It’s common in many industries for a company to be named after its partners. The names both individually and as part of the firm name develop goodwill, which makes it a challenge when an individual departs – how do you divvy it up? Not how it was done in Basile Baumann Prost Cole & Assocs., Inc. v. BBP & Assocs. LLC.

Basile Baumann Prost Cole & Associates, Inc. was an economics and real estate consulting firm. It was originally established in 1990 as Basile Baumann Prost & Associates, Inc. The firm used the acronym “BBPA” and had the domain name “bbpa.com” for its website. Basile and Prost mostly did work for state and local governments and Baumann mostly did Navy work. In 2006 Baumann sold his share of the company to Cole, the name was changed to add “Cole,” and the company started using “BBPC”:

However, it continued to have its website at “bbpa.com.”

Cole continued to do the Navy work. About three years later, Basile and Prost decided they didn’t want to work with Cole anymore and they entered into a Stock Redemption Agreement to cash out. In the Stock Redemption Agreement, Basile and Prost got to keep

If you can’t read it, it says “[a]ll goodwill created on all past contracts and clients by Basile and Prost [within the last four years] to include but not be limited to any and all use of job qualifications and materials and job references for Basile and Prost’s contracts and clients.” The corporation retained all assets not assigned, which included the “Basile Baumann Prost Cole & Associates” name.

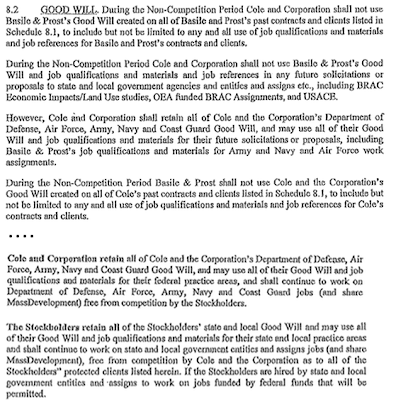

There was also an addendum on “goodwill” that describing how the parties could use the other’s “goodwill” in certain fields, e.g., Cole could use Basile’s and Prost’s goodwill for military contracts:

Before moving on to the decision, can we talk about how awful this concept is? What on earth does “goodwill” mean here? It appears that the parties were trying to define how they could refer to work done during the relationship. Undoubtedly how the two companies distinguish their businesses while still taking credit for their previous work is going to be the trickiest area for the two companies to navigate in the future. But leaving this difficult task to the undefined and ambiguous term “goodwill” – a term that those of us who work with it every day are still challenged to define – almost guaranteed a lawsuit.

Basile and Prost’s new business was “BBP & Associates” (note that there weren’t two “B’s” working for the business, just Basile) and used the below logo:

BBP & Associates then claimed in various ways, extensively documented in the opinion, that it was a successor to Basile Baumann Prost Cole & Associates, including rewriting testimonials given to the original company to put in the BBP & Associates’ name and listing awards given to the original company. Not unexpectedly this caused confusion for Cole’s business, including checks sent to the wrong place (never a good thing for a trademark infringement defendant). Basile Baumann Prost Cole & Associates complained; BBP & Associates changed its logo:

Ultimately Basile Baumann Prost Cole & Associates sued BBP & Associates for trademark infringement, cybersquatting, false advertising and related state law claims. Both parties filed motions for summary judgment and indeed what “goodwill” means was one of the sticking points.

BBP & Associates defended against the charge by claiming that Basile Baumann Prost Cole & Associates transferred “most or all of the goodwill associated with [marks such a ‘BBP’ and “BBP LLC’]” under the Stock Redemption Agreement. Basile Baumann Prost Cole & Associates claimed that it transferred only the personal goodwill of Basile and Prost but had retained the corporate goodwill. Here’s the court’s primer on “goodwill”:

| Goodwill is “the total of all the imponderable qualities that attract customers to [a] business.” “There may be business or professional goodwill, or both combined in one enterprise.” Professional, or personal goodwill, “is good will that is based on the personal attributes of the individual such as personal skill, training, or reputation.” In Maryland, the concept of personal goodwill most often arises in cases involving the distribution of property in divorce, or covenants not to compete.

“If … consumer satisfaction and preference is labeled ‘good will,’ then a trademark is the symbol by which the world can identify that good will.” “A sale of a business and of its good will carries with it the sale of the trademark used in connection with the business, although not expressly mentioned in the instrument of sale.” |

[Footnotes and citations omitted.]

The court agreed with Basile Baumann Prost Cole & Associates that the Stock Redemption Agreement was not a sale of a business that impliedly transferred the trademarks to Basile and Prost:

| The Stock Redemption Agreement is unambiguous in at least one respect: it was not a sale of the Corporation’s entire business and goodwill. Although Basile and Prost acquired certain assets—including 83 jobs, 138 leads and proposals, and the “goodwill [they] created on [certain] past contracts and clients”—the Corporation retained all other assets, including the company name and location, two-thirds of the staff, and 70 percent of the Corporation’s contracts by revenue. Thus, the agreement was not a “sale of a business and … its good will” that impliedly transferred the Corporation’s trademarks. |

Basile and Prost also argued that Basile Baumann Prost Cole & Associates had abandoned the mark “BBPA” but they did not meet their burden of proof for summary judgment. They also failed to prove, on summary judgment, that there was no likelihood of confusion. But it wasn’t so one-sided that Basile Baumann Prost Cole & Associates proved that there was confusion, and summary judgment in its favor was denied also.

This is what happens when you don’t have trademark lawyers working M&A.

Basile Baumann Prost Cole & Assocs., Inc. v. BBP & Assocs. LLC, Civ. No. WDQ-11-2478 (D. Md. June 19, 2012).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.