There’s something that doesn’t seem right about this case, but then it’s a band case. Those are in their own trademark world.

This one is about The Rascals. The original members of The Rascals (originally known as The Young Rascals), formed in 1965, were Felix Cavaliere, Gene Cornish, Eddie Brigati and Dino Danelli:

(Dig the outfits. This was at the time of the British Invasion, so even though they were Americans I guess looking British was the way to go.)

Brigati left the Rascals in 1970 and Cornish left in 1971. Wikipedia says that the band broke up in 1972.

Fast forward to 1988 when Cavaliere produced a reunion tour, in which Cavaliere, Cornish, and Danelli participated, but Brigati did not. Danelli and Cornish then wanted to continue performing without Cavaliere but Cavaliere objected, with the three ending up in a lawsuit. The lawsuit ended with Danelli and Cornish performing under the name “The New Rascals, featuring Dino Danelli and Gene Cornish” and Cavaliere could perform as “Felix Cavaliere’s Rascals.” Brigati was not a party to this agreement.

In 1990 Brigati entered the picture again, filing a lawsuit over the rights to recordings and other band assets. The case settled in 1992 with a written agreement signed by all four members. The agreement covered the allocation of proceeds from the sale of Rascals recordings and included procedures for future decision-making about the disposition of Rascal assets, but did it not address live performances. To implement the agreement, the four band members formed a “pass through” partnership in New Jersey that distributed revenues and “owns the rights to the RASCALS and YOUNG RASCALS marks for musical sound recordings.” Registrations aren’t mentioned in the opinion, but there are registrations for RASCALS and YOUNG RASCALS for “musical sound recordings” owned by a New Jersey partnership called “The Young Rascals” and listing the four band members as the partners.

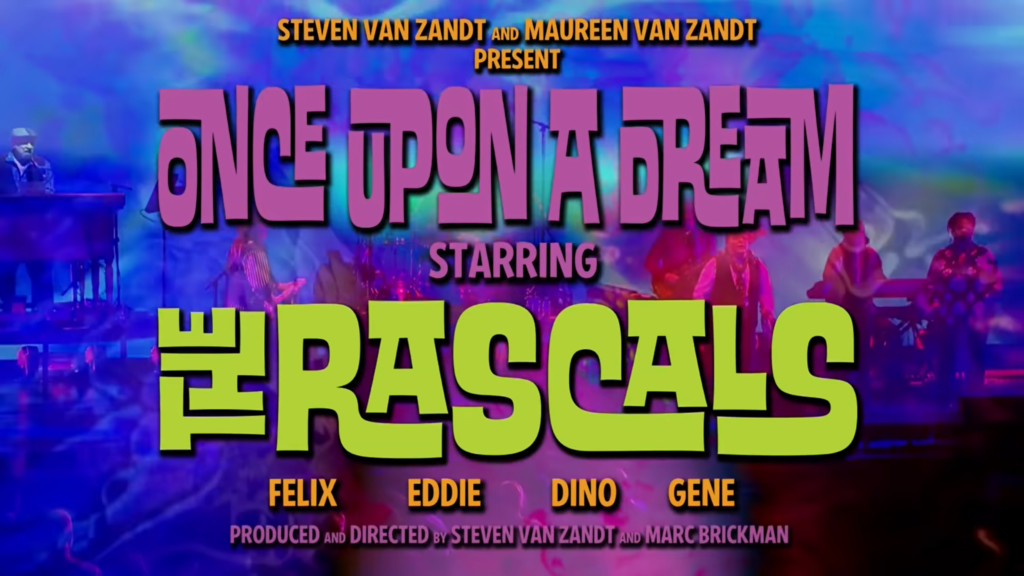

Cavaliere toured in the 1990s and 2000s. In 2012 and 2013, the four performed together in a musical,

but it was cancelled because it was unprofitable.

In 2017 Cavaliere proposed a final tour with all four original band members. Cornish agreed, Brigati declined, and Danelli initally agreed but ultimately backed out. Cavaliere and Cornish formed plaintiff Beata Music, LLC and the two transferred to it “any rights they had in the RASCALS mark for live performances.” Beata Music filed a trademark application for the mark, which has been opposed by Brigati and Danelli.1 After negotiations with Brigati and Danelli, the tour was named “Felix Cavaliere and Gene Cornish’s Rascals.”

Beata Music filed a declaratory judgment against Brigatti and Danelli asking for a declaration of non-infringement and a declaration that Brigati and Danelli did not have any rights to the trademark THE RASCALS for live performances and related merchandise. Danelli dropped out of the suit, so the decision is only about Brigati’s rights.

The parties agreed that the Young Rascals partnership owns the trademarks for sound recordings but the movants argued, as described by the court, “that Brigati has abandoned his interest in the RASCALS mark” – presumably meaning the mark as used for live performance. After reciting the standard for abandonment, the court reached the unsurprising conclusing that Brigati, who had not performed as part of The Rascals since 1970 except for the short-lived musical, had abandoned the RASCALS trademark.

Let’s put aside the concept that it’s possible for the trademark for sound recordings and performance to be owned by separate entities. It seems counterintuitive but I suppose: the records are for a band that existed in the past but no longer exists and the live performance is for a “new” band, although it’s playing the original music (or else the band would have chosen a different name). So I’m not buying it, but the USPTO apparently does—the currently existing and presumably valid registrations owned by the New Rascals partnership for sound recordings were not cited as likely to be confused with the Beata application for live performances and the Beata application was published. I think that’s pretty questionable, but, as a I mentioned, trademarks for band names are different.

But is Brigati’s own non-use the right way to think about it? Doesn’t the court’s analysis suggest that each of the four original members have independent rights in the trademark THE RASCALS, that they each can abandon, one by one? That seems to be the only way to reach a conclusion that Brigati’s cessation of use was a trademark abandonment, but only as to Brigati. That’s not how trademark abandonment works, though. The mark THE RASCALS was for a collective, one that was even formalized as a partnership for purposes of the trademark rights for the musical recordings. For an abandonment the entity has to cease use, not just one individual member.

Maybe a better way to think about it is that THE RASCALS mark for live performances has been abandoned altogether. Splinter bands generally use qualfiers to distinguish themselves from the original, often as the result of a lawsuit. One could argue that consumers aren’t confused that they’re seeing a splinter band because of the naming convention, understanding that it is not all (or maybe any) of the original members. A decision that THE RASCALS was abandoned for live performances because no one had performed as THE RASCALS for years would have made sense, and reached the same outcome. But saying that Brigati alone abandoned his rights was an expediency, not a legally justifiable decision.

Beata Music LLC v. Danelli, No. 18-cv-6354(JGK) (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 6, 2022)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

- Oddly, although the opposition is filed in the names of Brigati and Danelli, the New Rascals Partnership trademark registrations were listed as a basis for the opposition. The Notice of Opposition somehow skips past the fact that Brigati and Danelli don’t actually own those trademark registrations, saying only that Brigati filed the application on behalf of the partnership (he did, in fact, sign it). ↩

Leave a Reply