While I write about all the intellectual property disciplines, I have a soft spot for trademark ownership disputes. And I was, frankly, surprised by today’s case—it was not the outcome I expected when I first started reading.

Tammy Goldthorpe filed an application for the mark SLIPPERY WIZARD for asphalt release agent. The application was opposed by her former employer, Brody Chemical Company Inc.* So you see what this looks like at first, an attempted rights grab by a former employee. Only, turns out, it was Ms. Goldthorpe’s former employer who was making the grab.

You get the gist pretty early in the case with this:

The pertinent portions of Mr. Liddiard’s testimony, Opposer’s primary witness, are directly contradicted by the testimony of Applicant’s five witnesses, including Opposer’s own witness, Mr. Butler. The level of contradiction, culminating in a forged date on a material piece of evidence renders Mr. Liddiard’s testimony utterly unreliable.

Yes, so when your own employees contradict the company’s position, and agree with the former employee’s version of events, it’s not going well for you.

Goldthorpe claimed that she had created the asphalt release and sold it through another company under another name before working for Brody Chemical. When Brody Chemical became interested in selling it, they asked for a new name and she suggested SLIPPERY WIZARD. When Goldthorpe ultimately went to work for Brody Chemical, she claimed to have an oral agreement that she would be paid a dollar per gallon sold by others in the company.

There is so much false testimony by Mr. Liddiard it’s hard to find the best example to give you the flavor of it. But here’s some (sorry for the length, but it’s pretty damning):

Mr. Liddiard testifies regarding the genesis of the name as follows:

Once we decided to add a new product other than our current Asphalt release, we were going to come up with a new name. Well, Asphalt Release, that’s the generic name for it, so we had to come up with something different. And so in a manager’s meeting, as I recall, there was myself, Buzz Butler, and I think that’s it. Just the two of us were in a management meeting, and we were trying to think of a name. And I think it was Buzz that came up with the name. He just said Slippery Wizard, and we went, “okay. That will work as a secondary name for a second product for Asphalt Release.” … She – I didn’t even have a conversation with Tammy about the name for the product. We just decided to add a secondary product. It needed a name to go on the price list, and so we came up with – I came up with a formula, we costed it. I needed a name to put it on the formula – on the price list, so Buzz and I thought of a name by – I still look back, and I think it was Buzz that said Slippery Wizard. And I went, “Yeah, that sounds okay. Let’s go with that.” And we did it.

He further testifies that Ms. Goldthorpe had no involvement in the selection of the SLIPPERY WIZARD name and mark.

This testimony is breathtaking in its “inaccuracy.” As noted above, Mr. Butler testifies that at that time (2004) he was the regional manager in Montana and was not involved in management in the main office. More specifically, he testifies that he did not come up with the name SLIPPERY WIZARD and was in no way involved in the creation or adoption of the name, and that Applicant was the one who came up with the name and that she brought the formula to opposer. He does not remember hiring Applicant. He testifies that employees and customers associated Applicant as the source of the SLIPPERY WIZARD product.

Mr. Liddiard testifies that he “came up with the formula” for the product and Applicant did not give it to him. He testifies that a Mr. Steve Madsen had suggested using cooking grease for an asphalt release agent and Mr. Liddiard, or his company, developed the product. However, Ms. Goldthorpe submitted the assignment agreement she entered into with Mr. Madsen recognizing her invention and ownership of the formula for the asphalt release product. This is corroborated by Mr. Forsgren’s testimony that Steve Madsen and Ms. Goldthorpe “manufactured, sold, delivered asphalt release” in 2003 and that it was Ms. Goldthorpe’s product.

(Internal citations omitted.)

Without any evidence in Brody Chemical’s favor, there isn’t a lot of legal analysis required. Although there was no written agreement until 2011, licenses can be oral. The trademark owner doesn’t have to use the mark itself, the use can be solely by a licensee, with the use inuring to the licensor’s benefit. Even if the Brody Chemical name was on the packaging, a trademark owner is not required to apply its name to the goods. The mark was not designed by the employee in the scope of her employment, but rather she rebranded her product in anticipation of, and actually, receiving royalties for its sale. “The preponderance of the evidence supports Applicant’s position that Applicant owns the mark and Opposer was simply the licensee while Applicant was affiliated with Opposer.” The opposition was dismissed.

HT to John Welch of the inimitable TTABlog for the case.

Brody Chemical Co. v. Goldthorpe, Opp. No. 92104070 (June 5, 2014).

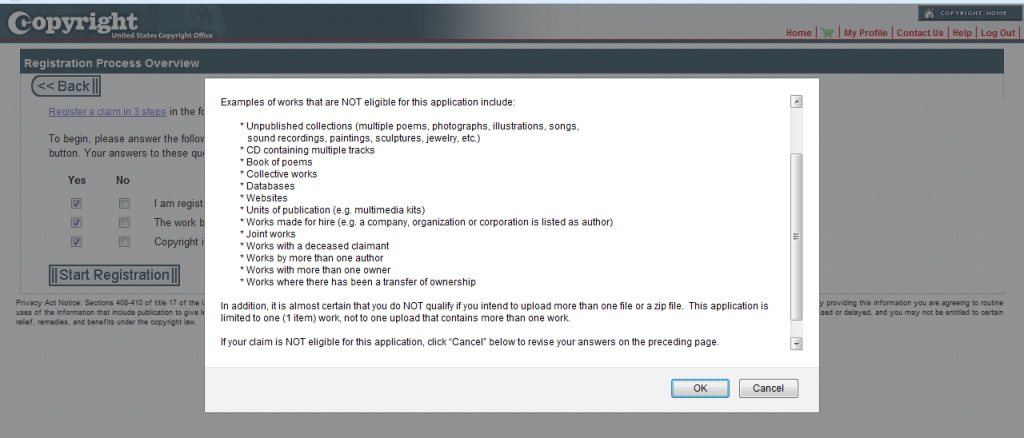

*Seriously Brody Chemical? A paper application in 2011?

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.