I confess that I haven’t paid enough attention to Aalmuhammed v. Lee, 202 F.3d 1227 (9th Cir. 2000) and its direction on the issue of “authorship” in a joint work. In Aalmuhammed, the Ninth Circuit observed that not everyone who contributes to a work is an author and set out, in the context of a contribution to a motion picture, how to determine whether someone was an author:

| First, an author “superintend[s]” the work by exercising control. This will likely be a person “who has actually formed the picture by putting the persons in position, and arranging the place where the people are to be – the man who is the effective cause of that,” or “the inventive or master mind” who “creates, or gives effect to the idea.” Second, putative coauthors make objective manifestations of a shared intent to be coauthors, as by denoting the authorship of The Pirates of Penzance as “Gilbert and Sullivan.” We say objective manifestations because, were the mutual intent to be determined by subjective intent, it could become an instrument of fraud, were one coauthor to hide from the other an intention to take sole credit for the work. Third, the audience appeal of the work turns on both contributions and “the share of each in its success cannot be appraised.” Control in many cases will be the most important factor. |

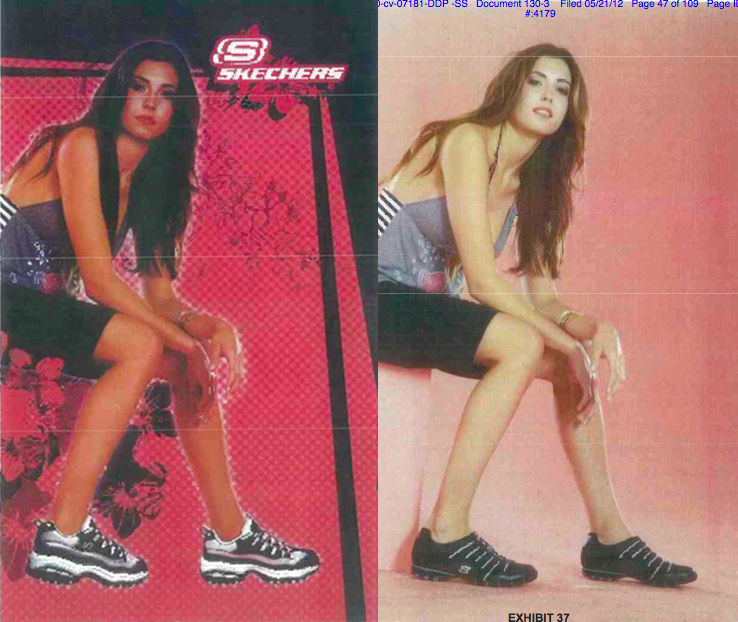

In Reinsdorf v. Skechers U.S.A., the court considered the question in the context of advertising material. Richard Reinsdorf took photos that were to be used in advertising for the shoe company Skechers. His photos were only raw images; Skechers took the images and altered them for the advertisements. You can see the types of changes made below, with the ad on the left and a similar raw photo on the right:

|

| (click on image for larger version) |

Reinsdorf invoiced Skechers for the photos. He later alleged that Skechers exceeded the temporal and geographic scope of the license that he granted.

Skechers’ defended that the advertisements were a joint work of authorship and therefore, as a joint author, it could do what it liked with the photos. Reinsdorf sought to disavow that he was a joint author of the finished works.

According to the statute and case law, in the Ninth Circuit a work of joint authorship is prepared by two or more authors who make independently copyrightable contributions and intend for those contributions to be merged into inseparable or interdependent parts of a unitary whole. 17 U.S.C. § 101; Ashton-Tate Corp. v. Ross, 916 F.2d 516, 521 (9th Cir. 1990). But this begs the question — when is one an “author”?

Which is what takes us to Aalmuhammed and its three factors, as described by the Reinsdorf court: 1) an alleged author exercises control over a work, serves as the inventive or master mind, or creates or gives effect to an idea; 2) there exists an objective manifestation of a shared intent to be coauthors; and 3) the audience appeal turns on both contributions and the share of each in its success cannot be appraised.

With respect to control, there can be joint control when both parties have creative control over separate and indispensable elements of the completed product. That was the case here; Reinsdorf had control over the raw photos and Skechers over the graphic design. This weighed in favor of joint authorship.

With respect to audience appeal, there was no evidence that the success was attributable to one or the other, so this factor weighed in favor of joint authorship.

