Movie deals are made at the Sundance Film Festival, and they’re made fast. Weinstein Company v. Smokewood Entertainment Group gives us some of the flavor.

The film was “Push,” now renamed “Precious.” (One blog suggests that it was done to avoid confusion with a cheesy sci-fi film of the same name.) Push won the Grand Jury Award and the Audience Award at the Sundance Film Festival, as well as the Audience Award at the Toronto film festival. Here’s the trailer – be forewarned, it’s brutal material:

The film is being distributed by Lionsgate, but The Weinstein Company (TWC) had been negotiating at Sundance for the rights. TWC claimed that on January 27, 2009 it received an oral offer for exclusive distribution rights from Cinetec Media, Inc., acting as agent of Smokewood Entertainment Group, the defendant. TWC says it accepted the offer orally, and that Cinetec was to provide the written agreement. This email exchange was later that day and the next:

[6:29 pm, from TWC]

Dear John and Bart: I am pleased to confirm on behalf of the Weinstein Company LLC that we have accepted the terms of your last proposal made by you during our breakfast meeting this morning and our subsequent telephone conversation with respect to the acquisition of the exclusive worldwide distribution rights in and to the feature film presently entitled “Push”: based on a novel by Saphire” [sic]. Our attorneys are drafting a customary deal memorandum consistent with the terms we agreed upon and will be forwarding to you shortly.We are pleased to have concluded this deal, as it has been an incredible journey to get here and appreciate all your efforts.

[6:37 pm, from Cinetec]

Gentlemen-Since our last conversation, I have been on a call with the producers and financiers explaining every sentence. I will call you after. Not being at the breakfast, I don’t know exactly what was discussed there, but am relaying the contents of our conversation this afternoon. Will call asap. Best, bw

[7:05 pm, from TWC]

Bart: Thank you for all your hard work on this title. I just got off the phone with Harvey [Weinstein] and I am glad to confirm that we have a deal. Additionally, we will work with you to accommodate your additional needs (i.e. Elephant Eye).

Best regards,

[7:12 pm, from Cinetec]

Guys, I’m explaining every detail to the producers and financiers and taking comments and will call you when this conversation is over. Best, bw

[2:04 am on January 28, 2009, from TWC]

Earlier today, we accepted all of the terms and conditions of your offer, thereby closing a deal to acquire the rights to the film entitled ‘Push’. . . . [We have been] awaiting the written documentation of our deal [and] . . . fully intend to enforce the deal . . . with or without written documentation.

[4:42 am, from Cinetec]

[There had] been no agreement reached . . . [and there were several] [e]ssential points [that] had not and have not been agreed, including, without limitation, the division of profits between Weinstein and our client, and whether or not rights in the international territories could be granted. . . . [A]ll points under discussion with Weinstein were subject to explanation to and review by our clients and their counsel.

[4:50 am, from TWC]

[Your e-mail] constitute[d] a repudiation of the agreement which we definitely did reach. |

On February 2, Lionsgate, Smokewood and Cinetec announced that Lionsgate would be the distributor of the film. Two days later, TWC sued.

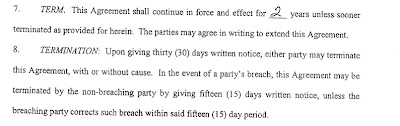

Smokewood brought a motion to dismiss the complaint. TWC advanced four theories for why it should get to distribute the film – breach of agreement for exclusive license to distribute the film (oral or written), breach of oral agreement for non-exclusive license to distribute the film, and breach of binding preliminary commitment to negotiate in good faith. None were successful.

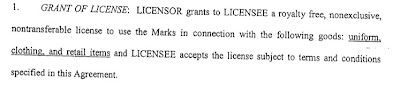

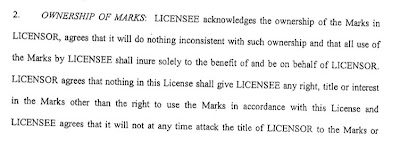

First, on the oral exclusive license, it’s black letter law that an exclusive license has to be in writing, so that argument failed. On the written agreement theory, TWC argued that the above email exchange was a written agreement to license the film. The court noted that it’s only TWC that believes there is a firm deal, not Smokewood. Further, the emails don’t have any terms of the deal and lack a suggestion of finality. Even under the liberal standards on a motion to dismiss, this wasn’t good enough.

On the oral non-exclusive license theory, the court held that an oral non-exclusive license may only be found in the narrow circumstances where one party created a work at the other’s request and handed it over, intending that that other copy and distribute it. That clearly wasn’t the case here; Push was complete before TWC ever entered the scene. The court didn’t think much of the argument, either:

| Plaintiff’s position in this case seems to be that a nonexclusive license should function as a sort of consolation prize for TWC’s failure to successfully secure an exclusive license. The cases cited by plaintiff do not support this argument, which, if accepted by the Court, would undermine copyright owner’s statutory rights by turning every failed negotiation for an exclusive license into a potential claim for a non-exclusive license. |

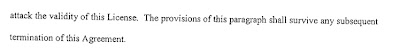

Finally, on the failure to negotiate in good faith, under New York law there can be a breach of a binding preliminary commitment to negotiate in good faith where open terms remain but the parties have agreed on certain important ones and have agreed to bind themselves to work out the remaining terms. It’s a narrow doctrine – “It is fundamental to contract law that mere participation in negotiations and discussions does not create binding obligation, even if agreement is reached on all disputed terms.” Further, “[t]here is a strong presumption against finding binding obligation in agreements which include open terms, call for future approvals and expressly anticipate future preparation and execution of contract documents.” The five factor test wasn’t met in this case.

NPR’s “Morning Edition” story “Oprah, Tyler Perry And A Painful, ‘Precious’ Life.”

Coming to theaters in November.

The Weinstein Co. v. Smokewood Enter. Group, LLC, No. 09 Civ. 1972 (NRB), 2009 WL 3097201 (S.D.N.Y. Sep. 25, 2009).

© 2009 Pamela Chestek