What a mess. Add up ugly facts and a court that bought a frivolous and completely wrong argument (made without citation – because there aren’t any) and you end up with a fiasco. Here’s to appeals.

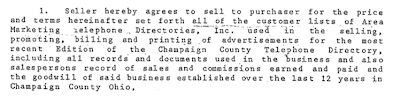

Non-party Herb Burkhalter had a yellow pages directory business he sold to co-defendants Steven M. Brandeberry and American Telephone Directories Inc. in 1994. Bradeberry and the company were jointly listed as “Purchaser” in the agreement. The agreement transferred customer lists, sales records, and the goodwill of the business.

All the assets of the business were to return to Burkhalter if the Purchaser defaulted. The unregistered “distinctive name, insignia and logo, entitled ‘AM/TEL’” was not immediately assigned, but rather was licensed to the Purchaser until the amounts due under the asset purchase agreement and trademark license were paid in full. Brandeberry and American Telephone Directories paid everything in full and therefore became the owners of the trademark.

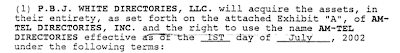

The business fell on hard times, so in 2002 an entity called “Amtel Directories, Inc.” sold the assets to P.B.J. White Directories, LLC. There was no Amtel Directories, Inc.; the entity was still legally American Telephone Directories, Inc. The defendants tried to make hay out the wrong party name but the court held this was an agreement with American Telephone Directories. In a one page Contract for Sale of Assets without any representations or warranties, the agreement transferred “all assets, in their entirety . . . and the right to use the name ‘AM-TEL DIRECTORIES’”:

The agreement was signed for “Amtel Directories, Inc.” by Brandeberry.

So do you see the problem? The trademark was originally assigned to two purchasers, Brandeberry and American Telephone Directories, but only American Telephone Directories assigned its assets to P.B.J. White Directories. (I note that the plaintiff argued that the license agreement was part of the assets transferred. The license contained the operative assignment for the trademark; thus the assignment of the trademark from Burkhalter to Bradeberry and American Telephone Directories was further assigned to P.B.J. White Directories, which seems like it should have taken care of the problem. But the court didn’t address this in its decision.)

In 2007, P.B.J. White Directories, LLC sold the business to plaintiff Yellow Book USA, Inc., including “all of the Company’s right, title and interest to the names ‘Amtel Directories.’”

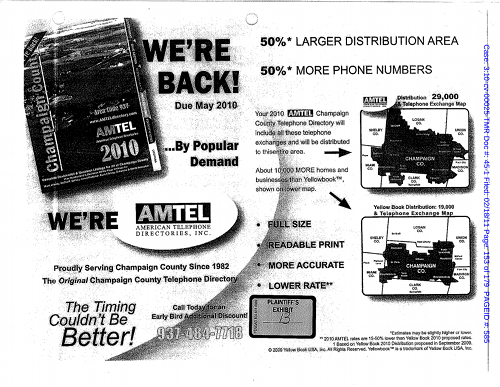

In 2009, Brandeberry went back into the “Amtel Directories” business, making mockups of the directories, business cards, envelopes and stationary using the Amtel mark:

Yellow Book sued him for trademark infringement and related claims.

It’s not an unreasonable position that the assignment of the mark was originally to two joint owners, American Telephone Directories and Brandeberry. I maintain that further investigation into whether indeed the trademark was owned by one or both was merited; looking at various factors relating to trademark ownership might disclose that over the course of time one or the other was actually controlling the quality of the goods and services and was the true owner.

Nevertheless, I can’t fault the court for holding that the assignment from so-called “Amtel Directories, Inc.” didn’t include an assignment of Brandeberry’s rights too. But correctly, Yellow Book also pointed out that Brandeberry didn’t use the mark from 2002 to 2009, so he abandoned any trademark rights he might have had. Sounds pretty slam-dunk, right? But the court goes well off the rails – I can only show the full injustice by quoting it:

| Brandeberry asserts that abandonment of a trademark by an owner can cause the owner to lose his right to sue a new user for infringement, but it does not deprive the owner of the right to use. However, Brandeberry has cited no caselaw in support of this assertion and the Court is unable to find any.

