The always informative John Welch, TTABlog reporter, blogged on a pure trademark ownership contest at the TTAB in an opposition proceeding. It was a bit of a lengthy and confusing read, 41 pages, although the TTAB does bless us with generous double-spacing and Courier New.

The case is a lesson in how not to manage your manufacturing and distribution relationships. The TTABtale picks up when two entities claim to own the mark WASTEMAID for food waste disposers; one was the manufacturer and the other was the distributor. The factual background is convoluted, since neither was actually the first to use the trademark. Instead, the mark was initially adopted by a wholesaler, the manufacturer made the disposers for the wholesaler, and the distributor was the middleman. Eventually the wholesaler sold the trademark to the distributor, the distributor applied to register in the U.S., and the manufacturer opposed, claiming it was the owner of the mark.

My problem with cases of this type is that the fact finders look at it as a question of priority, but there’s only one trademark that two entities are fighting over. Cases exploring whether trademark rights exist at all may not be the best guidance when the question is, rather, who owns trademark rights both parties acknowledge exist.

Here, the TTAB roamed through several theories to find that the manufacturer did not own the mark. Somewhat surprisingly, it didn’t use the fairly well-developed law for manufacturer-distributor disputes (where, incidentally, the presumption goes to the manufacturer). Instead, it first looked at whether the opposer had used the mark in a way to establish a “trade identity” in the mark, i.e., whether it was functioning as a trademark, and decided inexplicably that because it was a “private placement” it was not.

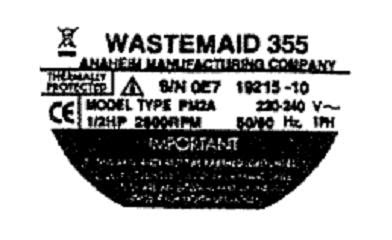

Next, the TTAB said that priority would be established by a use that was “open and notorious, reaching to prospective purchasers of the goods in which the mark is claimed for use.” The problem was that the manufacturer had; it used the mark on a label that would have satisfied the most difficult examination of a trademark specimen. There was no explanation for why this use wasn’t sufficiently “open and notorious.” Finally though, the TTAB resorted to weighing the “evidence as a whole,” numbered paragraphs and all, which indicated that the manufacturer was a private labeler, not the owner of the mark. Based on the facts recited the conclusion seems right in the end. Nevertheless, the case gives little guidance on how these disputes can be decided more predictably in other cases.

Finally though, the TTAB resorted to weighing the “evidence as a whole,” numbered paragraphs and all, which indicated that the manufacturer was a private labeler, not the owner of the mark. Based on the facts recited the conclusion seems right in the end. Nevertheless, the case gives little guidance on how these disputes can be decided more predictably in other cases.

Anaheim Mfg. Co. v. Joneca Corp., Opposition No. 91171906 (March 26, 2009).

© 2009 Pamela Chestek