As I’ve written about before, Sybersound is a 2008 Ninth Circuit decision that was not well-received by copyright authorities. We now have a second Ninth Circuit opinion interpreting Sybersound that undoes the original harm.

The decision is Corbello v. DeVito, the case that just keeps on giving for someone who writes about copyright ownership. It all starts with an unpublished authorized biography of Four Seasons member Tommy DeVito written by Rex Woodard. Rex Woodard passed away, so his wife and heir, plaintiff Donna Corbello, now owns any rights Woodard had in the biography. This long-running lawsuit is the result of the commercial success of the Broadway play Jersey Boys, with Corbello alleging that the play is a derivative work of the book and for which she is therefore entitled to royalties.

When we first visited the case, there was a dispute over ownership of the copyright in the biography, with both DeVito and Corbello claiming sole ownership. The court held that Woodard and DeVito were joint authors of the work, a decision that does not appear to have been appealed. Now we follow the money.

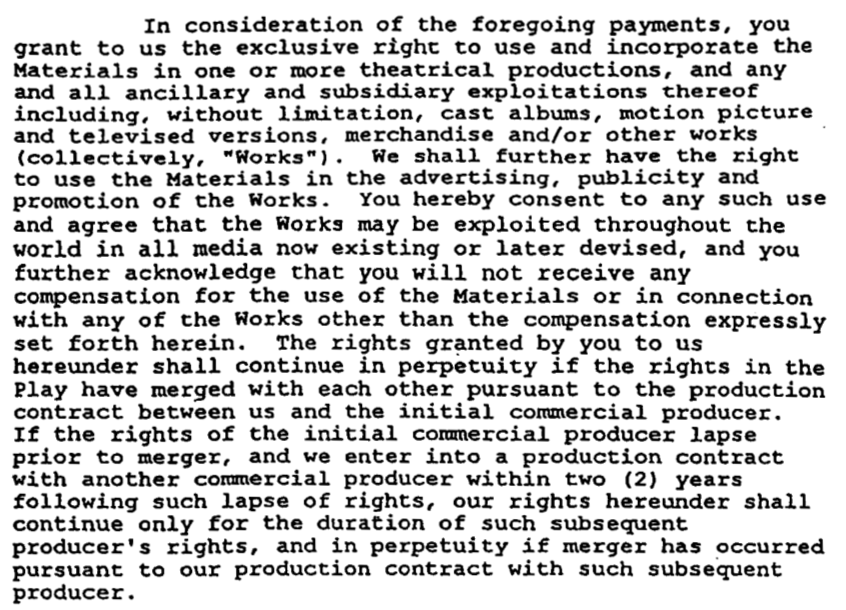

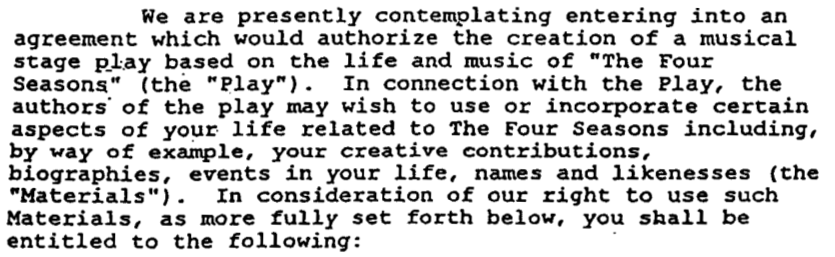

In 1999 DeVito granted his co-performers, Valli and Gaudio, the right to exploit—something. Both the “something,” that is, whether the rights granted included the copyright in the book, and what the contours of the grant were—assignment, exclusive license or non-exclusive license—were in dispute. The grant was of the “exclusive right to use and incorporate the Materials in one or more theatrical productions,” with a reversion:

The “Materials” were defined as “certain aspects of your life related to the Four Seasons including, by way of example, your creative contributions, biographies, events in your life, names and likenesses.”

One of Corbello’s the appellees’ theories was that, since DeVito was a joint owner and not the sole owner of the book copyright, Sybersound dictates that he could only have granted a non-exclusive license in the biography. Indeed Sybersound says that pretty clearly. In Sybersound, TVT was a joint owner of copyrights and granted its rights exclusively to Sybersound Records. Sybersound Records then sued unlicensed defendants, but its case was dismissed for lack of standing:

Thus, unless all the other co-owners of the copyright joined in granting an exclusive right to Sybersound, TVT, acting solely as co-owner of the copyright, could grant only a nonexclusive license to Sybersound because TVT may not limit the other co-owners’ independent rights to exploit the copyright.

