I’m SO glad you did, because I can tell you all about the Trolley Pub® transport services – note the care with which I’ve used the term as a trademark, although I will dispense with any effort to use it in adjective-noun form from now on.

The Trolley Pub is a pedal-powered street trolley for hire. “Pub” because you can bring alcoholic beverages on the trolley. It has a driver, presumably not drinking, who steers, brakes and encourages more pedaling when necessary for propulsion (sometimes they’re too occupied with drinking and forget). The Trolley Pub takes you wherever through town you would like to go. I suppose the Trolley Pub could drive you from museum to museum if that was your desire, but I’m guessing that it is generally used to go from bar to bar.1

How do I know so much about the Trolley Pub? Because the Trolley Pub’s departure point is about two blocks from where I live. I’m on an intersection of two busy streets, so I see the Trolley Pub many times a day in the warmer weather. One of the streets is a one-way downhill grade, which apparently means it is obligatory to yell “wheeeeeeee!” as you go down it (I suppose because of the intoxicated joy in being relieved of your pedaling duties). My favorite passengers were some fans of show tunes, singing Phantom of the Opera lustily (when not “wheeeeeeee”-ing) and doing a very enthusiastic Bohemian Rhapsody, which, while not technically a show tune, in my opinion is as good as any show tune for an amateur sing-a-long. Maybe better.

And so with that for background we reach the case, about a failed claim for partial ownership of the Trolley Pub business and intellectual property. Honestly it’s not all that interesting and you can stop reading now, I’m just writing about the case because it’s about the micro-regionally famous Trolley Pub (everyone in Raleigh knows Trolley Pub, and probably has been stuck behind its slow progress in traffic, except on downhills). So we’re getting to the boring part now.

Trolley Pub started, according to the trademark registration, in 2011. Andrew Cole and Kai Kappro own Kaapro & Cole Ventures, which presumably was the original owner of the Trolley Pub business. On February 29, 2012 Kaapro & Cole Ventures joined with Jeff Munson to form Trolley Pub of North Carolina, LLC (TPNC). Munson contributed $40,000 in return for 27.78% ownership and Kaapro & Cole Ventures contributed the Trolley Pub logo, the Trolley Pub trademark, the Trolley Pub image and branding, know-how, marketing plans, technical information, supplier lists and information, financial plans, contractor and builder information, business plans, management commitment, software, and design work for the remaining 72.22% ownership.

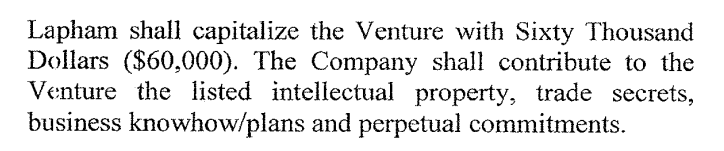

In late 2012 and early 2013 plaintiff Thomas Lapham, Kaapro and Cole discussed expanding the business to Virginia, Maryland, DC and Delaware. Lapham claims that the conversations were that he would get 50% ownership interest in that region, which he would operate, and TPNC would contribute the trademarks and other intangible property. On February 4, 2013 they executed a Memorandum of Terms for a Proposed Business Partnership Agreement. The agreement described the contributions:

If you can’t read it, Lapham was to contribute $60,000 for half of the business and TPNC was to contribute the intellectual property. But, the agreement continued:

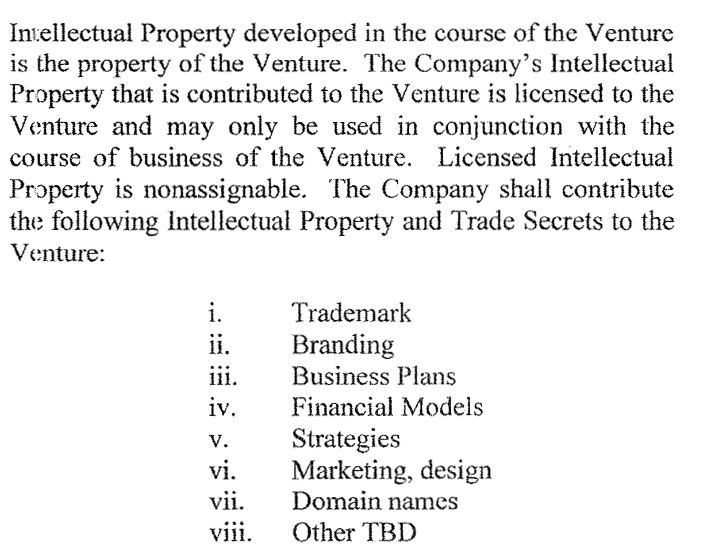

If you can’t read this, it says

Intellectual Property developed in the course of the Venture is the property of the Venture. The Company’s [TPNC’s] Intellectual Property that is contributed to the Venture is licensed to the Venture and may only be used in conjunction with the course of business of the Venture. Licensed Intellectual Property is nonassignable. The Company shall contribute the following Intellectual Property and Trade Secrets to the Venture:

going on to list a number of intangibles, including the trademarks. So while saying that there would be a “contribution” of intellectual property was an unfortunately worded general description, it was clear that the contribution was a license to the rights, not ownership.

