I suggested in a recent blog post that the Copyright Act should be amended to eliminate the requirement that a copyright must be registered before one can file a copyright infringement lawsuit. My position is that the registration does nothing to aid the court in its decisionmaking and the additional step it adds to the lawsuit, the attack on the registration, makes copyright litigation more expensive and time-consuming.

I suppose the theory is that the registration reduces some burden on the courts. By statute, a certificate is prima facie evidence that the copyright is valid, i.e., the work is copyrightable, and that the facts stated in the certificate are accurate. 17 U.S.C. § 410. This is only true though if the registration was made within five years of publication; if the registration was after that, or the work was unpublished, then the evidentiary weight is within the discretion of the court. So already we can see that the registration is of questionable value.

But the irrelevance of the certificate goes further than that. The owner listed on the certificate may not be the owner now; the copyright may have been assigned, requiring an examination of chain of title. Or the claim may involve a license, so standing is an issue. Often a copyright infringement claim involves questions of joint authorship (every lawsuit over a commissioned work has a joint authorship allegation lurking). A certificate claiming a work was made for hire won’t be the end of it; the parties will litigate whether the facts actually support the claim. The authorship and ownership stated on a certificate is only a jumping off point, but is by no means dispositive.

Nor is an examination of a copyright application a deep dive into the originality of the work. It is binary, “yes,” copyrightable, or “no,” not copyrightable. But the scope of copyright, which matters for infringement, is far more complicated than that. Is the copyright “thin” because it is a factual work, a depiction of something existing, like a jellyfish, or are some elements so commonplace that they are scenes a faire? If it is a compilation or derivative work, what are the earlier works and how much was used? The fact of registration is little or no help to the court in sorting these questions out.