Courts have determined that trademark rights derive from the use of the trademark in commerce and not from the registration of the mark. Sands, Taylor & Wood Co. v. The Quaker Oats Co., 978 F.2d 947, 954 (7th Cir.1992). Further, the owner of a mark will lose the exclusive use of a mark if the owner fails to actually use the mark. Id. at 954-55. But it is not Brandeberry, in this case, who is claiming exclusive use of the AM/TEL name, marks and related assets. It is Yellow Book. Further, courts treat the abandonment of a trademark as a defense to an infringement claim. See Saxlehner v. Eisner & Mendelson Co., 179 U.S. 19, 31 (1900). And, again, it is not Brandeberry who has brought the infringement claim in this case. Abandonment is not Brandeberry’s defense. Thus, while Yellow Book’s argument that it is entitled to exclusive use of the AM/TEL name, marks and related assets because Brandeberry has abandoned the use of AM/TEL, may be relevant as a defense to a trademark lawsuit brought by Brandeberry, it is not relevant to a lawsuit that Yellow Book has brought. Yellow Book is not entitled to exclusive use of the AM/TEL name, marks and related assets because Brandeberry is also entitled to the use of these same AM/TEL names, marks and related assets. |

No. No. While abandonment often comes up as a defense to trademark infringement, abandonment is a loss of all rights entirely, for every purpose. The court said it was “unable to find any” case law – did the court not have a copy of Callman’s?

|

Abandonment is “in nature a forfeiture.” It destroys the trademark; it involves the “loss not only of the right to exclude others but also of the … right to use the name in trade.” The mark does not revert back to the assignor of the one who abandoned it; that assignor is in no better position than any other member of the public. . . .

Once a mark has been abandoned, “any other person has the right to seize upon it immediately … and thus acquire a right superior, not only to the right of the original user, but of all the world.” . . .

The issue of ownership after abandonment should be considered without reference to the prior ownership, whether the mark is thereafter appropriated by a stranger, or re-appropriated by the prior owner or the assignee of the prior owner. Thus, priority goes back only to the time the prior owner or his assignee re-appropriates the mark. Resumption after abandonment does not reinstate the abandoned rights. Therefore the rights of an intervening user are superior to those of a previous owner who abandoned and then resumed. |

(emphasis added). Or McCarthy’s?

Once the court found that Brandeberry was entitled to use the mark, Yellow Book’s likelihood of confusion claim failed.

| In this case, as determined above, Brandeberry has not given up his right to use the AM/TEL name, marks and related assets. Thus, Yellow Book cannot show that it is entitled to protection of the AM/TEL name, marks and related assets from their use by Brandeberry. |

Oh, where do I start? Of course Brandeberry abandoned the mark, he sold the company and stopped using the name because he fully intended that the business, including the trademark, be completely transferred.

Further, the court clearly has no concept of what a trademark is, that is, a SOLE source identifier. It is simply not a divisible asset. To allow two unrelated parties to use the same mark for the same goods in the same territory without one controlling the other is the very situation that trademark law is meant to prevent. The court’s conclusion is therefore necessarily wrong – whether because the mark was indeed fully assigned, or because Brandeberry abandoned it, but the outcome is entirely inconsistent with legal theory and policy. Yellow Book, please appeal.

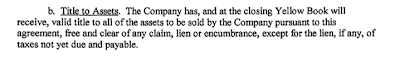

Bonus question: Yellow Book purchased “all of the Company’s right, title and interest to the name ‘Amtel Directories’ . . . ” and the Seller warranted that it owned “valid title to all of the assets to be sold by the Company pursuant to this Agreement . . . .”

Is there a claim for breach of warranty? I say not – the Company was only selling whatever “right, title and interest” it had and warranted that it had valid title to only that – it didn’t warrant that it owned exclusive rights to the transferred assets. This is a quitclaim, not a warranty deed. Check the indemnification clause yourself, but I don’t see any separate IP indemnification. I think the only claim is for breach of warranty, which isn’t going to work. Let me know if you think I’m wrong.

Yellow Book USA Inc. v. Brandeberry, No. 3:10-CV-025 (S.D. Ohio May 3, 2011).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.