Sybersound Records v. UAV Corp., 517 F.3d 1137 (9th Cir. 2008).

But the Ninth Circuit has now pivoted on Sybersound, as it should have. The district court in Corbello v. DeVito suggested a rethinking of Sybersound might be in order. In holding that what DeVito had granted was a “selectively exclusive license,” not a non-exclusive license, the district court was optimistic about a Ninth Circuit revisit of Sybersound:

Surely the Ninth Circuit will clarify that it meant something like this if given the chance, and perhaps it will have the chance in the present case. In any case, this Court is confident that the Sybersound court is guilty at most of imprecise syntax or some minor equivocation, as opposed to outright copyright-law heresy.

And the Ninth Circuit did clarify—sort of:

Appellees argue that our precedent, Sybersound Records, Inc. v. UAV Corp., 517 F.3d 1137 (9th Cir.2008), prohibits a co-owner of a copyright, such as DeVito, from transferring that right without permission from his co-owner, in this instance, Corbello. But that argument stretches Sybersound’s holding too far.

…[A]n assignment or exclusive license from one joint-owner to a third party cannot bind the other joint-owners or limit their rights in the copyright without their consent. In other words, the third party’s right is “exclusive” as to the assigning or licensing co-owner, but not as to the other co-owners and their assignees or licensees. As such, a third-party assignee or licensee lacks standing to challenge the attempted assignments or licenses of other copyright owners.

…

Therefore, Sybersound presents no obstacle to Devito’s exclusive transfer of his derivative-work right to Valli and Gaudio under the 1999 Agreement.

As I read it, the Court of Appeals is saying that the law does not give a co-owner the right to dictate how the other co-owners may dispose of their copyright interest. That would be a reasonable reading of Sybersound if that’s what the Sybersound case was about, but it wasn’t. There was no discussion whatsoever in Sybersound about what the non-party co-owners had done with their share, it was only about what TVT had granted to Sybersound Records. Nevertheless, we appear to have a course correction on the rights of joint ownership, at least outside of a 12(b)(1) motion for lack of standing.

But the Court of Appeals differed with the district court on the legal significance of the DeVito-Valli/Gaudio transaction. The district court characterized it as an exclusive license but the Court of Appeals said it was an assignment (as William Patry points out, in copyright an assignment and an exclusive license are the same thing):

Despite concluding that the Agreement’s inclusion of “biographies” in the definition of “Materials” sufficiently included the Work so as to grant Valli and Gaudio an exclusive license to use it in producing the Play, the district court nevertheless found that the Work fell outside of the Agreement’s use of “biographies” for the purpose of transferring ownership of a copyright interest in the Work. We are not persuaded by the district court’s interpretation.

…

Pursuant to the 1999 Agreement, Devito granted Valli and Gaudio the “exclusive right to use” his “biographies,” unambiguously including the Work, to create a play. Such play constitutes a “derivative work,” the right to create which resides in each copyright holder of the underlying work and may be transferred by that holder to a third party. Thus, in granting this exclusive right to create, whether classified as an exclusive license or an assignment, the 1999 Agreement constitutes a transfer of ownership of Devito’s derivative-work right in the Work to Valli and Gaudio.

So what has seven years of litigation thus far accomplished? To decide that the owners of the copyright in the book are Corbello, Valli and Gaudio. That’s it. The dissent (which would have held DeVito granted a non-exclusive license based on the binding precedent of Sybersound) points out we haven’t even reached the question of whether the stage play used the book, i.e., is a derivative work of the book. It’s by no means a foregone conclusion; the play producers had access to many materials, including the original performers, and proving substantial similarity between the expression of the book and the play, not just the facts, is going to be tough. There was also a failed first effort to mount a show, and a question of fact about whether the copyright reverted to DeVito under the reversionary provisions of the letter agreement. So assuming there is a case to be made that Corbello is entitled to some payment on some theory, figuring out how much will be another decade of litigation.

Corbello’s original intention, before all of this started, was to published her late-husband’s book and get some bounce from the then-new Broadway show. In the process she learned that the show producers had access to the book when developing the script and a whole new pot of money appeared, over $1.7 billion worldwide by one account—who says Broadway is dead?

But in the meantime we’re getting all this ownership law goodness out of it.

Corbello v. DeVito, Nos. 12-16733, 13-15826 (9th Cir. Feb. 10, 2015).

23 February 2015: Parties corrected.

Leave a Reply