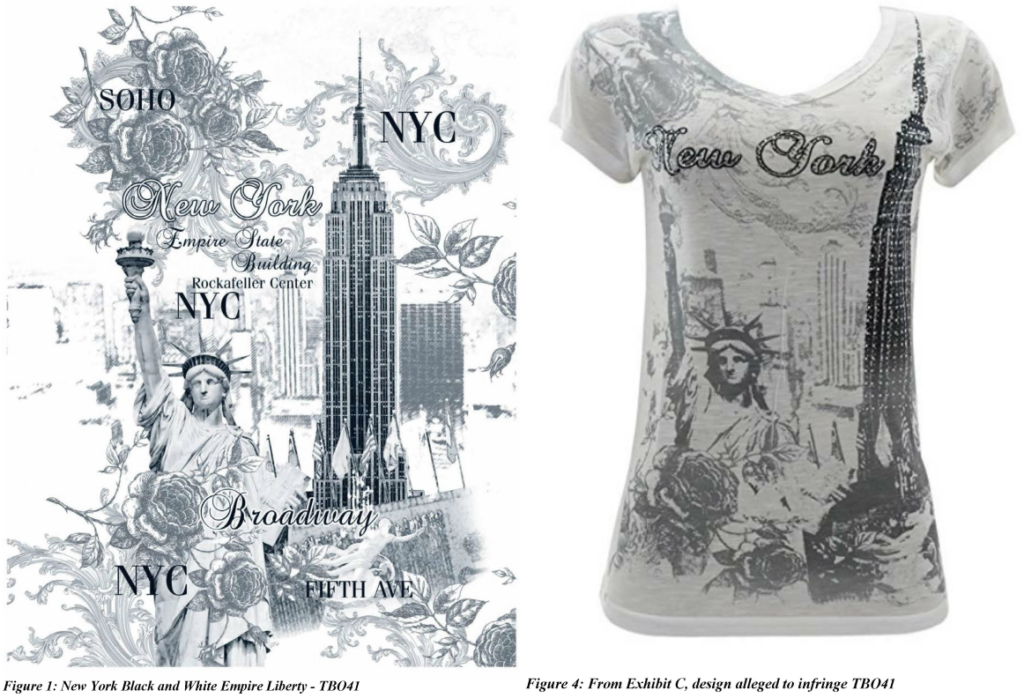

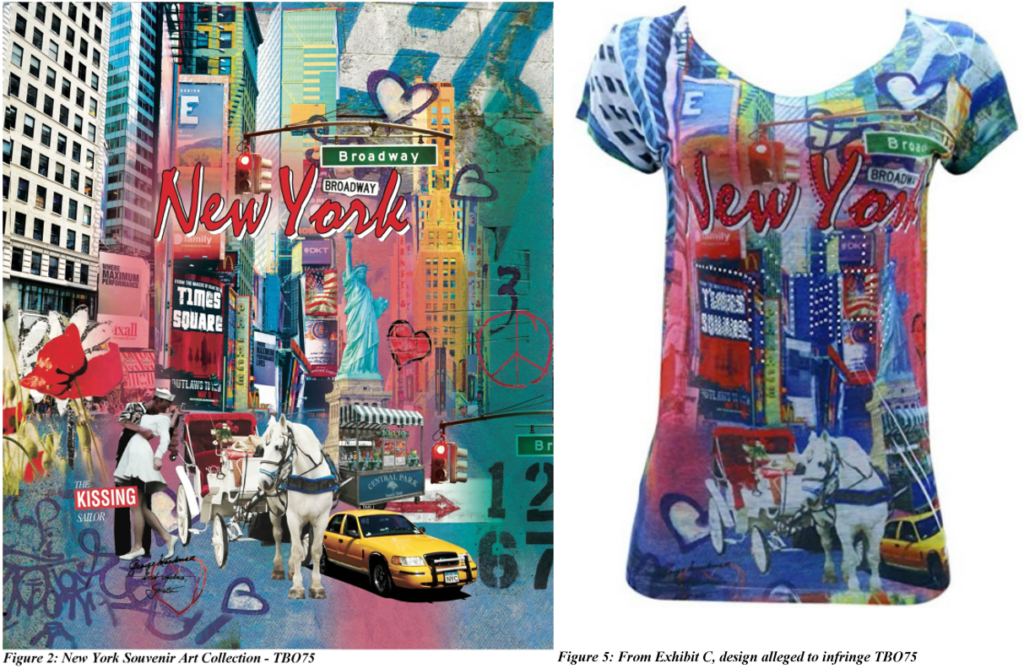

And courts do just fine at figuring it all out, no matter what the certificate says. Today’s example is Sweet Gisele, Inc. v. True Rock CEO, LLC, a case about copying souvenir T-shirt designs. Below are the works at issue, the registered work on the left and the accused work on the right (click to embiggen):

The defendant defaulted; even so the magistrate denied the motion for default judgment. So while there was no adversary to point out the weaknesses of the plaintiff’s claims, the court nevertheless had no problem examining the facts and found them wanting.

A copyright claim requires proving ownership of a valid copyright, what the registration process theoretically examines, and copying of constituent elements of the work that are original. The ownership element requires that the plaintiff sufficiently prove both that it owns the copyrights in question and that the copyrights are valid.

On proof of ownership, in this case the registration provided some evidence that aided the court. The complainant was Sweet Gisele and the complaint said Sweet Giselle was the owner and author of the works. However, the registration certificate listed Josef and Lidor Cohen as the authors of works made for hire. The court pointed out the discrepancy and asked the plaintiff for more information. Thereafter, Sweet Gisele told the court that the works were created by one Shalom Mallachi and the Cohens acquired the copyright through transfer. But a declaration signed by the Cohens did not mention any assignment, and the assignment dates in the assignment agreements were before the year of completion of the works stated on the certificates. The court also questioned in a footnote whether one registration certificate was even for the works in question, but let that slide. There also appeared to be no documentary evidence of a written assignment from the Cohens to the plaintiff; the entity’s claim of ownership was testimonial only. The court therefore held that the plaintiff had not proven its ownership of the copyrights.

So the registration certificate had some value to the court; it exposed inconsistencies in the claim of ownership. However, without a registration certificate, the plaintiff still has the burden of proof on ownership. The proof would necessarily include evidence of the full chain of title from the author of the work to the plaintiff, something that appears not to exist here. The inconsistency between the complaint and the registration may have been the first sign that something was amiss, but the problem is not something that otherwise would not have been discovered.

Although the copyrights were registered, and therefore entitled to a presumption that they were valid, this case shows why often that just isn’t enough. Here, the court still had to assure itself that the works were original and creative. Even after supplemental briefing from the plaintiff, it wasn’t so sure:

Plaintiff, in its supplemental submissions, extensively cites irrelevant case law regarding protection of photographs. These images are clearly not, however, original photographs. By plaintiff’s own admission, these designs are “graphic and computer-enhanced interpretations of famous New York building[s] and themes.” These works clearly draw heavily on preexisting material—common images of famous New York City landmarks. They thus appear to be either compilations or derivative works. From the pleadings, however, it is unclear whether that material it draws on is itself in the public domain or is otherwise subject to copyright protection.

