Nahshin v. Product Source International, LLC is a fairly routine manufacturer-distributor dispute with a twist — a middleman. It could have mucked things up a bit, but the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board handled it neatly.

Israeli businessman and petitioner Leonid Nahshin adopted the mark NIC-OUT at least as early as January 1, 2002 outside the United States. The mark is for a cigarette filter. Two months later he entered into an agreement with non-party Nicholas Maslov to market and sell the product in the United States. Registrant-respondent Product Source International contracted with Maslov for the goods starting in 2003.

Although the Board didn’t rely on the information for its decision, Nahshin filed an application to register NIC-OUT in 2003, but the application was refused (for reasons unrelated to this cancellation) and abandoned in 2004.

Product Source filed the involved application on March 21, 2006. A few months later, Nahshin contacted Product Source and in August, 2007 Product Source started sourcing the product directly from Nahshin. Product Source’s application registered; a couple of years later Nahshin petitioned to cancel the registration.

The Board deals with it in fairly simple fashion: it started with the proposition that Nahshin originally owned the mark:

Petitioner has shown that he adopted the trademark NIC-OUT at least as early as January 1, 2002, when he entered into an agreement for the production of NIC-OUT cigarette filters. Two months later, petitioner entered into an agreement with Nicholas Maslov to market and sell petitioner’s NIC- OUT product in North America. Mr. Maslov promoted and distributed said product in the United States from 2002 through 2008.

There is no evidence that petitioner ever agreed that Mr. Maslov would own the mark in the United States or that petitioner ever assigned his rights in the mark to Mr. Maslov. Accordingly, through the distribution of NIC-OUT filters in the United States by Mr. Maslov, petitioner became the owner of trademark rights in the mark NIC-OUT in the United States; Mr. Maslov did not.

Although Product Source filed an application to register the mark, there was no evidence that Maslov authorized Product Source to do so or that any of the agreements between Maslov and Product Source transferred the mark between them or that Maslov had any rights to transfer. And as between Product Source and Nahshin, the mere distribution of a foreign manufacturer’s branded product does not give the distributor ownership interest and there was no evidence that Nahshin transferred any rights to Product Source. Nahshin therefore remains the owner of the mark. Laches and acquiescence defenses failed.

I initially had some sympathy for Product Source — Product Source said that it didn’t know where Maslov was getting the product or knew of Nahshin before it filed its application. Its relationship with Maslov was also fairly casual, so I could see some ambiguity about who owned what and that Product Source could have a good faith belief that it owned the mark.

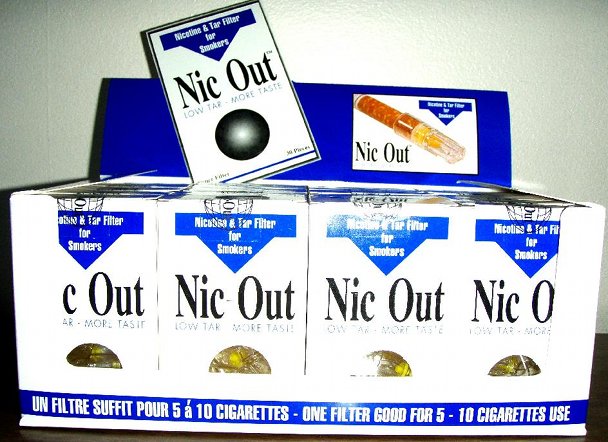

But then I looked at the specimens, Nahshin’s (top), filed in January of 2003, shortly after Product Source started buying the goods from Maslov, and Product Source’s (bottom), filed three years later:

Given the similarity of the specimens, there isn’t really any doubt that Product Source was simply reselling what it first bought from Maslov and later from Nahshin. Not mentioned in the case, Maslov had also tried, unsuccessfully, to register the NIC-OUT mark. Three applicants, all for the same trademark.

There was no suggestion in the case of any wrongdoing on any attorney’s part, but the situation made me curious. As the attorney, what is your duty to inquire into the circumstances of the manufacture of the client’s goods? If a client comes to you and asks you to register a mark for specific goods and provides a specimen, do you ask who made the goods? Who spec’ed the goods? Whether your client was giving “the benefit of his reputation or of his name and business style” to goods that another entity manufactured? And if you later learned that the client is buying exactly the same goods but from a new source, having cut out a middleman, do you ask then? What do you do about the pending application?

Nahshin v. Product Source International, LLC, Opp. No. 92051140 (TTAB June 21, 2013).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Leave a Reply