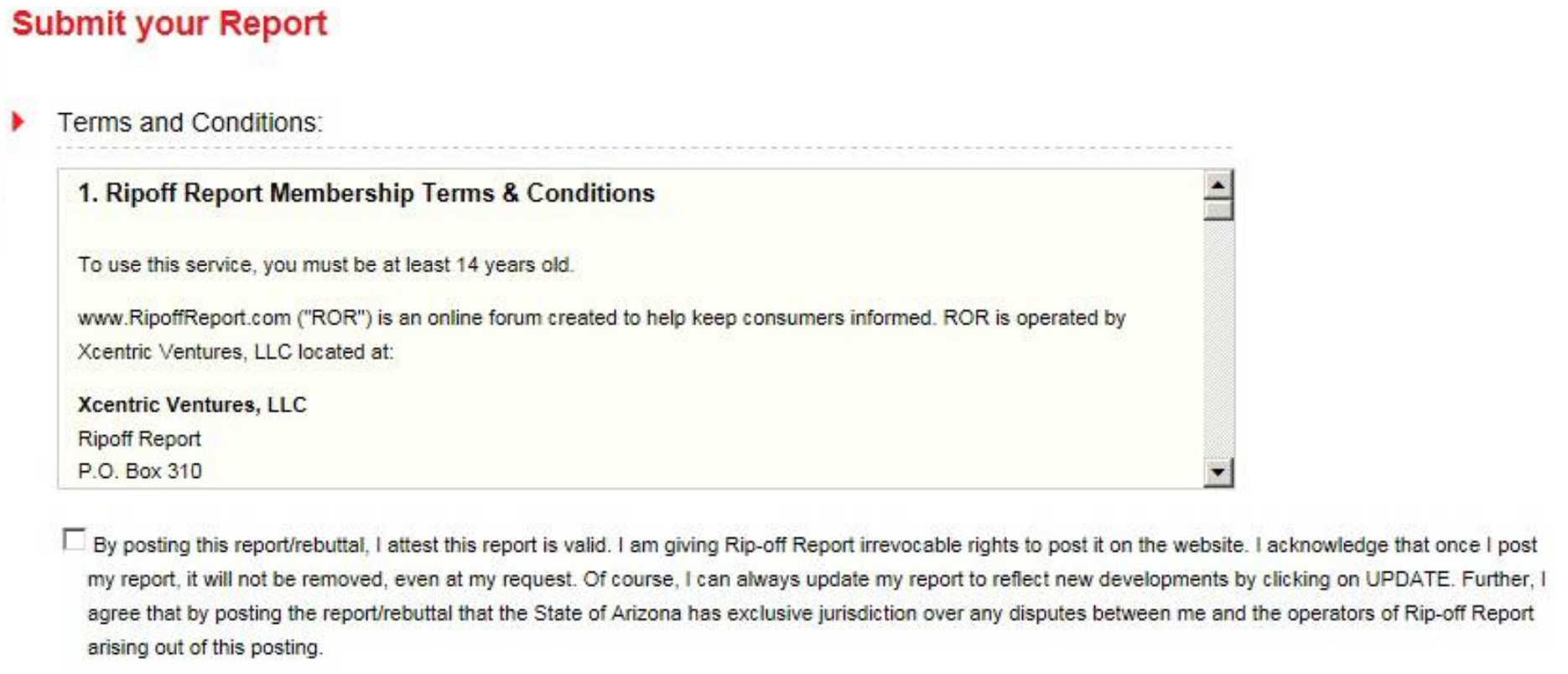

I asked whether the below “Submit” page, used when one posts a review on Rip-Off Report (owned by defendant Xcentric), transferred an exclusive license in the submitter’s copyright:

If you were to use the scrollbar on the right, you would find this grant:

“By posting information or content to any public area of www.RipoffReport.com, you automatically grant, and you represent and warrant that you have the right to grant, to Xcentric an irrevocable, perpetual, fully-paid, worldwide exclusive license to use, copy, perform, display and distribute such information and content ….”

Underneath the scroll area is a check box with this text:

“By posting this report/rebuttal, I attest this report is valid. I am giving Rip–Off Report irrevocable rights to post it on the website. I acknowledge that once I post my report, it will not be removed, even at my request….”

And the answer is … maybe?

As background, attorney Richard Goren was unhappy with two reports about him that were posted on Rip-Off Report. He sued the complainer, Christian DuPont, and, in a default judgment, the court assigned the copyrights to Goren and appointed Goren as attorney-in-fact, which allowed Goren to execute the assignment documents. Goren then later assigned the copyrights to plaintiff Simple Justice. (More about the default judgment in a moment.) In the instant case, Simple Justice sued Xentric on several theories, relevant here are the counts for copyright ownership and infringement. If DuPont had granted an exclusive license* to Rip-Off Report, then the court couldn’t have later assigned the same rights to Goren.

The fundamental struggle for the court was that the checkbox wasn’t clearly labeled as assent to the Terms of Service, the text in the box immediately above it. It didn’t say “by checking this box you agree to the Terms of Service above and that …”; rather, the check box could be interpreted as agreeing only to the text next to the box.

