Plaintiff Janssen Biotech had a fundamental structural problem with an agreement. The document was called an “Employee Secrecy Agreement,” but in addition to imposing duties of confidentiality on its employees the agreement also served as an employee invention assignment agreement, as is commonly, if not universally, done.

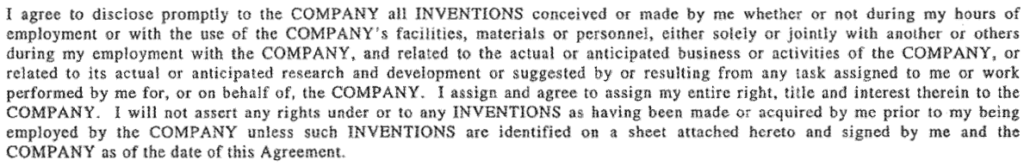

Janssen’s structural problem was in the definition of the parties to the agreement. Here is the definition:

![]()

If you can’t read it, the agreement defines COMPANY as “CENTOCOR and JOHNSON & JOHNSON and any of their … subsidiaries, divisions and affiliates ….” Plaintiff Janssen Biotech was a successor to Centocor.

This is a very expansive definition, good if you are obliging your employees to confidentiality. But for the patent assignment, it wasn’t such a great definition:

In the patent assignment provision, the employee is “assign[ing] and agree[ing] to assign my entire right, title and interest … to the COMPANY” all the employee’s inventions.

Defendant Celltrion claimed that the employee-inventors of the patent-in-suit had assigned their patent rights to “more than 200 other companies, including Johnson and Johnson (“J & J”) and its subsidiaries and affiliates.” Of course, if that was the correct interpretation of the assignment, then J & J and all the subsidiaries and affiliates would have to be joined as plaintiffs. However, the court reached the view advocated by Janssen, that the patent rights were assigned only to the inventors’ employer, Centocor.

New Jersey law applied to the construction of the agreement. Under New Jersey law,

A contract is not clear and is instead ambiguous if its terms are susceptible to at least two reasonable alternative interpretations, or when it contains conflicting terms. If the contract is ambiguous, the court must give the contracting parties practical construction of the contract controlling weight in determining a contract’s interpretation.

To determine whether a contract is ambiguous, and to discover the intention of the parties, courts may consider evidence outside the text of the contract. Such extrinsic evidence includes the circumstances leading up to the formation of the contract, custom, usage, and the interpretation placed on the disputed provision by the parties’ conduct.

To decide whether a contract is ambiguous, we do not simply determine whether, from our point of view, the language is clear. Rather, we hear the proffer of the parties and determine if there are objective indicia that, from the linguistic reference point of the parties, the terms of the contract are susceptible of different meanings. Before making a finding concerning the existence or absence of ambiguity, we consider the contract language, the meanings suggested by counsel, and the extrinsic evidence offered in support of each interpretation. Extrinsic evidence may include the structure of the contract, the bargaining history, and the conduct the parties that reflects their understanding of the contract’s meaning.

(Internal quotations, citations, ellipses and brackets omitted.)

The court had no problem reaching the conclusion that the term COMPANY was ambiguous. With respect to “any subsidiaries,” “any” sometimes means “all” or “every,” for example, “any attempt the flout the law will be punished.” Or it might mean one or more unspecified things or people, to be specified later. Here, it probably meant the latter. But that didn’t fully solve the problem – the assignment was to “Centocor and Johnson & Johnson.”

But construing COMPANY to mean both Jenssen and J & J conflicted with other parts of the agreement. The next sentence out the outset of the agreement was “Affiliates of the COMPANY are any corporation, entity or organization at least 50% owned by the COMPANY, by Johnson & Johnson or by any subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson.” The use of COMPANY here suggested J & J wasn’t to be considered “COMPANY.” Also, the assignment of the inventions was “during [his] employment with the COMPANY.” The inventors weren’t employed by both companies, only Centocor, suggesting again in this context that COMPANY meant only Centocor.

The court therefore found the agreement ambiguous and moved on to extrinsic evidence. Janssen, J & J, and the other J & J companies understood that the rights were assigned only to the employing company. J & J’s patent database listed only the employer as the patent owner. The agreement required that employees disclose new inventions to COMPANY and these inventors disclosed their inventions to Centocor only. The subject agreement here had later been revised to make it clear the patent assignment was to the employing company. No other J & J subsidiary ever claimed to have rights in the patent-in-suit.

On the other hand, in at least eleven other cases J & J and/or other companies in the J & J family relied on the more expansive view of COMPANY. These were cases where a non-employing J & J family member joined the employing company in enforcing the confidentiality provisions of the agreement.

Generally a term will have consistent meaning throughout a document. However,

the presumption of consistent usage readily yields to context, and a statutory [or contractual] term—even one defined in the statute [or contract]—may take on distinct characters from association with distinct statutory [or contractual] objects calling for different implementation strategies.

This rule of interpretation therefore wasn’t enough to persuade the court when balanced against the words of the agreement and the extrinsic evidence. Further, none of the eleven cases were brought by Janssen, so Janssen had not taken an inconsistent position. So the court concluded that Centocor was the only assignee and the court therefore had jurisdiction over the patent infringement suit.

There was, though, one failing argument. After the suit was filed, Jenssen and J & J entered into an agreement stating that Janssen was the sole owner of the patent and that neither J & J nor any of its operating companies owned any interest in the patent. But it doesn’t work that way:

The Federal Circuit has never held that co-owners of a patent are not required to be joined as plaintiffs if they disclaim their interest in the patent. Janssen relies primarily on IpVenture, Inc. v. Prostar Computer, Inc., 503 F.3d 1324 (Fed. Cir. 2007). IP Venture involved the question of whether a contract was an assignment of a patent or an agreement to assign it. The Federal Circuit held that the contract was an agreement to assign. The court further found that this interpretation was “reinforced” by a statement made by the purported assignee that it never had any legal or equitable rights to the patent at issue. Therefore, the court in IP Venture essentially considered the disclaimer as extrinsic evidence supporting its interpretation of the agreement at issue. IP Venture does not provide an alternative basis for finding that Janssen has standing to bring this cases because the Agreements assigned the ‘083 Patent to its predecessor Centocor alone.

I’m not sure that every court would reach the conclusion that Janssen was the sole owner of the patent – maybe about the “any” part, but not necessarily that Centocor and J & J weren’t joint owners of the patent. New Jersey seems to me to have a very generous view on the use of extrinsic evidence, and that saved Janssen’s bacon here. Needless to say, it’s better to have clean agreements to start. I often say that the mischief will be in the definitions.

Janssen Biotech, Inc. v. Celltrion Healthcare Co., No. 17-11008-MLW (D. Mass. Oct. 31, 2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Leave a Reply