It’s always tricky to sell a business that uses your personal name. Probably a lot of the value of the acquisition is tied to the name — imagine selling Martha Stewart Living Omnipedia without getting full rights to the name “Martha Stewart.”

But the person selling the name has made his or her living in the industry and, understandably, isn’t going to want to altogether give up the right to use his or her own name for a future business. Yet the acquiring company isn’t going to be too happy having to compete with, essentially, itself reformed. So you can see the tension in trying to craft the document that describes how the seller can use his or her name in the future.

One example of how it played out was in JA Apparel Corp. v. Abboud (blogged here). In it, Joseph Abboud sold the trademark rights in his name but the trial court, on remand, ultimately decided he could use his own name for his new “jaz” brand as long as the use of his name was a fair use, that is “otherwise than as a mark.” Lanham Act § 33, 15. U.S.C. § 1115.

We now have a similar situation in JL Powell Clothing LLC v. Powell — the caption is already a giveaway. Powell ultimately sold his business and started a new business under the name “The Field.” On the front cover of the catalog it said “In the Salt: Dispatch—J. Powell” and inside the front cover was a photograph of Powell and a message to customers signed “Josh Powell.”

The Contribution Agreement Powell had signed said this about Powell’s future use of the JL Powell mark and name:

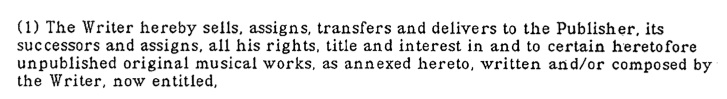

If you can’t read the image, it says:

In connection with this Agreement and the transfer and assignment by JLP of all JLP Intellectual Property to [JL Powell LLC], Joshua L. Powell, (the “Founder ”) hereby grants to [JL Powell LLC] throughout the world the sole and exclusive right, license, and permission to use his name and endorsement to exploit, turn to account, advertise, and otherwise profit from [JL Powell LLC’s] goods and services bearing such name, image, and/or endorsement. The grant made hereunder shall be exclusive to [JL Powell LLC], and the Founder agrees that he shall not, on behalf of himself or any other person or entity, grant any similar right of any kind in connection with any business competitive in any respect with [JL Powell LLC] or any of its affiliates and/or subsidiaries. The Founder further agrees that he will not use his name or permit any other person or entity to use his name, and otherwise will not assert any right to use his name, including but not limited to any right to use his name under the doctrine of fair use, in connection with any business competitive in any respect to [JL Powell LLC] or any of its affiliates and/or subsidiaries.

Powell made unsuccessful contract-based arguments trying to undo the effect of this clause, but the agreement successful wrote around the fair use defense:

Section 7.1(b) of the Contribution Agreement is broader than the agreements at issue in Madrigal and Abboud. In Section 7.1(b) Powell grants the exclusive use of his name and agrees not to use his name or permit any other person or entity to use his name in connection with any business competitive in any respect to JL Powell LLC or any of its affiliates and/or subsidiaries. Powell’s grant in Section 7.1(b) goes beyond the conveyance of trademarks or trade names. Section 7.1(b)’s contemplation of the trademark concept of “fair use” itself adds support to the conclusion that Powell was conveying the use of his personal name in addition to a trade name. “In technical trademark jargon, the use of words for descriptive purposes is called a ‘fair use,’ and the law usually permits it even if the words themselves also constitute a trademark.” By agreeing not to assert a fair use defense, Powell is essentially giving up his right to use his name, even for descriptive purposes, in connection with any business competitive with JL Powell LLC and its affiliates and subsidiaries.

(Emphasis in original.) Powell therefore breached the agreement by using his personal name for his new business and the court granted a preliminary injuction.

JL Powell Clothing LLC v. Powell, No. 2:13-CV-00160-NT (D. Maine Jan. 30, 2014).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.