I recently reported on a case where the plaintiff successfully claimed that a trademark hadn’t been assigned, despite the fact that virtually all of the other assets of the company were assigned. Jomaps, LLC v. D-Mand Better Products, LLC is the opposite case.

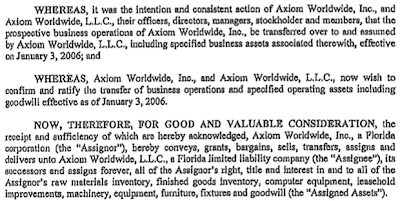

The principle is that the assignment of a business in its entirety generally includes an assignment of the trademark, even if not expressly listed as an asset. This makes a lot of sense; think of all the small businesses — restaurants, boutiques, plumbers, cleaning companies — where no one really realizes that they have a trademark asset. They sell the business, no trademark is mentioned, but generally the intent is to sell the name, too.

In Jomaps, an unrelated company, Jomaps, Inc., sold its assets, including the M-1 mark for mildewcide products, to Orr Enterprises, LLC. Orr Enterprises then changed its name to Jomaps LLC.

In Jomaps, an unrelated company, Jomaps, Inc., sold its assets, including the M-1 mark for mildewcide products, to Orr Enterprises, LLC. Orr Enterprises then changed its name to Jomaps LLC.

The owner of the new Jomaps, Wayne Orr, defaulted on his payments to Jomaps, Inc. and so defendant D-Mand rescued Jomaps by buying out the company. Whether the trademark was transferred is the question; Orr claims that the trademark was “carved out” of the transaction and instead he only granted temporary permission, revokable without notice, to D-Mand to use the mark. Interestingly, it doesn’t appear that there is any overarching transactional document for the acquisition of the business.

I won’t list all of the evidence that D-Mand produced about the transaction, but it was extensive. Cash, receivables, employees, and insurance policies were transferred to D-Mand. The formula for the mildewcide, a trade secret, was transferred. Orr himself worked for D-Mand for two years before he filed the suit and he even signed an application for financing for D-Mand that included the trademark as a secured asset.

The court summarized the case:

| D–Mand has produced copious records to show the transfer of all of the assets from Jomaps to it. It contends without dispute that it possesses the trade secret formula for the M–1 mildewcide at issue, and no trade secret claim is in the case. It has shown that Jomaps was left as a shell with nothing and no operations, manufacturing nothing, selling nothing, and doing nothing. Moreover, the record indicates that Orr and his counsel were representing to third parties that Jomaps was defunct.

It makes little sense to have transferred everything in the Jomaps company to D–Mand, including the goodwill, payables and other obligations, without having conveyed the trademark. The evidence shows that Jomaps went out of business for some time and other than filing a 2012 registration, is not operating now. |

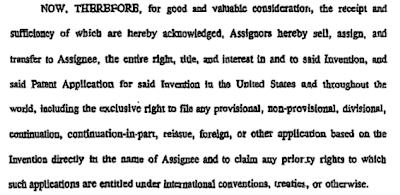

All that Orr could come up with was — no small thing — the statutory requirement that “assignments shall be by instruments in writing duly executed.” Lanham Act § 10, 15 U.S.C. § 1060. The court readily disposed of the argument, though:

|

[T]he “writing” requirement of the Trademark Act has been on the books since at least 1905. Since then, many cases, including a case decided by the old Fifth Circuit which is very similar to the instant case, have held that even without a formal writing, the transfer of all of the assets of a company to another, including the goodwill, means that the trademark in question has been transferred as well. Holly Hill Citrus Growers Ass’n v. Holly Hill Fruit Products, Inc., 75 F.2d 13, 14–15 (5th Cir.1935) [and others]. This Court understands the wisdom in these cases because sometimes a transfer of assets is simply not neatly bundled up with copious documentation prepared by lawyers and scriveners. But if the transfer really took place, there is no sense in invalidating the transfer of the trademark and shutting down the business of an obvious transferor [sic, transferee].

|

(Brackets mine). Motion for preliminary injunction denied.

As an aside, I don’t see anything in the decision explaining why Jomaps LLC has standing for a Lanham Act claim. Jomaps alleges that Count 1 of its Amended Complaint is for “Trademark Infringement.” But a Lanaham Act infringement claim, whether under § 32 or § 43(a), require proving likelihood of confusion. The decision says that Jomaps can’t even make a competitive product, so it’s not clear to me how there can be two products that might be confused.

Jomaps, LLC v. D-Mand Better Prods., LLC, No. 1:12-cv-01376-TWT (N.D. Ga. July 23, 2012).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.