John Welch recently blogged about a case in the Southern District of New York where a trademark registration was cancelled for fraud. The case has an interesting twist, because the fundamental question really was: who owns a pen name?

John Welch recently blogged about a case in the Southern District of New York where a trademark registration was cancelled for fraud. The case has an interesting twist, because the fundamental question really was: who owns a pen name?

Plaintiff Melodrama Publishing, LLC and defendant Danielle Santiago entered into two contracts for Santiago to write the first two novels about the character “Cartier Cartel.” The novels were to be written under the pen name “Nisa Santiago” and it doesn’t appear that either party used the name before. Santiago only partially completed the novels, the contracts were terminated, and Santiago paid back the advance. Melodrama went ahead with the books with a different ghost writer, ultimately publishing five books under the author’s name “Nisa Santiago.”

In 2011 Santiago sued Melodrama for copyright infringement but the complaint was dismissed. The day Melodrama filed its motion to dismiss, Santiago filed an application to register the trademark “Nisa Santiago.” (I’m attributing actions here to Santiago, however the acts were actually performed by her lawyer. The court couldn’t figure out who the decisionmaker was, Santiago or her lawyer.) She used the Melodrama book covers for books she did not write as the specimens proving her use of the trademark. She then threatened Melodrama with trademark infringement. Melodrama filed a declaratory judgment action against Santiago.

That Santiago didn’t have trademark rights in “Nisa Santiago” was a slam-dunk, since she admitted in her answer that she never used the mark in commerce. You be the judge whether there was fraud; as we know, lay people and non-trademark lawyers don’t understand the legal standards for things like “use in commerce.” So decide for yourselves whether the behavior crossed the line from naive to fraudulent. And feel free to discuss below.

So the court didn’t have to decide who owned the pen name “Nisa Santiago,” only the trademark. When reading the case I assumed that the publisher would own the name — certainly in the case of serial potboilers the publisher will want to use the same pen name for all authors.

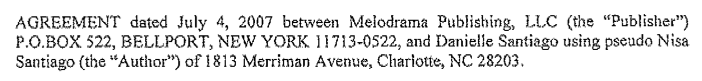

But the contracts tell a different story. First, we have the introductory paragraph:

It says “… Danielle Santiago using pseudo [sic] Nisa Santiago (the “Author”) …” Thus, the contract defines “Nisa Santiago” as the pseudonym for Santiago, not the name under which the book will be published. This ownership is ratified later:

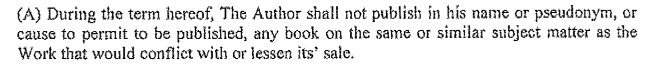

“… The Author shall not publish in his [sic] name or pseudonym … any book of the same or similar subject matter …” The contract continues:

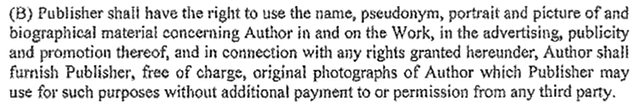

“Publisher shall have the right to use the name, pseudonym, portrait and picture of and biographical material concerning Author in and on the work …”

Ah, acknowledgement that Melodrama needs permission to use the pseudonym and a place for Santiago to hang her hat — the contract was terminated, thus Melodrama no longer had the right to use Santiago’s pseudonym.

So we have a theory, but it’s a contract theory, not a trademark theory. And under a contract theory, there’s no case for damages. Santiago hadn’t used the name before, so it had no value before it was used by Melodrama. De minimis non curat lex.

But more interesting to me, shouldn’t a publisher have this buttoned up better? When hiring an author to write a series of books under a pen name, isn’t it fairly foreseeable that the ghostwriter might change but the “author’s” name should remain the same? This case would have been very different if Santiago had published the first two books as originally contemplated, because then the hold-up would have worked. Santiago would have had use of the mark and a contract backing up that she, not Melodrama, was the owner. Is this how these contracts are normally written?

Melodrama Publishing, LLC v. Santiago, No. 12 Civ. 7830 (JSR) (S.D.N.Y. April 10, 2013).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Leave a Reply