I’ve written about MemoryLink Corp. v. Motorola Solutions, Inc. in the past (recursive link). Peter Strandwitz and Bob Kniskern, owners of plaintiff Memorylink, had collaborated with defendant Motorola Solutions on the development of a handheld camera that could wirelessly transmit and receive video signals. Standwitz and Kniskern trusted Motorola Solutions with filing patent applications on the invention, so Motorola Solutions’ attorney sent a letter confirming with the inventors the scope of the invention and that they were co-inventors with two Motorola Solutions employees. All four inventors executed an assignment transferring their rights to both Motorola Solutions and Memorylink.

Before the patent issued, Memorylink had its own law firm file a divisional of the application listing the same inventors but, a few years later and after investigation by another attorney, decided that the Motorola Solutions employees had not been inventors on the original patent. Memorylink sued Motorola Solutions for patent infringement and in tort, also asking that the assignment be declared void for absence of consideration. All the claims were time-barred except for the contract claim. But the contract claim ultimately was not a successful theory either.

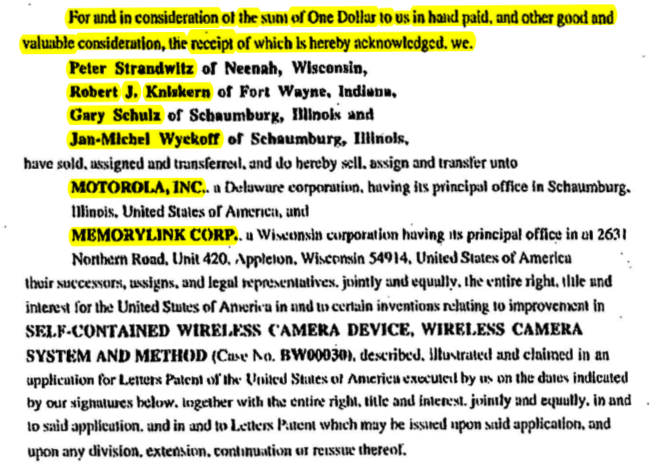

Illinois contract law applied, under which a court only examines whether there is consideration, not its adequacy, unless the amount is “so grossly inadequate as to shock the conscience.” The assignment recited consideration, specifically:

(Highlighting in the court’s documents.) If you can’t see the image, the assignment says “For and in consideration of the sum of One Dollar to us in hand paid, and other good and valuable consideration….” Memorylink asserted this language was “mere boilerplate” for purposes of recording at the Patent Office, and that the intended consideration was a mutual sharing of patent ownership between Memorylink and Motorola Solutions. But, Memorylink argued, that consideration failed since no Motorola Solutions employees were actually inventors.

Under Illinois law “an agreement, when reduced to writing, must be presumed to speak the intention of the parties who signed it…. It is not to be changed by extrinsic evidence.” So the assignment was valid because it recited consideration: “the use of boilerplate language does not make the stated consideration invalid or nonexistent.” In addition to the recitation there was an actual exchange of consideration too, whatever ownership interest the Motorola Solutions employees had was transferred to Memorylink. That the Motorola Solutions inventors may ultimately have no inventorship interest is not the same as the absence of consideration at the time of the assignment, “a party assigning patent rights before a patent application is filed or during patent prosecution cannot guarantee that a patent will issue or, even once issued, that the patent will not be later invalidated.” Considering extrinsic evidence there was further consideration, namely Motorola’s representation on prosecution of the patent application. As to the value of the consideration, “we do not find the consideration to be so insufficient as to shock the conscience of the court; we thus decline to examine the adequacy of the consideration.”

The assignment issue is muddied by what appears to be some underhanded maneuvers by Motorola Solutions, but the fundamental principle that there was consideration isn’t remarkable. If you unmuddy it and assume that the Motorola Solutions inventors were true inventors, but only on some claims that were ultimately unpatentable, that was the bargain that Memorylink struck, taking that risk. So the better theory for the alleged wrongdoing is tort, but there is no substantive decision on the possibly tortious behavior because the claims were time-barred. Motorola Solutions may have gotten away with something, but that’s why there is a statute of limitations.

Memorylink Corp. v. Motorola Solutions, Inc., No. 2014-1186 (Fed. Cir. Dec. 5, 2014).

Memorylink Corp. v. Motorola Solutions, Inc., No. 08 C 3301 (N.D. Ill. Aug. 15, 2013).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Leave a Reply