So what to do? The court sets off on the hopeless task of trying to decide whether this is a “clickwrap” or “browsewrap” license. I have come to agree with Venkat Balasubramani and Eric Goldman’s view that this has become a meaningless distinction, and what we should do instead is just look at basic contract formation principles.

But the court forges on. This wasn’t “clickwrap” because of the defect:

Xcentric construes the terms and conditions as a clickwrap agreement, but the user never affirmatively indicates his agreement. The terms accompanying the checkbox do not state that “I agree to the terms and conditions” or other such language indicating express accord. By checking the box, the user agrees only to the terms accompanying the checkbox. This means that the terms and conditions, including the grant of an exclusive license, which is paramount to a copyright transfer, constitute a browsewrap agreement.

So the court then looks at whether there was assent to this “browsewrap” agreement:

[B]rowsewrap agreements do “not require the user to manifest assent to the terms and conditions expressly. A party instead gives his assent simply by using the website.” [Nguyen v. Barnes & Noble Inc., 763 F.3d 1171, 1176 (9th Cir. 2014)]. Clickwrap agreements are generally upheld because they require affirmative action on the part of the user. Because no affirmative action is required by a website user to agree to the terms of a browsewrap contract other than his or her use of the website, the determination of the validity of a browsewrap contract depends on whether the user has actual or constructive notice of a website’s terms and conditions. If there is no evidence of actual notice, then the website owner must show that it “put[ ] a reasonably prudent user on inquiry notice of the terms of the contract.” Nguyen, 763 F.3d at 1177.

(Some internal citations, brackets and quotation marks omitted).

But here’s the problem. We’re not looking for assent to just any contract, but an assignment of a copyright. That requires a writing. Ngyuen was about arbitration, and whether there was assent to a contractual provision about arbitration is not the same question as whether there is a writing signed by the assignor of the copyright.

But that wrinkle doesn’t slow down the court. Based on the design of the webpage “the Court concludes that a reasonably prudent user was on inquiry notice of the terms and conditions associated with the [Rip-Off Report], and, therefore, the transfer of copyright ownership was valid.”

But how could that be right? How can the court find that (1) there was no signature, or signature equivalent, because the checkbox did not refer to the Terms of Service that conveyed the exclusive license and yet (2) there was an assignment? Yup, that’s just irreconcilable.

As a backstop, the court also found that the checkbox text granted “an irrevocable right to Xcentric to post [DuPont’s] report on the website,” which, “if the browsewrap agreement were somehow invalid” was “at the very least, a non-exclusive license to publish the Reports.”

So the conclusion:

The Court concludes that DuPont transferred copyright ownership to Xcentric by means of an enforceable browsewrap agreement. Xcentric is thus entitled to summary judgment as to Count I (declaratory judgment as to copyright ownership) and Count II (copyright infringement). Moreover, even if the browsewrap agreement were considered invalid and DuPont retained ownership of the copyrights to the Reports, he nonetheless granted a non-exclusive license to Xcentric and, therefore, he waived his right to sue Xcentric for infringement where its use did not exceed the scope of that license. The latter scenario also requires summary judgment for Xcentric as to Count II.

I don’t know whether this was a valid assignment or not because the court answered the wrong question. The right question was “is this checkbox a signature agreeing to the Terms of Service”? The court said not, but while looking at it through the wrong lens. The court talked a lot about how everyone would understand scroll bars and hyperlinks and layout in the context of assent, so if one was looking at it in terms of a signature, rather than assent, the outcome might have been different. Eric Goldman says “I’m confident that a super-majority of users understood that they were agreeing to the terms when they saw that scrollbox and proceeded to post,” and I agree. So I don’t think it would be a stretch to say that this could be a signature to an assignment.

Or, alternatively, would the checkbox terms suffice for a copyright assignment? They might, there’s a lot of law around the language of assignment, but that wasn’t explored by the court.

So, in conclusion—who knows. It was just the wrong question and therefore examined using the wrong law.

And the bonus issue: The district court’s assignment of the copyright to Goren in a default judgment is unlawful under Section 201(e), which prohibits an act “to seize, expropriate, transfer, or exercise rights of ownership with respect to the copyright, or any of the exclusive rights under a copyright” by a governmental body, except in bankruptcy, provided that the owner of the copyright is the original individual author who has never transferred it. (Some history here.) The court’s transfer of the DuPont copyrights was therefore ineffective.

Technology & Marketing Law Blog view of the case here.

Small Justice LLC v. Xcentric Ventures LLC, No. 13-cv-11701 (D. Mass. March 27, 2015).

- I use the same language that the grant clause uses, “exclusive license,” although the grant includes the right to “use, copy, perform, display and distribute” the content. Further, not in the opinion but on the current Rip-Off Report Terms of Service page, the grant continues “and to prepare derivative works of, or incorporate into other works, such information and content, and to grant and authorize sublicenses of the foregoing.” Although called a “license,” it doesn’t look like there are any rights that the submitter will have retained, so this is a full-blown assignment.

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Leave a Reply