By now you’ve probably heard that Gary Friedrich’s claim of ownership of the copyright in the “Ghost Rider” Marvel Comics character has been given a second life. While the district court held that his copyright was assigned to Marvel Comics, the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed. It’s a decision that keeps on giving for a blogger on ownership issues: the decision covers three different legal theories. I’ll talk about them in a different order than the court did though, because I’ll go through the events chronologically.

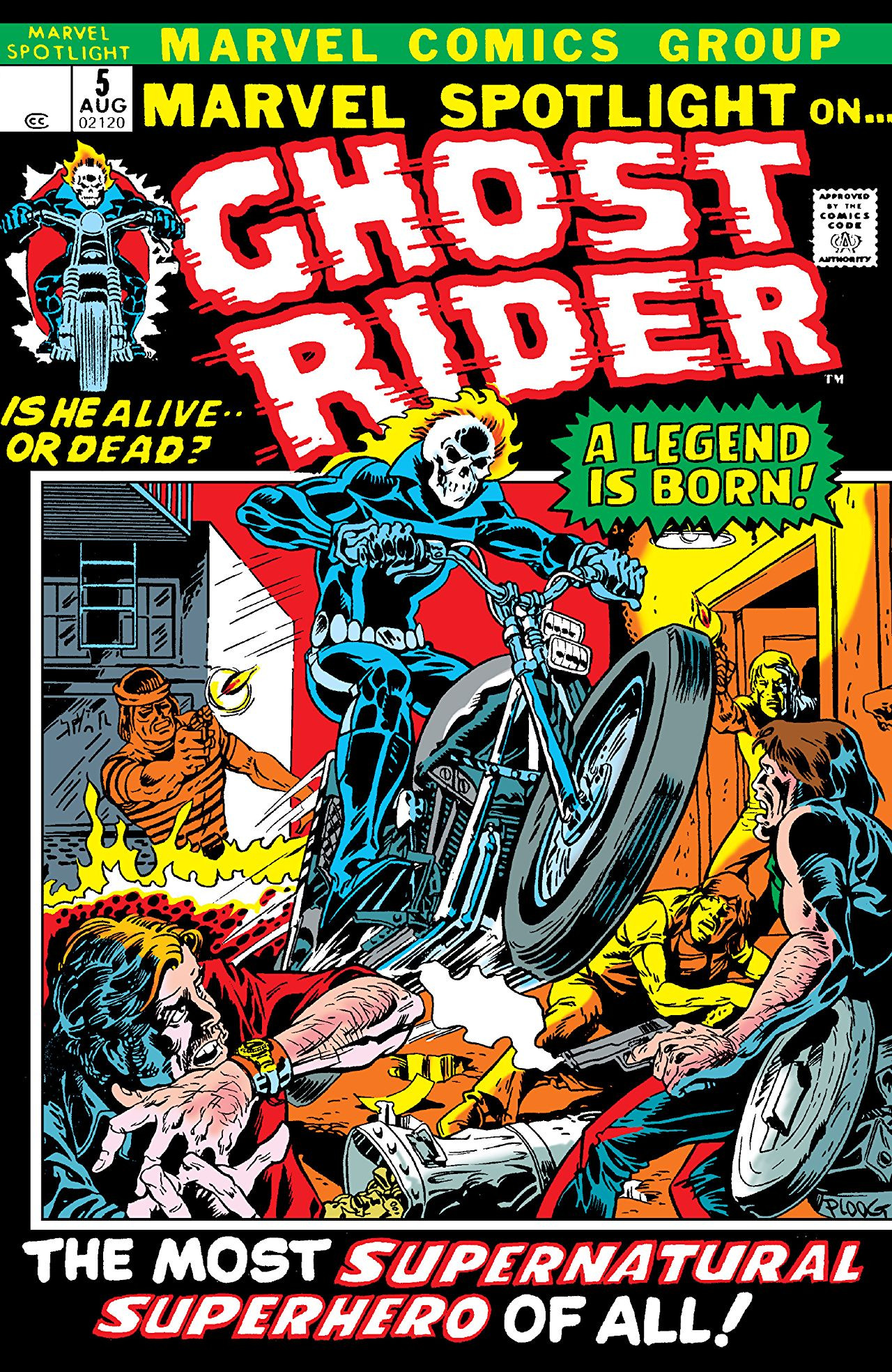

It’s a fairly simple set of facts. The case is about one work only, the original Ghost Rider comic first published in April, 1972. Gary Friedrich’s version of events is that in 1968 he created, at his own initiative and expense, a synopsis of the main characters and origin story. Friedrich was a freelancer, never employed by Marvel. Friedrich took the idea to Marvel, which ultimately published the story in Marvel Spotlight, a publication used to test new superheroes. At the time the character was created copyright was divided into two terms, the original term and a renewal term. There is no dispute that Friedrich assigned his copyright in the first term to Marvel Comics verbally, as was permitted by the Copyright Act of 1909.

The district court granted Marvel summary judgment that Friedrich had also assigned the second term in an agreement Friedrich signed in 1978, six years after the original comic was published. We’ll get to that in a minute, but first we’ll cover the status of the original work before the post-publication document was signed.

The first question is in whom the ownership of the original Ghost Rider work vested. Marvel said it was a work made for hire; Friedrich said he was the sole owner or at least a joint owner. If the work was a work made for hire at the time it was created, then Marvel Comics would be the owner of the copyright and the 1978 agreement of no moment.

There is a threshold question, though, of whether Friedrich’s claim of ownership is barred by the three-year statute of limitations. 17 U.S.C. § 507(b). A claim for ownership of a copyright accrues when there has been an express repudiation of the claim.

Recall that Friedrich did not dispute that he assigned the original term of copyright. This essentially meant that exploitation of the work during the original term were not acts that necessarily repudiated Friedrich’s ownership of the copyright.

