Defendant Lingfu Zhang was accused of downloading the movie Fathers & Daughters via BitTorrent. Plaintiff Fathers & Daughters Nevada, LLC was the author and registered copyright owner of the film and sued Zhang. But copyright ownership is tricky.

F&D had a sales agency agreement with non-party Goldenrod Holdings and its sub-sales agent Voltage Pictures.1 Goldenrod and Voltage were given the right, as described by the court, to license most of the exclusive rights in the copyright in the film, including rights to license, rent, and display the motion picture in theaters, on television, in airplanes, on ships, in hotels and motels, through all forms of home video and on demand services, through cable and satellite services, and via wireless, the internet, or streaming. F&D reserved all other rights, including merchandising, novelization, print publishing, music publishing, soundtrack album, live performance, and video game rights to itself. Goldenrod and Voltage could execute agreements with third parties in their own names and they had “the sole and exclusive right of all benefits and privileges of [F&D] in the Territory, including the exclusive right to collect (in Sales Agent’s own name or in the name of [F&D] …), receive, and retain as Gross Receipts any and all royalties, benefits, and other proceeds derived from the ownership and/or the use, reuse, and exploitation of the Picture ….” The agreement described eight categories for deductions from the gross receipts, with the amounts redacted in the version given to the court. The pay out of any adjusted gross receipts after all the deductions were taken was also redacted.

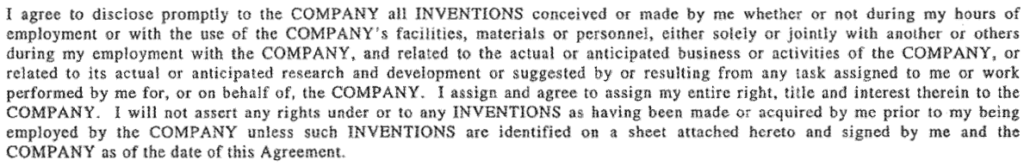

Goldenrod entered into a distribution agreement with Vertical Entertainment, LLC, granting Vertical a license in the US and its territories for the:

sole and exclusive right, license, and privilege … under copyright, … to exploit the Rights and the Picture, including, without limitation, to manufacture, reproduce, sell, rent, exhibit, broadcast, transmit, stream, download, license, sub-license, distribute, sub-distribute, advertise, market, promote, publicize and exploit the Rights and the Picture …

The “Rights” were:

(i) theatrical rights;

(ii) non-theatrical rights, meaning prisons, educational institutions, libraries, museums, army bases, hospitals, etc., but expressly excluding ships and airlines;

(iii) videogram rights, meaning videocassettes, DVDs, blue-ray discs, CD-ROMs, and similar media; retail channels including “through standard retail channels by means of download to any tangible or hard carrier Videogram storage device using any and all forms of digital or electronic transmission to the retailer,” and internet based retailers;

(iv) television rights;

(v) digital rights, meaning the exclusive right “in connection with any and all means of dissemination to members of the public via the internet, ‘World Wide Web’ or any other form of digital, wireless and/or Electronic Transmission &hellip including, without limitation, streaming, downloadable and/or other non-tangible delivery to fixed and mobile devices,” which includes “transmissions or downloads via IP protocol, computerized or computer-assisted media” and “all other technologies;”

(vi) pay-per-view and video-on-demand rights; and

(vii) incidental rights.

The license also included the right to assign, license or sublicense any of the enumerated rights.

As mentioned, Goldenrod retained the right of distribution to ships and airlines, plus clip rights, stock footage, merchandising, soundtrack, sequel, prequel, remakes, spin-offs, and royalties from retransmission and other collection agencies. The parties subsequently clarified that Vertical could distribute digital copies as long as Vertical uses commercially reasonable efforts to ensure that Vertical’s internet distribution and streaming could only be received within its contract territory, was made available over a closed network where the movie could be accessed by only authorized persons, and could only be accessed in a manner that prohibited circumvention of digital security or digital rights management security features.

The distribution agreement said that Goldenrod retained “the right to pursue copyright infringers in relation to works created or derived from the rights licensed pursuant to this Agreement,” which would include Zhang’s BitTorrent distribution.

Does F&D have standing to pursue the copyright infringement claim for Zhang’s alleged BitTorrent download?

The critical inquiry is to consider whether the substance of the rights or portions of rights that were licensed were exclusive or nonexclusive. Vertical plainly received exclusive rights. Vertical received the exclusive right to “manufacture, reproduce, sell, rent, exhibit, broadcast, transmit, stream, download, license, sub-license, distribute, sub-distribute, advertise, market, promote, publicize and exploit the Rights and the Picture and all elements thereof and excerpts therefrom” in the United States and its territories for almost all distribution outlets, except airlines and ships. This constitutes an exclusive license.

F&D argued that its retained rights were enough to give it standing, but the court didn’t agree:

F&D misunderstands Section 501(b) of the Copyright Act. [¶] As Section 501(b) states, and the Ninth Circuit has made clear, after a copyright owner has fully transferred an exclusive right, it is the transferee who has standing to sue for that particular exclusive right. The copyright owner need not transfer all of his or her exclusive rights, and will still have standing to sue as the legal owner of the rights that were not transferred. But the copyright owner no longer has standing to sue for the rights that have been transferred.

The BitTorrent download “squarely falls within the digital rights exclusively licensed to Vertical,” meaning that F&D couldn’t assert the claim. F&D’s ships and airplanes exclusion didn’t save the day, “The alleged violation also includes illegally viewing the movie in the United States, which is the exclusive broadcast territory of Vertical, except for airplanes and oceanliners, which are not relevant to this lawsuit.”

Goldenrod’s express retention of the right to sue for illegal downloads didn’t matter; the court noted that, since one could not assign a bare right to sue, “the Court finds that a party similarly cannot retain a simple right to sue. Just as Goldenrod (or F&D) could not assign or license to Vertical or anyone else no more than the right to sue for infringement, it cannot transfer the substantive Section 501(b) rights for display and distribution in the United States and its territories, including digital rights, but retain only the right to sue for one type of infringement of those transferred rights (illegal display and distribution over the internet).”

But wait, a beneficial owner also has standing to sue for infringement. “The classic example of a beneficial owner is ‘an author who has parted with legal title to the copyright in exchange for percentage royalties based on sales or license fees.” F&D had one problem with this argument though – lack of evidence:

The sales agency agreement provides that Goldenrod may enter into license agreements and collect monies in its own name. Thus, Goldenrod may collect the monies from Vertical in Goldenrod’s name. The sales agency agreement also provides, however, that monies obtained from licensing the movie shall be deemed “Gross Receipts.” As described in the factual background section, the first eight steps in distributing Gross Receipts could not be considered royalties to F&D.

It is conceivable that in the final step, after the monies become “adjusted gross receipts,” there may be some type of distribution that might be considered royalties to F&D. That entire section, however, is redacted in the copy provided to the Court. Thus, there is no way for the Court to know whether the adjusted gross receipts are divided in such a manner that could be considered royalties to F&D. F&D did not provide the Court with an unredacted copy or any evidence showing how F&D can be deemed to be receiving royalties. The Court would have to engage in pure speculation as to how adjusted gross receipts are divided, and the Court will not do so.

Case dismissed.

Fathers & Daughters Nev., LLC v. Zhang, Civ. No. 3:16-cv-1443-SI (D. Or. Jan. 17, 2018)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

- Not mentioned by the court, Voltage Pictures has a notorious reputation for “copyright trolling,” which is using the court system to obtain the identity of a file downloader without any intention of suing them and then demanding money. ↩