The parties never agreed on an operating agreement for Trolley Pub of Virginia,2 for reasons not explained. Lapham nevertheless claims to have invested $400,000 in the business. In May or June, 2014 there were also discussions for a holding company, including a draft agreement, where Lapham would contribution $400,000 and Kaapro & Cole Ventures would contribute the intellectual property, but that also never came to fruition. On December 2, 2015, Kaapro & Cole Ventures and TPNC executed an Intellectual Property Assignment and License Back Agreement, where TPNC assigned the intangibles back to Kaapro & Cole Ventures in exchange for a license-back for exclusive use in North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia and non-exclusive rights elsewhere. A few days later they told Lapham that they were not going to contribute the intellectual property.

Lapham sued TPNC, Kaapro & Cole Ventures, Kaapro, and Cole for fraud, fraud in the inducement, breach of contract, and anticipatory breach of contract. This decision is about Lapham’s second try at stating a claim – he didn’t.

I will interject a personal view at this point – to me, $60,000 to run a Trolley Pub franchise in four states sounds right, but Lapham’s theory that he would own half of the rights in Trolley Pub intangibles nationwide for $60,000 was laughable. Trolley Pub in Raleigh was at that point in time an exceptionally successful and fast-growing business. On my recollection, it had grown from one vehicle when it started to probably three by the time of the supposed assignment. The intangibles were also valued at about $160,000 a year earlier, when they were contributed by Kaapro & Cole Ventures to TPNC. This theory doesn’t pass the smell test. $400,000 though, maybe now we’re talking.

On the fraud and constructive fraud claims, fraud must be pleaded with particularity but wasn’t:

All of Lapham’s fraud claims fail at the first element because the Complaint does not allege any facts that constitute a false representation. Throughout his pleading, Lapham asserts:

At the time that the … promises were made, Kaapro and Cole had no intention to perform those promises …. Instead, Kaapro and Cole intended to maintain ownership and control of the Trolley Pub Intangible Property and grant rights in such property to a competing entity or entities in which Lapham had no ownership interest but that would be authorized to operate the Trolley Pub Business in those states….

Lapham repeats some form of this language for each of the alleged promises Kaapro and/or Cole made to him in February 2013, March 2013, and June 2016. Thus, the Complaint argues that Defendants’ professed intent to perform the promises was never genuine, and was therefore false. Without any facts to support this legal conclusion, however, the claims must fail.

In support of his argument, Lapham conflates the “intent to mislead” and “false representation” elements of fraud. Essentially, he argues that Defendants “intended to mislead” him, and therefore they made a “false representation.” This argument overlooks the fact that the elements of fraud are separate and distinct …. Aside from Lapham’s conclusory allegations, there is nothing in the Complaint to suggest that Defendants did not intend to follow through on their promises. There is no allegation of side dealings with other companies, conspiracies, embezzlement, misstatements of bank records, misrepresentations of profitability, improper auditing procedures, or any of the other telltale signs of fraud. To the contrary, the Complaint suggests that all parties intended for this business relationship to endure.…

Accepting Lapham’s theory of fraud would transform every breach of contract case into a fraud case. Plaintiff essentially alleges that “Defendants had no intention of fulfilling their side of the bargain when they entered into it, and therefore they misstated a material fact.” Without support for these alleged misrepresentations of intent, this is an assertion that every businessman could claim if his deal went awry. For example, if a merchant failed to deliver goods as required by contract, the buyer could claim that the seller did not deliver the merchandise, “and never had an intention to do so.” This result would undercut the reasoning behind 9(b), which seeks to protect defendants from harm to their reputations as well as from frivolous lawsuits. … As such, if Defendants did not fulfill their promises in a bargained-for exchange, the law of contracts, rather than the tort of fraud, will provide Plaintiff his relief.

But the law of contracts provided no relief either. The only signed agreement was the Memorandum, which was quite clear on what intangibles TPNC would contribute, a license. Lapham did not successfully allege any oral contract because he could not state any critical terms with particularity. There had also been written drafts subsequent to oral conversations, suggesting the conversations were negotiation, not agreement:

With regard to the oral contract from early 2013, it appears those discussions were memorialized and given effect on February 4, 2013, when the parties executed the Partnership Agreement. With regard to the “amendment” on or around March 4, it appears that those negotiations were embodied in the TPV agreement, which Lapham never executed and is therefore not legally binding. The fact that actual contract documentation was produced following the parties’ negotiations suggests that the discussions that Lapham references were in fact preliminary negotiations, and not separate oral contracts, as alleged. Lapham cannot reject each of the draft agreements that were offered to him in definite terms, and then turn around and enforce the ambiguous negotiations of those documents as though they were valid contracts. Without contractual obligations on either side, there could be no breach, and therefore Lapham’s claims must fail.

The case was dismissed with prejudice. Wheeeeeeee!!

Lapham v. Trolley Pub of NC, No. 1:16-cv-469 (E.D. Va. Dec. 12, 2016).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

- One might ask why an open container on a vehicle in the middle of the street is permitted but an open container on the sidewalk is not. One of those mysteries of life, I guess. ↩

- Lucky for them. The agreement, already executed by TPNC, didn’t have the clarification that only a license was being contributed. ↩

Leave a Reply