The Copyright Act of 1976, effective January 1, 1978, controls the timing and vesting of the renewal term. In the case of the 1972 Marvel Spotlight work, the end of the first term of copyright would have been 28 years after 1972, 17 U.S.C. § 304(a)(2)(A)(1), that is, ending on December 31, 2000. After that date, the copyright would go into the 67 year renewal term, for purposes of discussion we’ll assuming vesting in Friedrich. 17 U.S.C. § 304(a)(2)(C)(i).

The court looked at public repudiation, private repudiation and implied repudiation. Publicly, Marvel repeatedly acknowledged Friedrich created the work, printing in 2005 the statement “Conceived & Written, Gary Friedrich” in its republication of the Ghost Rider issue of Marvel Spotlight. Marvel didn’t register the copyright in Marvel Spotlight until after the suit was filed, so no repudiation there. And, although the copyright notice on the comic didn’t mention Friedrich, the notice was consistent with Marvel’s ownership of the initial term of copyright, so there was no reason to believe that the notice indicated repudiation. As to private repudiation, the only undisputed evidence that Marvel did not consider Friedrich the copyright owner was in a letter to Friedrich dated April 16, 2004. The suit was filed April 4, 2007, so the claim was timely made after this repudiation.

As to implied repudiation, the Ghost Rider character wasn’t used much between 2000 and the letter in 2004 — six issues between August 2001 and January 2002; advertising a single toy in a toy catalog for two years, and a cameo appearance of Ghost Rider in a Spiderman video game. There wasn’t enough evidence to show that a reasonably diligent person would have been put on notice that there was exploitation of the copyright after the end of the renewal original term. Marvel claimed that there was a lot of publicity after 2000 about the upcoming Ghost Rider movie (filming in 2005 with a 2007 release), but the movie deal was made in 2000 when Marvel still had rights to the character. Since the practice in the industry is to pay royalties after release, the publicity alone was not enough to put Friedrich on notice that he wasn’t going to get any money. Further, in 2005 Marvel had paid Friedrich royalties on a Spotlight reprint, so a jury could find that a reasonably diligent person would not have known that Marvel claimed to be the copyright owner. The ownership claim was therefore not untimely as a matter of law.

