I previously posted about a copyright infringement suit with three registrations for the same work, brought by William L. Roberts aka Rick Ross, and Andrew Harr and Jermaine Jackson aka The Runners, alleging infringement of a musical work titled “Hustlin’.” I asked what happens on a motion for summary judgment on the questions “was the musical composition Hustlin’ validly registered by the Copyright Office, and, if so, do Plaintiffs have an ownership interest in the exclusive right to prepare derivative works for the musical composition Hustlin’?”

I previously posted about a copyright infringement suit with three registrations for the same work, brought by William L. Roberts aka Rick Ross, and Andrew Harr and Jermaine Jackson aka The Runners, alleging infringement of a musical work titled “Hustlin’.” I asked what happens on a motion for summary judgment on the questions “was the musical composition Hustlin’ validly registered by the Copyright Office, and, if so, do Plaintiffs have an ownership interest in the exclusive right to prepare derivative works for the musical composition Hustlin’?”

On the first question, the court held that the work was not validly registered. As required by Section 411(b)(2) of the Copyright Act, the court obtained the opinion of the Register of Copyrights. The Register opined that, had it been aware of the facts as stated by the court, none of the three registrations would have been registered.

On the first, the registration listed the work as unpublished but, in fact, it had been published before the application date. The Copyright Act defines “publication” to include “[t]he offering to distribute copies or phonorecords to a group of persons for purposes of further distribution, public performance, or public display.” The song was therefore “published” as the result of having given copies to numerous radio and/ or nightclub disc jockeys for the purpose of playing and/or promoting the song.

Multiple registrations for one work are allowed under only limited circumstances. The second registration would have been allowed had the Copyright Office known of the earlier registration for the unpublished work because that is an exception to the one registration rule, a re-registration upon publication of a previously unpublished work. However, the date of creation was incorrect, stated as 2006 when it was actually created in 2005, so the registration would not have issued had the Copyright Office known the information was incorrect.

The third registration was no good because there was not an exception that would have allowed this re-registration of a previously-registered work, plus the date of creation was also incorrect on this application.

The court was verily unhappy with the plaintiffs’ unwillingness to agree that it wasn’t proper to try to register the same work multiple times or to seek the Register’s opinion on the validity of the registrations:

Plaintiffs insist that the Court can ignore the fact that three registrations exist for the musical composition Hustlin’. Under Plaintiffs’ theory of the law, for which they have provided no authority, a claimant who has multiple registrations for a single work — each of which contains obvious and undisputed errors — can simply choose which registration satisfies the Act’s requirements prior to bringing suit. If the Court were to permit Plaintiffs to unilaterally adjudicate which registration is valid and, therefore, which one satisfies the Act’s requirements, the Court not only would be abdicating its own responsibilities but also would be, in effect, invalidating the other two registrations. This the Court cannot do without seeking the Register’s advice under § 411(b).

But whether the registration would have been refused isn’t the only consideration; § 411(b) also says that there has to be knowledge that the information was inaccurate. The plaintiff argued that this standard should be fraud or a material misrepresentation but the court didn’t agree:

Plaintiffs’ contention that a single work may have multiple, inaccurate, inconsistent registrations so long as: each filer never intended to defraud the Copyright Office; each filer was willfully blind to the actual facts attested to in the registration; and each filer did not have actual knowledge of prior registrations, is directly contrary to well-established copyright law.

The court described at length how the plaintiffs would have known that the information was incorrect – they knew when they wrote the songs and how and when they were distributed; that the claimants were wrong (i.e., the plaintiff’s theory of the case was that 3 Blunts and 4 Blunts didn’t exist so Roberts was the true copyright owner, yet 3 Blunts and 4 Blunts were listed as claimants); and they could have searched Copyright Office records to learn of the earlier registrations.

The court didn’t stop after deciding that the work wasn’t validly registered; it also explained why, even if the work was registered, plaintiffs still didn’t have standing as either legal or beneficial owners. I leave it to you to read the analysis, but the court concludes