Compilations and derivative works are eligible for copyright protection, 17 U.S.C. § 103(a), but they must still constitute original works of authorship. Moreover, such protection extends only “to the material contributed by the author of such work, as distinguished from the preexisting material employed in the work, and does not imply any exclusive right in the preexisting material.” 17 U.S.C. § 103(b). In addition, that protection “does not extend to any part of the work in which such material has been used unlawfully.” 17 U.S.C. § 103(a).

The court explained at length why it wasn’t so sure that the works were entitled to copyright protection. It describe the photographic images as mere depictions of reality. It stated that dramatic representations of Lady Liberty’s torch are “pervasive” in American visual culture (with illustrations) so the use here therefore a scene a faire. It also described putting Lady Liberty in front of New York’s two most iconic buildings, the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building, “standard, unoriginal, and therefore unprotectable.”

The plaintiff argued essentially that the collaging of the various constituent images created an original whole, but even that didn’t persuade the court:

To be sure, courts have found specific layouts or graphic designs that contain otherwise public domain images to be copyrightable. In such cases, however, plaintiffs have established that those layouts or designs were, in fact, original. Thus, courts in this circuit have rejected the notion that taking a public domain image and placing it on a generic background is a sufficiently original design to create a valid copyright. Similarly, the Second Circuit has affirmed that there is no copyright protection for a background component of a design when another design is placed on top of that background, and the background is copied from a public domain source.1

The court’s view was that the plaintiff therefore had not met its burden of proving originality, even though it had registered copyrights.

Moreover, the court mentioned that plaintiff said it purchased artwork from a graphic designer, but did not delve into what that might also mean for the copyrightability of the shirt designs.2 It might be that those underlying works weren’t properly licensed, meaning the derivative work was unlawful. It also would only be in comparing the original to the derivative work that one could discern what might be original in the new work. This is yet another area where the fact of registration has nothing to offer the court in the way of help; when examining copyright the Copyright Office does not explore whether the underlying work was properly licensed or not, or compare source works and the derivative work. This is entirely within the court’s purview.

The point here is not whether the court was right or wrong on copyrightability, but rather this case highlights that the existence of a copyright registration, and a presumption that something is copyrightable, is of very little use to a court. The court still has to tease out exactly wherein the originality lies.

To complete the cycle, assuming arguendo that there was a copyright, the court also held that the plaintiff had not proven that its “thin” copyrights in the designs were infringed:

I am not persuaded, however, that the images are close enough to constitute extremely close copying of the protectable elements of plaintiff’s designs, under the “more discerning” test endorsed by the Second Circuit in such cases. There are, for one, visible differences: for example, the alleged infringing copy of TBO41 appears to blur or omit much of the background rose pattern and incorporates rhinestone decoration. Similarly, the alleged infringing copy of TBO75 appears not to incorporate the “Kissing Sailor” photograph, and incorporates additional rhinestone decoration. Finally, TBO86 appears to have quite different, arguably more vivid, coloring, and to be embroidered with rhinestones in place of the rays of the torchlight.

I am unable to say copying has occurred here because plaintiff has not met its burden of establishing that its designs include protectable elements. I therefore cannot reasonably conclude that there has been copying of such elements, as opposed to the permissible taking and re-creation of the public domain imagery and ideas expressed in plaintiff’s designs.

I have no objection to permissive registration and the benefits given to those having a registration, such as statutory damages. I have no problem with a certificate being prima facie evidence of the facts stated on it (which this case shows can cut both ways). But the registration requirement is of little to no value to a court yet puts a significant barrier in the way of the plaintiff, both by delaying a lawsuit by having to file an application (and in some circuits, wait for it to register) and then by spending an extra year of litigation on a collateral attack on the statements on the registration before even getting to the substance of the claim. It is nothing but a trap.

Sweet Gisele, Inc. v. True Rock CEO, LLC, No. 17 CV 170 (FB)(RML) (E.D.N.Y. Sep. 4, 2018); adopting Report and Recommendation No. 17 CV 170 (FB)(RML) (E.D.N.Y. Sep. 28, 2018)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

- The court even went so far as to identify an image from a video game that was very similar to a portion of one of the shirts. Compare the words “From the makers of” on the red sign in both images. ↩

- Note in this case too that the plaintiff had not mentioned in its registration certificate, as it was required to do, that there were preexisting works used in the designs. Nevertheless, the court had no problem figuring that out and considered the information when deciding copyrightability. ↩

Leave a Reply