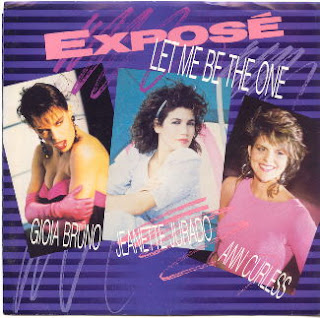

We’re talking about an unregistered trademark here, for the band Exposé. (There was an early effort to register the mark but it was unsuccessful.) A company called Pantera Productions, Inc. started the band in 1984 with three women but the band wasn’t a success. In 1986 Patera then replaced the original members with three defendants in this case, Jeanette Jurado, Anne Curless and Gioia Bruno. Jurado, Curless and Bruno’s faces and names were on album covers.

They were considerably more successful than the original trio; the band’s debut album went triple platinum and they had a number of other successful records. At one point Bruno had to leave due to illness and was replaced by Kelly Moneymaker. The band disbanded in 1995 and Jurado, Curless, Bruno and Moneymaker signed an agreement with Pantera absolving them of obligations they had to Pantera, stating that Pantera had conceived of and owned the Exposé mark, and that the singers would no longer have any right to use the mark.

In 2003, Jurado and Curless signed a trademark license agreement with Crystal Entertainment, Pantera’s successor, because they wanted to start performing again as Exposé. In the agreement, they again acknowledged that Crystal Entertainment owned the Exposé mark. Due to Curless’ pregnancy, though, they only performed once and cancelled the rest of the tour.

In 2006, Jurado, Curless and Bruno executed another trademark license agreement with Crystal Entertainment in anticipation of a tour. In the agreement, the three acknowledged that Crystal owned and controlled the Exposé mark.

The three went on tour, managing their own tour schedule and promotion. In 2007, the women’s production company filed an application to register the Exposé mark. Their lawyer sent a letter to Crystal Entertainment disputing Crystal Entertainment’s ownership of the mark and the band stopped paying royalties to Crystal Entertainment because of its lack of participation in the band’s promotion and marketing.

Crystal Entertainment took a mulligan on a first complaint filed in 2007 and sued again in 2008, claiming breach of the 2006 agreement, trademark infringement, cybersquatting, and unfair trade practices under Florida law. In a bench trial, the district court held in the defendants’ favor on all claims except breach of the 2006 contract, awarding $25,060 to Crystal Entertainment on the claim. Crystal Entertainment appealed.

The issue boils down simply to who owns the Exposé mark. First up was whether Crystal Entertainment had established trademark rights with the first iteration of the band:

| We have applied a two-part test to determine whether a party has proved prior use of a mark sufficient to establish ownership: Evidence showing, first, adoption, and, second, use in a way sufficiently public to identify or distinguish the marked goods in an appropriate segment of the public mind as those of the adopter of the mark. The district court was required to inquire into the totality of the circumstances surrounding the prior use of the mark to determine whether such an association or notice was present. We have determined that a company proved prior use of a mark sufficient to establish ownership when, among other things, the distribution of the mark was widespread because the mark was accessible to anyone with access to the Internet, the evidence established that members of the targeted public actually associated the mark … with the product to which it was affixed, the mark served to identify the source of the product, and other potential users of the mark had notice that the mark was in use in connection with the product. |

(all sorts of quotation, citation and bracket crap removed.) The court held that the original trio’s use of the Exposé mark wasn’t sufficiently public to establish trademark rights in the mark, largely because the district court didn’t believe the testimony.

Thus, “Because Crystal failed to prove that it first appropriated the Exposé mark, the district court was required to determine the owner of the mark where prior ownership by one of several claimants cannot be established.” Following Bell v. Streetwise Records, Ltd., 640 F.Supp. 575 (D. Mass. 1986):

| To determine ownership in a case of this kind, a court must first identify that quality or characteristic for which the group is known by the public. It then may proceed to the second step of the ownership inquiry, namely, who controls that quality or characteristic. |

Under this standard, it was a slam dunk for the band members:

| The district court found that Crystal failed to prove that it had selected Moneymaker, had exercised control over Jurado, Curless, and Bruno, or had taken any active role in scheduling any of the group’s performances; Garcia [of Pantera] had conceded that he had been unable to put a different group together to perform as Exposé since 1986; the involvement of Crystal with Exposé was limited to collecting royalties from the sale of records; and the private agreements upon which Crystal relied disclosed nothing to the public to change this perception. The district court also found that Exposé had been consistently portrayed to the public as Jurado, Curless, and Bruno since 1986; they were the product denoted by the Exposé mark; they owned the goodwill associated with the mark; and a member of the public who purchased a ticket to an Exposé concert would clearly expect to see Jurado, Curless, and Bruno perform. |

But what about the THREE agreements where the women agreed that Pantera and its successor Crystal Entertainment were the owners of the mark? Notably, in Bell v. Streetwise Records there was no contract because the plaintiffs were minors at the time of the contract’s execution and they later disaffirmed it, so Bell isn’t on all fours. Here, “the private agreements upon which Crystal relied disclosed nothing to the public to change this perception.”

Wow. So apparently in the 11th Circuit a private agreement doesn’t matter; rather, the actual ownership has to be manifested publicly. I’m not saying the outcome is wrong – band names are a different world when it comes to trademark ownership, because the members are often so strongly identified with the public image of the band. But I would have liked a little more compelling reason for why the court felt that the contracts, as well as the defendants’ belief that they needed a license, could just be ignored.

Crystal Enter. & Filmworks, Inc. v. Jurado, No. 10-11837 (11th Cir. June 21, 2011).

Crystal Enter. & Filmworks, Inc. v. Jurado, Civ. No. 08-cv-60125-MGC (S.D. Fla. May 26, 2009) (trial transcript).

Crystal Enter. & Filmworks, Inc. v. Jurado, Civ. No. 07-cv-61748-WJZ (S.D. Fla.) (dismissed without prejudice).

The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

One response to “How to Steal a Trademark”

No doubt if the trademark had been established by the artists, but the management were able to prove they had done all the work in establishing their identity many lawyers would be on the side of the managers.

Score one for artists..its about time.

It’s been along time since the law was important to most corporate lawyers.