Moving on to in whom the original ownership of the Ghost Rider character vested, under the Copyright Act of 1909 a work created at the “instance and expense” of the hiring party was a work made for hire owned by the hiring party. While Friedrich claimed to have created a synopsis with the major characters and origin story, there was contradictory evidence that all that he might have brought to Marvel Comics was an uncopyrightable idea for the character. There was evidence that others were substantially involved in the creation of the character, including a competing theory about who thought of the idea of a flaming skull for a head. So while Friedrich indeed was one of the contributors to the finished product, his contribution may have been after he started working with Marvel, performed at the instance and expense of Marvel, and therefore owned by Marvel. Thus since there is a question of fact about what Friedrich had before he started working with Marvel, the appeals court affirmed the district court’s denial of summary judgment on the ownership of the copyright in the character.

Finally we reach the major focus of the decision — assuming that Friedrich was the owner, whether Friedrich assigned the renewal term to Marvel. Marvel claimed that an agreement Friedrich signed in August, 1978 assigned the renewal term. The district court agreed, but the appeals court didn’t.

After the copyright law changed in 1978, for Marvel to continue to own the copyright in collaboratively-created comics it would need a written agreement with the contributors. It therefore had its freelancers execute an agreement for that purpose. It was this agreement that Marvel said also transferred the renewal term in Friedrich’s work to it.

The one-page agreement had one sentence that Marvel said did the trick:

SUPPLIER acknowledges, agrees and confirms that any and all work, writing, art work material or services (the “Work”) which have been or are in the future created, prepared or performed by SUPPLIER for the Marvel Comics Group have been and will be specially ordered or commissioned for use as a contribution to a collective work and that as such Work was and is expressly agreed to be considered a work made for hire.

There is a “strong presumption against the conveyance of renewal rights” which may be rebutted by express words stating a clear intention to convey the renewal. Construing the contract under New York law, there wasn’t any clear express statement here.

It is ambiguous whether the agreement covered a work published six years earlier. The document as a whole was forward-looking, and the reference to past works might have been a reference to works-in-progress. There was also no specific reference to renewal rights and instead the agreement language tracks only the 1976 Act’s definition of work made for hire.

Extrinsic evidence was of no help either; according to Friedrich he was told the agreement was for future work, not preexisting work. And here’s a lesson we’ve talked about in the past: calling a work a work-made-for-hire doesn’t make it so:

Even if the parties intended the definition of “Work” to extend to Ghost Rider, that alone would not mean that they intended the Agreement to convey Friedrich’s remaining renewal rights in that work. First, the Agreement appears to create an “employee for hire” relationship, but the Agreement could not render Ghost Rider a “work made for hire” ex post facto, even if the extrinsic evidence shows the parties had the intent to do so. The 1909 Act governs whether works created and published before January 1, 1978 are “works made for hire,” and that Act requires us to look to agency law and the actual relationship between the parties, rather than the language of their agreements, in determining the authorship of the work. Thus, regardless of the parties’ intent in 1978, the evidence must prove Ghost Rider was actually a “work made for hire” at the time of its creation. But the circumstances surrounding the creation of the work are genuinely in dispute.

I think it’s pretty clear that Marvel is using a document ill-suited to the purpose for claiming an assignment of the renewal right (and kudos for pulling it off in the district court). But Marvel has been pretty successful in the past winning the claim that the pre-1978 comics were works made for hire and I expect it will be equally successful here, despite the loss on summary judgment.

Gary Friedrich Enter., LLC v. Marvel Characters, Inc., No. 12-893-cv (2d Cir. June 11, 2013).

Correction on June 19, 2013.

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Leave a Reply