Declaration of Thomas Onda, submitted with this opposition, shows a few examples among hundreds of enforcement actions taken in furtherance of this effort.” So Levi may use the evidence to prove its own case, but Abercrombie is barred by Rule 408 from using similar evidence to disprove the same point.

Abercrombie also refigures survey evidence from old cases to try to demonstrate that the Levi mark is losing strength over time, but does it through attorney argument rather than expert testimony. These surveys also therefore inadmissible.

Although the evidence is excluded, the court makes it clear that the evidence wouldn’t have helped Abercrombie on its abandonment defense:

To support its claim for abandonment, Abercrombie primarily relies upon the third party settlements and the surveys from other litigation, which the Court has excluded. However, even if the Court were to consider this evidence, it would not alter the Court’s conclusion. It is possible that the presence of other jeans manufacturers using designs purportedly similar to the Arcuate mark has impacted the commercial strength of that mark. See, e.g., Adidas-America, Inc. v. Payless Shoe Source, Inc., 546 F. Supp. 2d 1029, 1078 (D. Or. 2008) (noting that “third party uses of [allegedly similar] designs is relevant to the strength of the mark, not abandonment”). However, only when all rights of protection have been lost can a party be found to have abandoned its trademark.

Dr. Sood’s survey, however, establishes that notwithstanding the presence of third parties using purportedly similar designs, the public still recognizes the Arcuate mark as a source indicator for Levi’s brand jeans. Abercrombie has not put forth admissible evidence that rebuts Dr. Sood’s conclusions. Accordingly, the Court concludes that Abercrombie has failed meet its strict burden of proof and has failed to put forth facts from which a reasonable jury could conclude that the Arcuate mark has lost all significance as a mark. LS&CO is entitled to judgment in its favor on this aspect of Abercrombie’s counterclaim. For these same reasons, LS&CO is entitled to judgment on Abercrombie’s affirmative defense of abandonment.

Summary judgment on the abandonment defense granted in favor of Levi. But, the court acknowledged that there was nevertheless a question about the strength of Levi’s mark because of the co-existence:

[M]any of the articles that LS&CO submits to show third party recognition of the Arcuate mark are dated. Indeed, of the nine articles submitted, only one appears to have been published in this decade. Abercrombie also introduces evidence that there are numerous third parties using designs that are purportedly similar to the Arcuate mark. Finally, although the Court has concluded that Abercrombie has not established a genuine issue of material fact to show the Arcuate mark has lost all significance as a mark, the Court concludes that Dr. Ford’s criticisms of Dr. Sood’s consumer recognition survey may bear on the issue of whether LS&CO can show the mark is “famous” for purposes of its dilution claim.

The TTAB has stated that it was “reluctant” to find the Arcuate mark famous on a record that appears similar to this case. See Levi Strauss & Co. v. Vivat Holdings PLC, 2000 TTAB LEXIS 817 (Dec. 19, 2000). In light of third party usage of purportedly similar marks, the lack of specific figures for advertisements bearing only the Arcuate mark, the age of the materials regarding third party recognition, and the survey evidence, the Court concludes that there are facts from which a reasonable juror could reach a determination in either party’s favor on the question of fame.

Abercrombie’s motion for summary judgment on the absence of dilution and noninfringement denied since questions of fact remained.

Levi Strauss & Co. v. Abercrombie & Fitch Trading Co., No. C. 07-03752, 2008 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 87625 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 16, 2008).

© 2008 Pamela Chestek