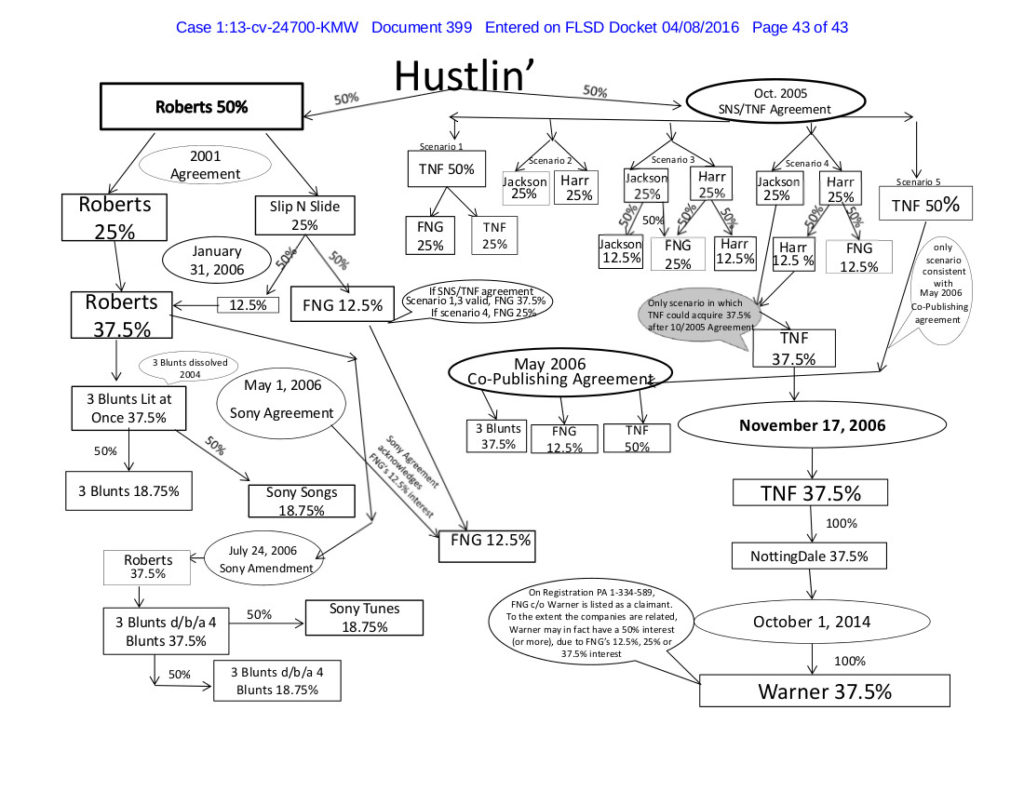

Unsurprisingly, given the numerous transfers outlined above, during his April 28, 2015 deposition, taken after more than a year of litigation, Harr testified that he did not know what his ownership share was in the exclusive rights:

Q: Okay. What’s the percentage ownership you have in Hustlin’?

A: Right now that’s kind of — we’re still deciding. It might be higher because right now we’re claiming, out total claim, both of us, is 37.5, but mind would be — I would have to look at it. It was — (witness mumbling). So 12.5 minus — 12.5. But I don’t agree with — I think it should be higher possibly. We’re trying to figure that out.Unfortunately, as of this date, neither Harr, nor Jackson, nor Roberts, nor TNF, nor FNG, nor Sony, nor Defendants, nor their counsel, nor the Court can ‘figure out’ who owns what with regard to the musical composition Hustlin’.”

There was also no evidence they were beneficial owners, i.e., an author who had parted with legal title to the copyright in exchange for percentage royalties based on sales or license fees:

The Court has not found in the voluminous briefing, nor have the Parties identified, any record evidence demonstrating any royalty payment to Roberts, Harr, or Jackson relating to the right to prepare derivative works of Hustlin’. Nor is there any evidence that Plaintiffs, themselves, are even entitled to royalties for the exploitation of Hustlin’. Roberts has not produced any royalty statements showing any royalties he received from 3 Blunts or FNG in exchange for any transfer of his ownership interest in Hustlin’. Likewise, Harr and Jackson have produced no royalty statements showing any royalties received from TNF or FNG in exchange for any transfer of any ownership interest in Hustlin.’ In addition, to the extent Harr and Jackson receive royalties for their compositions, both testified that all royalties are paid to TNF, not to Harr and Jackson. As Harr and Jackson explain, all royalties earned “from Hustlin’ (other than the writer’s share which is paid to me personally) are paid initially to Trac N. Field. Harr and I are paid by Trac N Field through draws or distributions.” And each of the agreements signed by TNF, 3 Blunts, Roberts, Harr or Jackson make clear that Roberts, Harr and Jackson do not have any right to authorize or create derivative works of Hustlin’; rather, that exclusive right belongs to Sony/ATV, FNG, and Notting Dale/Warner. In sum, there is no evidence that Harr, Jackson, or Roberts personally receive any royalties for the licensing or commercial exploitation of Hustlin’.

Roberts v. Gordy, No. 13-24700-CIV-WILLIAMS (S.D. Fla. April 8, 2016).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License

Leave a Reply