Not necessarily wrong, but harsh. The outcome is clearly contrary to the contracting parties’ intent, and a third party, an accused infringer, reaps the benefits.

Non-party Roman Martinez, Sr. was the author of two songs, Buscando Un Cariño and Morenita de Ojos Negros. On June 5, 1981, he and his band El Grupo Internacional de Ricky and Joe (which included his children) recorded, at defendant Hacienda Records & Recording Studio, 10 songs for an 8-track tape and 45s. Buscando and Morenita were two of the songs on the 8-track. Martinez paid $1900 for the session and received 300 8-tracks and 300 45s that the band passed out and sold at their concerts: “There wasn’t … much money made in this. Almost all, if not all, of the 45 singles were used as promotion[s]. Pretty much the same thing for the 8-tracks. [Some] sold, but most were given as promotion.”

About six months later Martinez and his band recorded another 8-track at the same studio, and a few days after that Martinez and his kids entered into an “Option Agreement” with the studio that gave Hacienda the right to promote and distribute – well, something; the parties dispute whether the distribution right includes the earlier-recorded Buscando and Morenita.

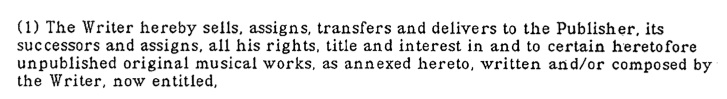

Fast forward to 1994, when Martinez and some of his kids are now performing as The Hometown Boys. The Hometown Boys made a new recording of Morenita and Martinez assigned the copyright to the song to the publishing company Musica Adelena. In 1999 the same thing happened with Buscando, that is, the band was going to re-record the song so Martinez assigned the copyright to Musica Adelena. Both Songwriters Contracts used this language:

If you can’t read it, it says:

(1) The Writer [Martinez Sr.] hereby sells, assigns, transfers and delivers to the Publisher, its successors and assigns, all his rights, title and interest in and to certain heretofore unpublished original musical works, as annexed hereto, written and/or composed by the Writer, now entitled,

stating the name of each song underneath it.

In 2000 Musica Adelena sold all the rights in its song catalog to plaintiff Tempest Publishing, Inc. The agreement was clear that the copyrights to Buscando and Morenita were transferred.

Tempest discovered that Hacienda was selling albums using the 1981 recordings of the two songs. And we have a lawsuit.

You’d think the dispute would be over the scope of Hacienda’s license to the two works, but you’d be wrong. The problem is with the assignment of the copyright from Martinez to Musica Adelena. The assignment was of “certain heretofore unpublished original musical works,” only there weren’t any such thing—both Buscando and Morenita had been published before Martinez assigned the copyright.

State law, in this case, Texas law, governs the construction of copyright assignments. Under Texas law, the instrument will be deemed to express the objective intention of the parties. And if the agreement is worded so the court can ascertain a certain or definite meaning, it is not ambiguous.

Under this standard, the Songwriters Contract was not ambiguous. Martinez testified that he thought “unpublished” meant he had not previously entered into a publishing agreement but the court didn’t buy it:

Under the Copyright Act, “publication” is a defined term. See 17 U.S.C. § 101 (” ‘Publication’ is the distribution of copies or phonorecords of a work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending.”); compare 17 U.S.C. § 408(b)(1) (“[T]he material deposited for registration shall include … in the case of an unpublished work, one complete copy or phonorecord[.]”), with 17 U.S.C. § 408(b)(2) (“[T]he material deposited for registration shall include … in the case of the published work, two complete copies or phonorecords of the best edition[.]”). Commonly used, to “publish” means “to prepare and produce for sale”; “to make generally known”; or “to disseminate to the public.” Merriam Webster, Merriam–Webster.com, available at http:// www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/publish.

Martinez’s testimony as to his subjective understanding of the term “published” is inconsistent with its meaning under both the Copyright Act and common usage. The agreements are not ambiguous, and the court cannot use parol evidence to create an ambiguity. Under the agreements, Musica Adelena, and therefore Tempest, did not acquire rights to the previously published songs, including the two at issue. Tempest cannot sue Hacienda for infringement for its use of the 1981 versions of those two songs under the Copyright Act.

Hmmm. Martinez’s understanding of “published” is quite colorable in the music industry, though, where a “publisher’s agreement” is a term of art used specifically for the composition rights. Martinez might also not have appreciated that producing and selling a sound recording is “publishing” the underlying composition too.

But it didn’t matter to the court; the songs were published. There was no mutual mistake since Musica Adelena knew what “unpublished” meant. And a unilateral mistake does not warrant reforming a contract absent inequitable conduct.

The court did a nice job shooting down a Billy-Bob Teeth theory. It’s actually the Eden Toys theory (but “Billy-Bob Teeth” is so much more fun), that is, a defense that has become broader and broader and now, when unexamined, stands for the proposition that a defendant doesn’t have standing to challenge an earlier transfer that the parties to the agreement don’t themselves contest. The court examined the original facts of Eden Toys, where the exclusive license at issue had been an informal one later memorialized in writing:

Tempest’s reliance on this line of cases is misplaced. Eden Toys is important, but limited. Under that case, an “after-the-fact writing can validate an agreement from the date of its inception, at least against challenges to the agreement by third parties.” But Eden Toys allows a prior, otherwise valid, agreement that does not satisfy § 204 to transfer the copyright interests at issue if an after-the-fact writing memorializing that agreement does satisfy § 204.

…

This case is different…. When, as here, the earlier agreement satisfied the § 204(a) writing requirement from the outset, Eden Toys does not affect the analysis or outcome.

So we have a harsh outcome for Tempest, even though it seems pretty clear that Martinez meant to assign the copyright in the two songs to Musica Adelena. The court recognized the harshness, but that can’t change the outcome:

Neither result the parties advocate is without problems…. The approach Hacienda takes, which this court finds required under the Copyright Act and case law, does present the problem of allowing a third-party to avoid liability for its alleged infringement of a transferred copyright even when the contracting parties agree that they wanted to transfer that copyright. The approach Tempest takes, which this court finds inconsistent with the Copyright Act, allows parties who have agreed in writing to transfer a specified copyright interest to later revise that agreement to expand the interests they transferred through declarations and oral testimony and then seek damages for intervening uses that allegedly infringe the expanded transfer. Tempest has not pointed the court to a case in which the Fifth Circuit has allowed a plaintiff to sue for copyright infringement without a document memorializing ownership of that right, as the statute requires.

A motion to reconsider was also denied: “The new assignment contracts Tempest drafted and Martinez signed after the court ruled on the motion for partial summary judgment are not newly discovered evidence; they are newly created evidence.”

While I applaud the court’s interpretation of Eden Toys, I’m very unsatisfied with this opinion. If under Texas law “we presume that the parties to a contract intend every clause to have some effect,” Heritage Resources, Inc. v. NationsBank, 939 S.W.2d 118, 121 (Tex. 1996), how can it be that an entire contract can be nullified, on summary judgment, by the use of a word that is susceptible to so many different meanings? The court didn’t even mention in passing “you know, this whole publication thing under copyright law is kind of a conundrum,” not to mention the specialized definition of a “publisher” in music copyright I mentioned above.

Tempest Publ’g, Inc. v. Hacienda Records and Recording Studio, Inc., No. H-12-736 (S.D. Tex. Nov. 7, 2013).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Leave a Reply