Whether a license provision is categorized as a “condition” or a “covenant” will determine what remedies are available. Noncompliance with a covenant of the agreement is a merely a breach, so you get contract remedies. If the noncompliance means you failed to satisfy a condition, then you have no license and are subject to infringement remedies, most notably injunctive relief.

There are a couple of leading cases that discuss the distinction, MDY Indus., LLC v. Blizzard Entm’t, Inc., 629 F.3d 928 (9th Cir. 2010) opinion amended and superseded on denial of reh’g, 09-15932 (9th Cir. Feb. 17, 2011) and Jacobsen v. Katzer, 535 F.3d 1373 (Fed. Cir. 2008). But the most thorough explanation, albeit with what I believe is a troubling outcome, is in a recent district court opinion in Sleash, LLC v. One Pet Planet, LLC. It’s a trademark license case, but really applicable to any license interpretation.

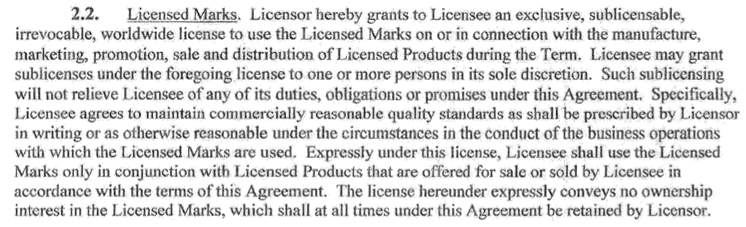

Plaintiff-licensor Sleash and defendant-licensee One Pet Product (OPP) had a manufacturing and distribution agreement that included the grant of a trademark license. This is the language in question:

If you can’t read it, the relevant portion is:

Licensor hereby grants to Licensee an exclusive, sublicensable, irrevocable worldwide license to use the Licensed Marks on or in connection with the manufacture, marketing, promotion, sale and distribution of Licensed Products during the Term. … Specifically, Licensee agrees to maintain commercially reasonable quality standards as shall be prescribed by Licensor in writing or as otherwise reasonable under the circumstances in the conduct of the business operations with which the Licensed Marks are used. Expressly under this license, Licensee shall use the Licensed Marks only in conjunction with Licensed Products that are offered for sale or sold by Licensee in accordance with the terms of this Agreement. The Licensee hereunder expressly conveys no ownership interest in the Licensed Marks, which shall at all times under this Agreement be retained by Licensor.

OPP never made products that were satisfactory to Sleash. There was a failed attempt at terminating the agreement (folks, give notice as described by the terms of agreement AND use words like, I dunno, maybe “terminate”). The backup theory was that OPP’s failure to meet quality standards meant that the products sold were not licensed and therefore infringing. It was a question of whether the license grant was the first sentence only with the rest of the paragraph stating covenants (as argued by OPP) or whether the subsequent provisions in the paragraph were also conditions of the grant (as argued by Sleash).

Here’s the court’s explanation of how you tell conditions and covenants apart (internal quotation marks and citations omitted):

A covenant is a contractual promise, i.e., the manifestation of intention to act or refrain from acting in a specified way, so made as to justify a promise in understanding that a commitment has been made. No special form of words is necessary to create a promise. Instead, a court determines from a fair interpretation of the language of the instrument whether the parties intended a promise.

In contrast, a condition precedent constitutes facts and events, occurring subsequently to the making of a valid contract, that must exist or occur before there is a right to immediate performance, before there is a breach of contract duty, and before the usual judicial remedies are available. The intent of the parties, to be ascertained from a fair and reasonable construction of the language used in light of all the surrounding circumstances, determines whether a provision in a contract is a condition or a covenant….

Although promises and conditions are different, the distinction can be blurred, and the determination whether a provision states a promise, a condition, or both, can be difficult. Given this difficulty, the Oregon Court of Appeals noted that the following analysis is helpful:(1) a promise is always made by one of the parties to the contract whereas an event can be made to operate as a condition only when the parties to the contract agree that it shall operate as such, except in those cases where conditions are created by law; (2) the purpose of a promise is to create a duty in the promisor, whereas the purpose of a condition is to postpone a duty in the promisor; (3) when a promise is performed, the duty is discharged; but where a condition occurs, the quiescent duty is activated; and (4) when a promise is not performed, a breach of contract occurs and the promisee is entitled to damages.

A court will not imply that a covenant is a condition unless the parties use clear and unambiguous language. This canon of construction avoids the harsh effect of forfeiture which may result from a failure of a condition precedent, and does not result in a minor failure to perform exactly as called for, wholly destroying all rights under the contract. Another reason contract conditions are generally disfavored is that promises set the parties’ liability from the outset—and conditions therefore will not be found unless there is unambiguous language indicating that the parties intended to create a conditional obligation.

Applying this standard, the court held that the quality control provisions in the agreement were a covenant by the defendant, not a condition of the license. Sleash argued that everything in the paragraph had to be performed “in accordance with the terms of this Agreement,” but that was too far a stretch:

The relevant full sentence reads: “Expressly under this license, Licensee shall use the Licensed Marks only in conjunction with Licensed Products that are offered for sale or sold by Licensee in accordance with the terms of this Agreement.” The most natural and reasonable reading of this text is that OPP may only use the Licensed Marks on Licensed Products, which both parties concede OPP did in this case. Moreover, this sentence uses text indicating a promise and not a condition. … OPP is simply promising not to use the Licensed Marks on anything other than Licensed Products as defined by the License Agreement.

Second, .. the limiting clause cited by Sleash does not expressly reference Section 5.4. Sleash argues that grant clause in the License Agreement is conditioned on OPP’s compliance with Section 5.4 of the License Agreement which governs the “Input on Materials” and provides that the parties “jointly approve the materials to be used in manufacturing the Licensed Products.” Nowhere in Section 2.2, however, is Section 5.4 referenced ….

Third, Sleash’s argument is further undermined when considered in light of the surrounding context. A sentence in the middle of Section 2.2 and not cited by Sleash explicitly references quality standards. That sentence reads: “Specifically, Licensee agrees to maintain commercially reasonable quality standards as shall be prescribed by Licensor in writing or as otherwise reasonable under the circumstances in the conduct of the business operations with which the Licensed Marks are used.” The phrase “agrees to maintain” constitutes a promise and does not condition OPP’s use of the Licensed Marks on Sleash’s prior approval….

The court also considered a defensive naked license argument, that is, a claim by Sleash (and I may be rewriting its argument here, but it’s how it makes sense to me) that Sleash must have imposed quality control standards as part of the grant or else it would risk naked licensing. The court didn’t agree though; one can avoid a naked license by actually exercising control, so the failure to include quality control terms as part of the license grant wasn’t fatal to the license agreement.

I agree this is suboptimal drafting, but it’s not THAT bad, particularly if written by a general business lawyer instead of a licensing lawyer. I think it’s too fine a distinction to say that a fundamental aspect of a trademark license, quality control, isn’t a condition of the license because of some hypertechnical distinction between, for example, the words “agrees to maintain” and “provided you maintain.” I also think the naked licensing argument was on the right track although perhaps not understood by the court: the point is that the doctrine of naked licensing is a demonstration that quality control is part and parcel of the license grant because, taken to an extreme, in its absence there is no trademark to grant a license to.

But lesson learned—always make your grant clause one very long sentence and use the words “subject to” a lot.

Sleash, LLC v. One Pet Planet, LLC, No. 32:14-cv-00863-ST (Aug. 6, 2014).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Leave a Reply