Boy, is it hard to write an effective invention assignment for an employment agreement.

First, under US law only a natural person can be an inventor, not a juristic person. When you have an employee whose job is inventing, the solution is to create an automatic assignment to the employer, which is generally done when an employee is first hired. Every employer should know by now to use the words “hereby assigns” rather than “shall assign” in its invention assignment agreements. With “shall assign” the employee has only a duty to assign, so if the employer never follows through with the document the employee will remain the patent owner (and will undoubtedly use the rights in some way adverse to his former employer, causing all sorts of havoc).

But it’s more complicated than that. The legal conclusion that there can be an automatic assignment doesn’t really square with how patents are prosecuted. The patent application has to be filed by the inventor, the natural person. The employer will want the patent prosecution history to reflect the assignment from the employee to the employer. So the employment agreement accommodate this desire too, by obliging the employee to sign all necessary documents and appointing the company as an attorney in fact if the employee refuses to do so.

But wait, there’s more. A number of states statutorily prevent employers from overreaching on a claim of invention ownership. California has typical language:

(a) Any provision in an employment agreement which provides that an employee shall assign, or offer to assign, any of his or her rights in an invention to his or her employer shall not apply to an invention that the employee developed entirely on his or her own time without using the employer’s equipment, supplies, facilities, or trade secret information except for those inventions that either:

(1) Relate at the time of conception or reduction to practice of the invention to the employer’s business, or actual or demonstrably anticipated research or development of the employer; or

(2) Result from any work performed by the employee for the employer.

(b) To the extent a provision in an employment agreement purports to require an employee to assign an invention otherwise excluded from being required to be assigned under subdivision (a), the provision is against the public policy of this state and is unenforceable.

So this limitation finds its way into employment agreements too.

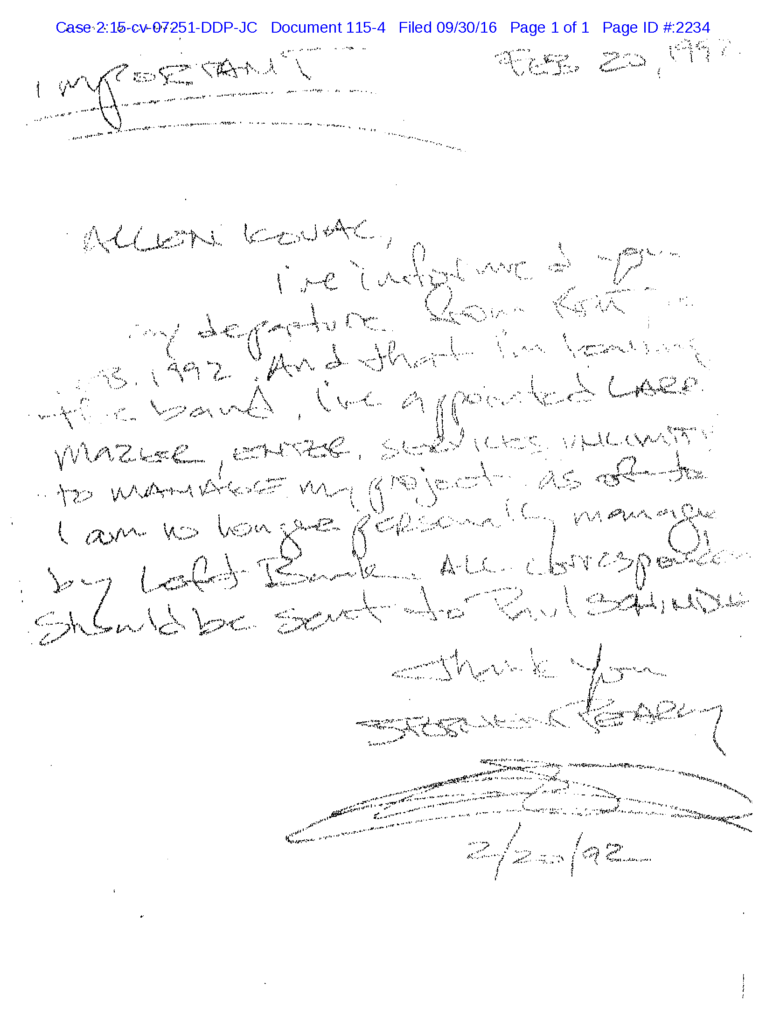

Which brings us to PerdiemCo, LLC v. Industrack LLC. The inventor of the patents-in-suit, Darrell Diem, was employed by a third party, Time Domain, at the time of his invention. Diem had signed an invention assignment agreement with the following language:

I hereby assign to Company my entire right to all the Work Product, which Work Product is and will be the sole and exclusive property of Company; provided however, that I shall not be required to assign to Company any invention that I developed entirely on my own time without using Company’s funds, equipment, materials, facilities or trade secret information except for those inventions that either: (i) relate at the time of conception or reduction to practice of the invention to Company’s business, or actual or demonstrably anticipated research or development of Company, or (ii) result from or are related to or suggested by any Company research, development or other activities, including, without limitation, any work performed by me for Company.