Which leaves us with the objective manifestation of the parties’ intent on joint authorship. Here, the court distinguished the parties’ intent that their work be merged into a unified whole from the intent that they be joint authors:

| Aalmuhammed itself provides a useful illustration of the distinction. There, the plaintiff wrote certain passages and scenes that appeared in a movie. The court found that the parties all intended for the plaintiff’s contributions to be merged into independent parts of the movie as a whole. That intent, however, had no bearing on whether the parties intended the contributing plaintiff to be an “author” of the film. Applying the control, audience appeal, and intent factors described above, the Aalmuhammed court ultimately determined that, despite the parties’ intent to merge their independent contributions, the parties did not intend for the plaintiff to be a co-author of the movie and the plaintiff was not an author of the film. |

So although Skechers showed that Reinsdorf intended that his work become part of a unified whole, that wasn’t enough. And what hurt Skechers the most? Paying Reinsdorf:

| Indeed, the parties behaved in ways uncharacteristic of joint authors. Perhaps most importantly, Reinsdorf charged Skechers thousands of dollars for his work. Not only did Reinsdorf charge for his time and effort, but also for “usage” of the photographs. Reinsdorf also attempted to limit Skechers’ use of its ads by including temporally and geographically restrictive language in his invoices to Skechers. Skechers, for its part, also sought to prevent Reinsdorf from making use of the finished images on his personal website, even during the pendency of this suit.A party intending to jointly produce a finished work generally would not require payment from a co-author and, conversely, would not likely agree to pay for a purported co-author’s contribution. More importantly, a co-author would not attempt to constrain an intended co-author’s use of a collaborative work. Other courts have come to similar conclusions under similar circumstances. In Tang v. Putruss, 521 F. Supp. 2d 600 (E.D. Mich. 2007), for example, a contract between a photographer and a purported coauthor required that the second party pay the photographer money before using the photographer’s photos. Id. at 607. The court found such a provision inconsistent with an intent to be joint authors. Id.

The court in Robinson v. Buy-Rite Jewelry, Inc., No. 03 CIV 3619(DC), 2004 WL 1878781 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 23, 2004), addressed circumstances similar to, but critically different from, those here. In Robinson, as here, a photographer was hired for a fashion shoot, and yielded all subsequent decision-making authority as to how the photos would be used. Id. at *3. Unlike here, however, the photographer agreed that the other contracting party could use the photographs without limitation. Id. Relying on this “critical” fact, the court concluded that the parties did intend to be joint authors. Id. |

Huh. I don’t think I buy that as a general rule, or even necessarily good evidence. There are many reasons why one joint author would pay another, even a fixed amount. Because one author wanted to be compensated at the beginning of a project and not wait for a royalty stream. Because, as in this case, the value of the contribution cannot be tied to revenue because the work isn’t directly revenue-producing. Because one doesn’t want to take any risk on future income.

The court concluded that a factfinder could find that there was an absence of intent to be joint authors of the finished work and summary judgment was therefore denied.

I also wonder about Skechers’ desire that Reinsdorf be a joint author, which means that Skechers’ has a duty of accounting to Reinsdorf. Reinsdorf did a survey purportedly designed to test whether the photographs influenced consumers’ decision to purchase a product and offered expert testimony to establish the amount of Skechers’ profits attributable to Skecher’s use of Reinsdorf’s photographs. But the court threw out the expert report: “Turner’s entire contribution to the dispute essentially amounts to ‘I have a lot of experience with brands and marketing, therefore I can divine that 50%-75% of this large successful, company’s profits come from Reinsdorf’s photographs.’ … Turner somehow settles upon an indirect profits figure between $161 million and $241.1 million without any specific data or discernible methodology ….’” A second, more moderate (only $33 million), expert report was also thrown out as untimely, and it suffered from methodological flaws too. Therefore Skechers’ motion for summary judgment on an indirect profit claims was granted and, since Reinsdorf hadn’t timely registered the copyright in the photos, Skechers motion on statutory damages and attorney’s fees was also granted.

So Skechers lucked out on the joint authorship route here and its exposure is limited to Reinsdorf direct damages, i.e., the licensing fee for the photos. But still, in an advertising case, a joint authorship theory puts your product profits at risk. Bold move.

Reinsdorf v. Skechers U.S.A., No. CV 10-07181 DDP (SSx) (C.D. Calif. Feb. 6, 2013).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Leave a Reply