In Complex Systems, Inc. v. ABN AMRO Bank N.V., plaintiff CSI licensed its Banktrade software to an ABN AMRO (“ABN”) information technology subsidiary (“IT”) for use by the entire ABN enterprise. The case arose because ABN sold IT, along with the license, to Bank of America but ABN nevertheless continued to use the software. IT could have transferred the license to ABN before it was sold but the court ultimately concluded it hadn’t.

The court has now addressed ABN’s three remaining defenses. The decision starts with this fairly unusual confession:

This Opinion & Order seeks to provide both clarity and finality on the issue of liability in this long-pending and confused copyright infringement action. For a time, the Court itself was a victim of the confusion that has been rather pervasive in this action. Finally, however, the parties’ numerous submissions have provided the Court with much-needed clarity. The proverbial light bulb has finally been illuminated.

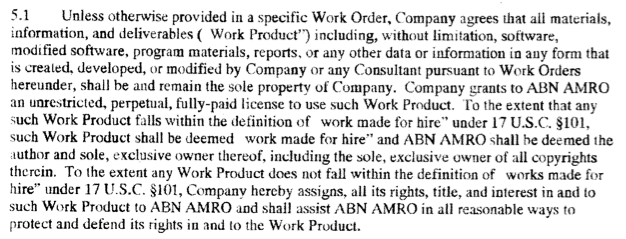

Defense #1 is that IT was actually a co-author of the software. Although the original license agreement for the Banktrade software was clear that CSI owned the copyright, there had also been a Professional Services Agreement between CSI and IT whereby CSI would customize the Banktrade software for IT. The agreement said this:

If you can’t read it, it says:

Unless otherwise provided in a specific Work Order, Company [i.e., CSI] agrees that all materials, information, and deliverables (“Work Product”) including, without limitation, software, modified software … that is created, developed, or modified by Company or any Consultant pursuant to Work Orders hereunder, shall be and remain the sole property of the Company. Company grants to [IT] an unrestricted, perpetual, fully-paid license to use such Work Product. To the extent that any such Work Product falls within the definition of [“]work made for hire” under 17 U.S.C. § 101, such Work Product shall be deemed [“]work made for hire” and [IT] shall be deemed the author and sole, exclusive owner thereof, including the sole, exclusive owner of all copyrights therein. To the extent any Work Product does not fall within the definition of [“]works made for hire” under 17 U.S.C. § 101, Company hereby assigns, all its rights, title, and interest in and to such Work Product to [IT] and shall assist [IT] in all reasonable ways to protect and defend its rights in and to the Work Product.

Everyone seems to concede that IT owned the copyright in some code that eventually made it into the Banktrade software and we’ll just go with it,* because none of it actually matters. ABN argues that “the record is clear and uncontradicted that [IT] is a co-author of a joint work in BankTrade,” but the court finds, in several different ways, that “even if this were so, it would not change the outcome of the instant motion.”

First, the court didn’t agree that modifications that might be owned by IT and ultimately included in the Banktrade software made the software a work of joint authorship—the amount was too small and the characterization of it as “work made for hire” meant it was just that, not a joint authorship.

Second, an ownership claim by IT would have been time-barred. CSI had registered the copyright as sole owner in 2008, putting IT on constructive notice that IT was not an owner at that point in time. Further, IT knew about CSI’s ownership claim as early as 2001 when the original license agreement was amended for “significant additional consideration.” Had IT been a joint owner, “one would not expect a one-way license agreement such as that here, but something akin to a cross-license, or other commercial arrangement.” Therefore, IT was on notice in 2001 that CSI claimed copyright ownership of the entire work, so a claim of joint ownership this late in the game was time-barred. (The case has a lengthy discussion of when a claim of ownership is time-barred, if you’re interested.)

Third, it wasn’t ABN’s place to raise the argument: “The law is clear that a party accused of infringement cannot defeat that claim by pointing to rights that another may have to the work in question.”** I don’t really get this; ABN was raising a license defense, i.e., IT was a joint author and it was a licensee of IT. If that had all been true, isn’t that a legitimate defense to raise?

ABN therefore lost on the joint authorship theory. Defenses #2 & 3 were that it was a direct licensee of CSI or IT, either expressly or impliedly, but the court wasn’t buying any of it. I don’t understand the reasoning, other than the one based on the fact that IT’s license wasn’t sublicenseable, so you’ll just have to figure it out for yourself.

What a mess. The opinion is confusing, in my opinion because ABN’s arguments border on frivolous. The court refers frequently to ABN’s ever-changing and inconsistent legal theories and the court struggles trying to reconcile the various arguments made at different times in the litigation.

The non-assignment of the license was just a flat-out business mistake and ABN is stretching legal arguments to their limits to try to avoid the clear intention of the parties at the time they entered into the original agreement, its several amendments, and the Professional Services Agreement. While the contractual documents are not models of clarity (and they often aren’t), CSI is undoubtedly the copyright owner of the software with a carve-out that IT, in theory, could own the copyright in a small piece of custom work. That’s it. At the time the contract was formed, and as reflected in many, many documents the court cites, no one would have thought there was any joint authorship or ownership of the entire product because of some minor customization. Arguments about joint ownership, implied licenses from CSI and sublicenses from IT are just hindsight litigation strategy almost entirely removed from the facts of the case. What bothers me is that the court did some overreaching to try to escape the contorted arguments, which will be vulnerable on appeal. And there are still damages to go too, so we could be seeing this case for a long time.

Complex Systems, Inc. v. ABN AMRO Bank N.V., No. 08 Civ. 7497(KBF) (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 25, 2013).

* There is also this footnote: “First, there is no evidence in the record suggesting that IT contributed to BankTrade 8 .0 in any substantial way; in fact, ABN’s Motion to Dismiss undermines such an assertion insofar as it argues that BankTrade 8.0 is largely derived from prior versions of the software. Second, ABN asserts (on behalf of IT) full co-authorship of BankTrade 8.0, yet IT only made specific, discrete modifications under the PSA. ABN fails to specify the extent to which these modifications impacted the Work as a whole.”

** This appears to be a modified application of the Billy-Bob Teeth defense, which is a theory that a defendant may not attack the plaintiff’s standing by alleging that there is a defect in the assignment of the copyright by a third party to the plaintiff. Here though, it’s a predecessor to the defendant itself that the defendant claims is the owner, so I don’t think the theory is apropos.

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Leave a Reply