I previously wrote about a case, Uptown Grill, L.L.C. v. Shwartz, with some boobery in the sale of a single-locale restaurant. There were two relevant documents, a Bill of Sale and a trademark license agreement, entered into 16 days apart. The Bill of Sale was between seller Shwartz and Uptown Grill LLC in exchange for $10,000, and the license agreement was between Shwartz and Grill Holdings LLC for $1,000,000. An individual name Hicham Khodr owned both Upgtown Grill and Grill Holdings. The Bill of Sale had this unfortunate language:

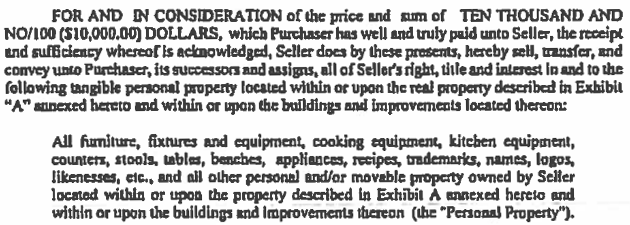

If you can’t read it, the Bill of Sale transfers:

[I]nterest in and to the following tangible personal property located within or upon the real property described in Exhibit “A” . . . and within or upon the buildings and improvements located thereon:

All furniture, fixtures and equipment, cooking equipment, kitchen equipment, counters, stools, tables, benches, appliances, recipes, trademarks, names, logos, likenesses, etc., and all other personal and/or movable property owned by Seller located within or upon the property described in Exhibit A annexed hereto and within or upon the buildings and improvements thereon.

The district court held that the Bill of Sale transferred, not just the trademark rights at the one locale, but all trademark rights everywhere. The Court of Appeals remanded because the district court went too far:

Unbidden by Uptown Grill, the district court went one step further. Uptown Grill expressly and repeatedly sought only a declaration that it owns the Camellia Grill trademarks within or upon the Carrollton Avenue location. The district court sua sponte concluded that, “as a secondary issue for this Court to address,” Uptown Grill owns all of the Camellia Grill trademarks. The court reasoned that since the Shwartz parties only used the trademarks at the Carrollton Avenue location, and since the trademarks within or upon that location were sold, then neither CGH nor any other affiliate retained an interest in any of the trademarks that are now used at other Camellia Grill locations. The court failed to explain the legal significance of the appellants’ allegedly geographically limited “use” of the trademarks. Instead, the court simply appears to have pursued to a logical conclusion its interpretation of the Bill of Sale….

In sum, while CGH may well be bound by a mis-drafted Bill of Sale, the court must consider whether Uptown Grill should be bound by its pleadings, representations in court, and practice with respect to a License Agreement for which its affiliate, Grill Holdings, paid a million dollars. At least, the court must take all facts and circumstances of the parties’ contractual relations, litigation tactics, and applicable trademark law into consideration before reinstating relief plainly beyond the plaintiffs’ pleadings. We therefore remand for further proceedings not inconsistent herewith.

In my prior post I argued that the rights outside of the one location weren’t transferred; there was a federal registration that the court never mentioned and, of course, the small matter of $1,000,000 paid for something.

What I also didn’t discuss before was the language of the Bill of Sale. While the appeals court affirmed that the trademarks were assigned in the Bill of Sale, it also recognized that this was probably an error, characterizing it as “mis-drafted.” Under US law we don’t have the latitude to outright change these kinds of mistakes though, as explained by the Court of Appeals:

The Bill of Sale expressly invokes Louisiana law. Under Louisiana law, “[w]hen the words of a contract are clear and explicit and lead to no absurd consequences, no further interpretation may be made in search of the parties’ intent.” La. Civ. Code Ann. art. 2046. Whether a contract is clear and unambiguous is a question of law. La. Ins. Guar. Ass’n v. Interstate Fire & Cas. Co., 630 So.2d 759, 764 (La. 1994) (citation omitted). “[A] contract is ambiguous when it is uncertain as to the parties’ intentions and is susceptible to more than one reasonable meaning under the circumstances and after applying established rules of construction.” In re Liljeberg Enters., 304 F.3d 410, 440 (5th Cir. 2002) (quotations and citations omitted). The court may not disregard any contract provision “under the pretext of pursuing its spirit” unless the provision is unclear or ambiguous, “as it is not the duty of the courts to bend the meaning of the words of a contract into harmony with a supposed reasonable intention of the parties.” Clovelly Oil Co., LLC v. Midstates Petrol. Co., LLC, 2012-2055, p. 5 (La. 3/19/13); 112 So.3d 187, 192.

But I can make an argument that the Bill of Sale was ambiguous. As pointed out by the plaintiff, the Bill of Sale is for “tangible personal property,” but the “trademarks, names, logos [and] likenesses” are intangible. The Court of Appeals noted that

First, where the specific provisions of a contract apparently conflict with the general provisions of a contract, the “specific controls the general.” Mazzini v. Strathman, 2013-0555, p. 10 (La. App. 4 Cir. 4/16/14); 140 So.3d 253, 259 (citation omitted). To the extent that “trademarks, logos, names, likenesses, etc.” conflicts with “tangible personal property,” the specifically listed property controls. Second, “[e]ach provision of a contract must be interpreted in light of the other provisions, and a provision susceptible of different meanings must be interpreted with a meaning that renders it effective rather than one which renders it ineffective.” Lewis v. Hamilton, 94-2204, p. 6 (La. 4/10/95); 652 So. 2d 1327, 1330 (citing La. Civ. Code Ann. arts. 2049, 2050). A finding that the trademarks are not transferred would improperly render the “trademarks, names, logos, likenesses, etc.” language ineffective. This is especially unnecessary in light of the other contractual provisions that broadly transfer “Personal Property,” a category covering the trademarks.

But for every interpretive principle there is a contrary one; in this case noscitur a sociis, “that a word is known by the company it keeps, while not an inescapable rule, is often wisely applied where a word is capable of many meanings in order to avoid the giving of unintended breadth….” Under this principle I can reconcile “trademarks, names, logos and likenesses” with “tangible property” because the trademarks are manifested in tangible form on the property being transferred, like menus, signs and place mats. I can see an unsophisticated contract drafter, one not well-versed in trademark law, using a poor word choice to explain that the restaurant didn’t have to rebrand.

But it’s too late; the court of appeals held that the district court’s conclusion that there was an assignment of trademarks was correct, the district court only erring on the geographic scope. We’ll see, but I still have a hard time seeing that the Bill of Sale transferred all rights everywhere.

Uptown Grill, L.L.C. v. Shwartz, No. 15-30617 (5th Cir. March 23, 2016).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Leave a Reply