(Emphasis in original.) The agreement also provided that “in the event Employee is required to give testimony or take other actions that require more than, for example, a signature on an assignment document … the Employee shall be compensated on an hourly basis….” and required the an employee “cooperate with Company … in the procurement and maintenance of Company’s rights in Work Product, including, but not limited to, patents and copyrights … [and] sign all papers which Company may deem necessary and desirable for vesting Company … with such rights.” (Ellipses and brackets in original.)

Diem admitted at a deposition that he conceived and developed the inventions claimed in the patents-in-suit while employed by Time Domain. Defendant Geotab therefore challenged PerdiemCo’s ownership of the patents, asserting that they had been automatically assigned to Time Domain by operation of the employment agreement and PerdiemCo therefore did not have standing.

So, was there language of automatic assignment? Check, “Mr. Diem’s Assignment Agreement with Time Domain unambiguously creates an automatic assignment of Mr. Diem’s ‘Work Product.’ ” But the agreement then introduced an ambiguity, by continuing “I shall not be required to assign ….” What exactly was it that didn’t get assigned? Was it all inventions that were independently created, with only a future duty to assign those that nevertheless “relate at the time of conception or reduction to practice of the invention to the Company’s business”? Or instead are those, the ones that that fall into the exception to the exemption from assignment, automatically assigned?

As a “patent” ambiguity in the agreement it was the court’s, not the jury’s, role to construe the meaning of the agreement. The court held that the assignment provision did not automatically assign everything Time Domain was entitled to own, but instead there was only a duty to assign a subset of it:

The Assignment Agreement as a whole suggests that inventions Mr. Diem conceives or develops without using Time Domain’s resources are not automatically assigned to Time Domain. The third paragraph of the Agreement relates to Mr. Diem’s continuing obligations should his employment be terminated. This paragraph provides that “in the event Employee is required to give testimony or take other actions that require more than, for example, a signature on an assignment document … the Employee shall be compensated on an hourly basis ….” The fourth paragraph of the Agreement requires Mr. Diem “to cooperate with Company … in the procurement and maintenance of Company’s rights in Work Product, including, but not limited to, patents and copyrights … [and] sign all papers which Company may deem necessary and desirable for vesting Company … with such rights.

These provisions suggest that certain Work Product is not automatically assigned to Time Domain. If all Work Product automatically transferred to Time Domain, it would be unnecessary for Mr. Diem to sign any paper to vest Time Domain with rights. This interpretation is consistent with the well-established rule of contract construction that any ambiguity in a contract must be construed against the drafter of the contract, which in this case is Time Domain. Accordingly, the Court finds that Mr. Diem’s independent inventions are at most subject to a future obligation to assign, depending on whether those inventions meet the relatedness requirements defined by the Agreement.

(Emphasis in original, citations omitted.) Having decided that there was no automatic assignment of independently created inventions, in this case it didn’t matter whether or not the inventions were related to Time Domain’s business, because the facts were that Time Domain never obtained an assignment.

Well, fudge. The language that the court relied on to decide that something must be subject to a future assignment isn’t there because there was this special subset of inventions, it is just standard belt-and-suspenders language to ensure that the employee cooperates in assigning all inventions. And indeed, the attempt to add language protecting an employee’s interest consistent with statutory law was poorly drafted, and we live and die by our document drafting. I’m not suggesting that the court’s legal conclusion was wrong, but it certainly was contrary to any sensible employer’s intention. Time to go back and re-visit those assigment provisions.

Perdiemco v. Industrack LLC, Case No. 2:15-CV-00727-GRG-RSP, 2:15-CV-0027-JRG-RSP, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 141935 (E.D. Tex. Oct. 18, 2016) (report and recommendation), adopted by Case Nos. 2:15-CV-00727-GRG-RSP, 2:15-CV-0027-JRG-RSP (E.D. Tex. Nov. 1, 2016).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.