Ok, I’m very confused by the decision in the TTAB case O.T.H. Enterprises, Inc. v. Vasquez. What’s confusing is that the Board discusses, in two separate parts of the decision, ownership of the mark and priority. I don’t really get that – if the case is about who owns the mark, what other mark is there to compare it to for purposes of priority?

The decision alludes a number of times to a lack of clarity in the briefing, so I suspect the Board was ensuring that it was responsive to all theories raised. But I’ll consider them just two different theories of ownership, one based on assessing who controls the mark and the other a chain of title analysis. Here goes.

The opinion is on a petition to cancel the mark for a band’s name, GRUPO PEGASSO, registered in 2005 for sound recordings in Class 9 and and live performances in Class 41. The decision starts with the cast of characters, which I’ll distill down:

The opinion is on a petition to cancel the mark for a band’s name, GRUPO PEGASSO, registered in 2005 for sound recordings in Class 9 and and live performances in Class 41. The decision starts with the cast of characters, which I’ll distill down:

Vasquez: Registrant and claims to have started the band in 1979.

Reyna: Non-party; member of the band from 1981-85, then left the band and performed and recorded as Grupo Pegasso and Pega Pega de Emilio Reyna. Also registered GRUPO PEGASSO in 1995 but the registration was cancelled in 2002 for failure to file a Section 8 affidavit.

Benavides: Non-party; sound engineer and manager for the band from 1981 until his death in 1989 and principal of the recording company Discos Remo.

The Board first considered who owned the band name GRUPO PEGASSO. Relying on McCarthy, it applied the following test for ownership of the name of a performing group:

| (1) whether the group name is personal to the members; (2) if the name is not personal to the members, for what quality or characteristic is the group known; and (3) who controls that quality? |

Here, there was apparently no argument that the name was not personal to the members, so the Board looked at the qualities and characteristics for which the group was known and who controlled them. O.T.H. claimed that Benavides, as the manager and its predecessor-in-interest, controlled the band from 1985 until his death in 1989. However, the only admissible evidence that O.T.H. had was Benavides’ filing of an assumed business name. But a business name isn’t evidence of trademark use because it is not evidence of a person’s right to exclude others from using a mark, nor does it provide evidence of control over the quality of the music group. A further flaw in the theory was that the band put out five albums between 1979 and 1985, making it “difficult for us to accept” O.T.H.’s allegations of ownership without addressing the period from 1979-1985 and how Benevides would have succeeded to ownership in 1985.

O.T.H. argued alternatively that Reyna owned the mark from 1981 to the present, or 1989 to the present, but the only admissible evidence was a partial file wrapper for his registration. But there was no evidence of Reyna’s control over “the GRUPO PEGASSO mark” (I think the Board means the goods or service with which the mark is used), and therefore no evidence that Reyna was owner of the mark.

On the other hand, Vasquez testified that he started the band in 1979 and was the only member who was in the band during its entire existence. He testified that he named the band after a local rotary club and designed the logo. Another former band member testified that Vasquez acted as director and guided the band by instructing them how to play certain arrangements. The witness’s testimony corroborated a statement on the back of an album stating that “[Vasquez], director, arrangement, guitarist of the group, he always adds that special flavor to the melodies that they perform and a great deal of that is what gives the Grupo Pegasso so much success.” (I’m not sure why the album back isn’t hearsay, but whatever). Vasquez also owned Mexican trademark registrations, his son testified to the father’s control of the band, and Vasquez informed a Music Worker’s Union in Mexico of new band members so that Grupo Pegasso could “keep working” and “comply with its pending contracts.”

Thus, Vasquez is the owner of the GRUPO PEGASSO mark,* and both parties conceded that there was likelihood of confusion. I would have thought that was the end of the decision – but wait, for some reason the Board goes on to talk about “priority.” I think it’s because Vasquez and Reyna both continued to perform, apparently for many years, as independent “Grupo Pegasso’s”: Vasquez as “[Grupo] Pegasso del Pollo Estevan” and Reyna as “Grupo Pegasso de Emilio Reyna” – but the Board didn’t really explain, and it also noted that the addition of “del Pollo Estevan” only added matter to the mark, it didn’t change the mark.

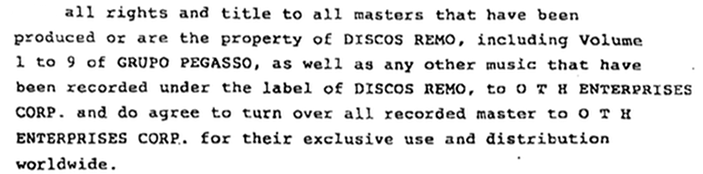

So we forge on. O.T.H. didn’t have a registration and therefore had to prove common law rights in the mark. It claimed to have acquired rights from Discos Remo, the company that produced the Grupo Pegasso albums which, you’ll recall, was owned by Benevides. Benenvides’ widow and a business partner assigned some rights to O.T.H., but the assignment had a couple of problems. First, there was no evidence about how Benevides’ widow and the business partner came to have the right to dispose of Discos Remo’s assets. Second, the assignment was of:

Note no mention of any trademark or band name, or any evidence of the entire sale of a business. A later “confirmatory assignment” for the same transaction was more explicit about assigning ownership of the copyrights, but again no mention of a trademark.

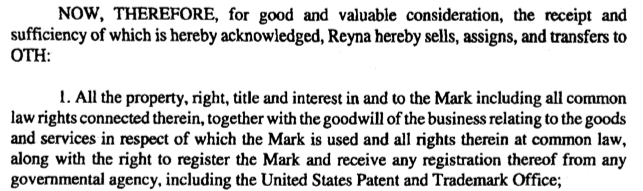

Finally, O.T.H. alternatively claimed to have obtained trademark rights from Reyna (who you will recall had a cancelled registration for the mark) by assignment:

The problem with this transaction is that Reyna couldn’t have established common law rights in the name before Vasquez did because Reyna didn’t join Vasquez’s band until after its first album and performances in the U.S. (There were some other reasons given by the Board, but the Boards seem to be holding against O.T.H. that it made arguments in the alternative, so I won’t go into them.)

So O.T.H. didn’t get the trademark by assignment either. A claim that the mark was abandoned failed on lack of proof of cessation of use (litigation tip – if you are claiming abandonment, don’t let your own witness testify that he is still currently selling albums), and a claim that the registration was procured through fraud failed on all elements. The petition to cancel the Vasquez registration was therefore denied.

O.T.H. Enterprises, Inc. v. Vasquez, Cancellation No. 92050569 (TTAB Sep. 28, 2012).

*This conclusion strikes me as what is meant by “a name being personal to the members.” That is, McCarthy distinguishes the two scenarios as “whether the service mark or name identifies and distinguishes that particular performer combination or just style and quality….” 2 McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition § 16:45 (4th ed.). The distinction is between something like the Rolling Stones, where the band wouldn’t be the Rolling Stones without particular members, and a producer-created concept group like Menudo, where the members frequently changed because they no longer fit the concept (too adult, in the case of Menudo). In this case, it seems to me that the band name is personal to one of the members, Vasquez. But if nothing else, this case demonstrates that the doctrinal framework for band names isn’t particularly helpful.

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Leave a Reply