Golly, the things you have to explain sometimes. Plaintiff Ubu/Elements, Inc. claimed to have purchased all of the assets of Defendant Elements Personal Care, Inc. UBU/Elements accused the defendant of continuing to use the trademark AFTER THE GAME after the purchase.

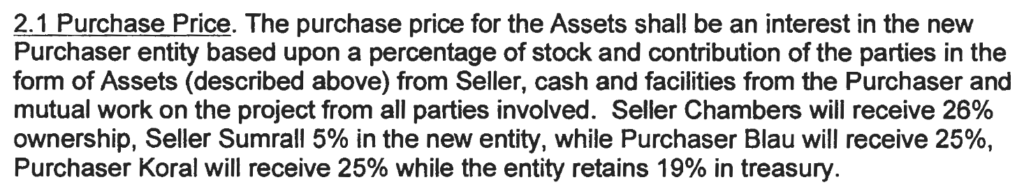

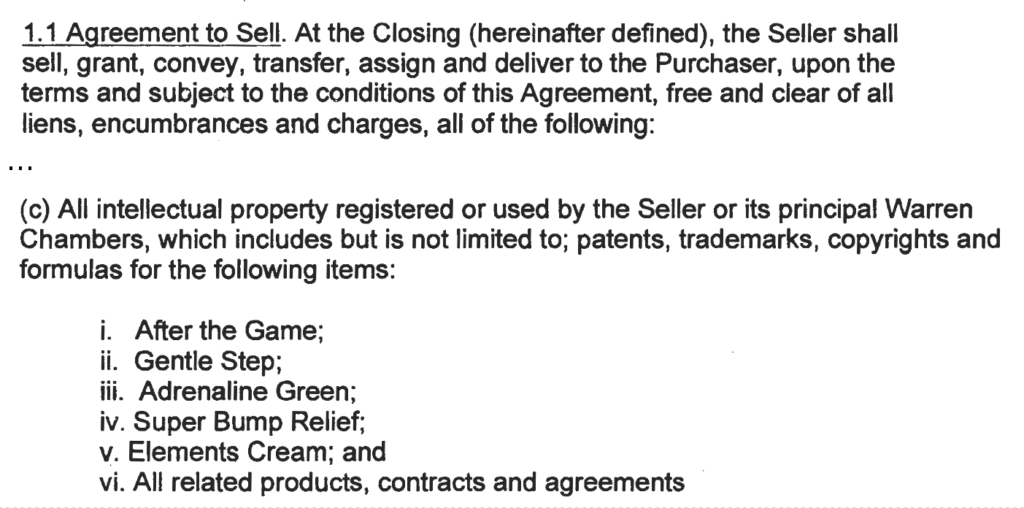

The Asset Purchase Agreement said this about the trademark in dispute:

If you can’t read it, it says that at “Closing” Elements Personal Care would “sell, grant, convey, transfer, assign and deliver to the Purchaser … all of the following: … All intellectual property registered or used by the Seller or its principal Warren Chambers, which includes but is not limited to: patents, trademarks, copyrights and formulas for the following items: i) After the Game.” Consideration for the purchase of the assets was that Warren Chambers would become a 26% shareholder in a new entity known as UBU/Elements, Inc., and the other shareholder in Elements Personal Care, Inc., Arthur Sumrall, would become a 5% owner:

There was no separate trademark assignment agreement. The APA was recorded at the PTO after the dispute began.

So here’s the problem—the APA used language of future assignment, “at the Closing the Seller shall sell ….” There was no closing on the date given for it in the APA, November 8, 2011. But the paragraph continued on “or on such other date and at such other time or place as the parties may agree in writing.” It is apparently undisputed that on November 23, 2011, both the APA and the Shareholder Agreement for the new company were signed, so there was a closing. And the documents they had, although not ideal, were good enough for the court:

The record is clear that the APA was signed by all of the interested parties, and the Shareholder Agreement was simultaneously signed on that same date. I am persuaded by a preponderance of the evidence that this exchange of promises, and the simultaneous execution of both documents, was sufficient to establish a binding written contract, and that such contract operated to assign the ATG trademark to Plaintiff.

I conclude that that this is the plain meaning of the documents, and this construction of the two agreements is consistent with and corroborated by other evidence, including the conduct of the parties. Although it would have been preferable and certainly would have added clarity if there were a separate document specifically purporting to transfer the trademark, the agreement itself leaves the form of documentation required to effectuate transfer strictly within the control of the purchaser. Specifically, Section 3.2 entitled “Transfer of Assets” provides that the “Seller shall deliver to the Purchaser … assignments and other good and sufficient instruments of conveyance and transfer, in form and substance reasonably satisfactory to the Purchaser’s counsel.” Alan Blau testified that he, as an officer of UBU/Elements, was satisfied at the time of the closing that the documents executed adequately reflected the assignment of ATG.

The defendant didn’t really have a leg to stand on here; in fact I believe the argument borders on the frivolous. The defendant didn’t claim that the entire purchase didn’t happen (which is the logical outcome of it’s “closing” theory), just that one trademark out of a list of identically situated ones wasn’t transferred. This is what makes litigation so painful sometimes. The defendant was able to do a lot of hand-waving to apparently convince the court that it should be looking for some document called a “trademark assignment,” absolutely not true, forcing the plaintiff to draw a connect-the-dots for the court. The court cannot be expected to know the intricacies of trademark practice but the parties should, and not make arguments based on unsupportable theories.

The plaintiff wasn’t without fault either though; it tried to claim that (1) recording the APA was proof of the assignment, clearly contrary to Section 3.54 of the Code of Federal Regulations and Section 503.01(c) of the Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure, which state that the recording is merely ministerial; and (2) the assignment of a registered trademark does not have to be in writing, clearly contrary to what Section 10 of the Lanham Act says.

Ubu/Elements, Inc. v. Elements Personal Care, Inc., No. 16-2559 (E.D. Pa. Aug 19, 2016).

Ubu/Elements, Inc. v. Elements Personal Care, Inc., No. 16-2559 (E.D. Pa. June 22, 2016) (denying TRO).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Leave a Reply